Over the summer, we’ll be re-upping three previously pay-walled classic TPE columns for you to enjoy. This week, Oscar goes searching for the lost backpackers of Byron Bay, originally published February 23, 2023.

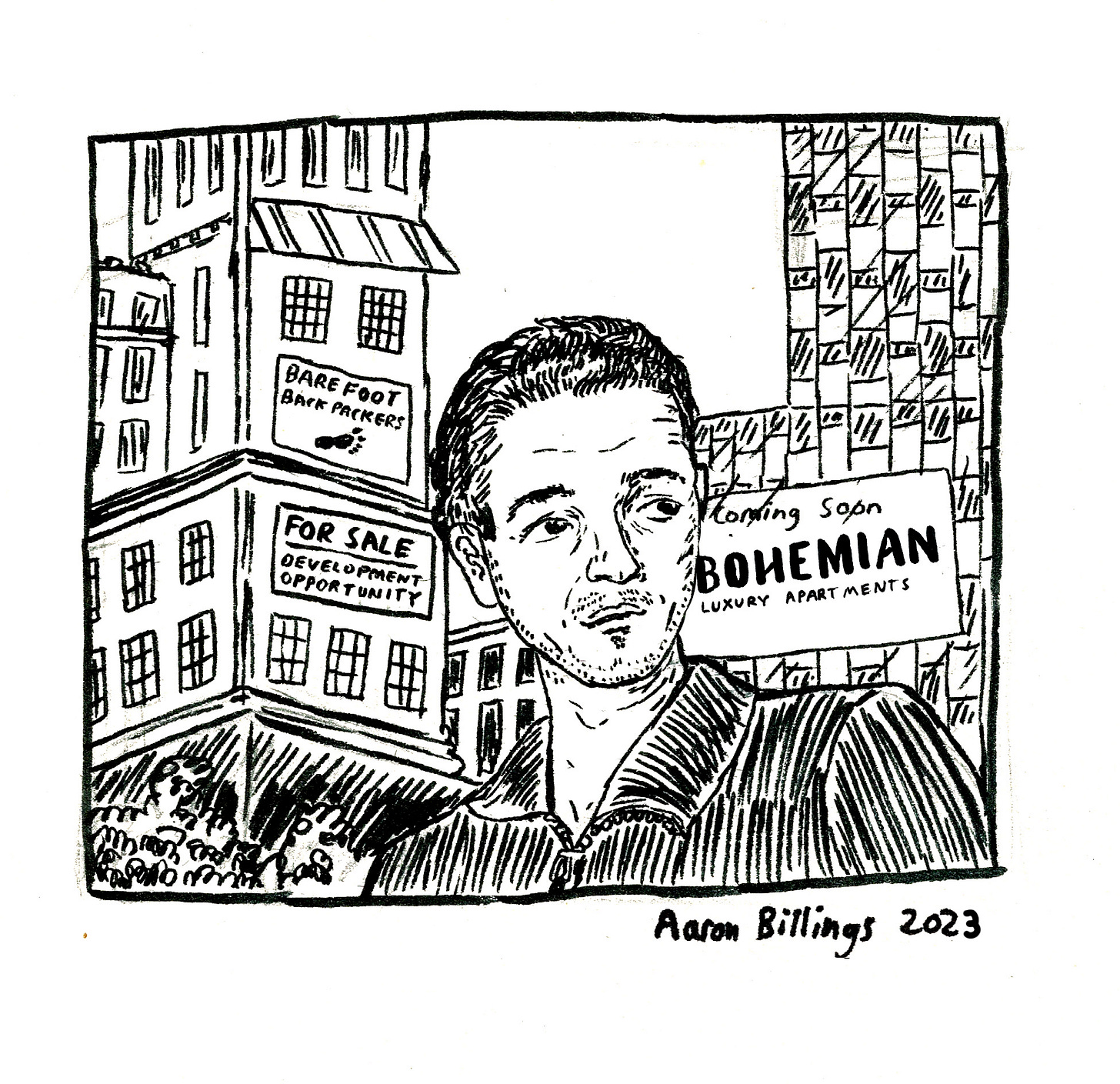

The backpacker’s hostel has disappeared. Or at least it’s not where I last saw it. Right here, next to the supermarket. I remember it well. I was seventeen and barefoot, listening to a topless French backpacker who was alternately playing the guitar and the didgeridoo. He was singing: “realise your real eyes in Byron Bay.” Now all I can see is a demolition site and a poster advertising a new luxury apartment complex called “Bohemian.” Underneath someone has scrawled: “Fuck off corpo scum! Fuck West Byron!”

I have been in Byron Bay for three days searching for backpacker life but so far not a trace. I saw no MacPacs rotating around the airport luggage conveyor belt, but sleek, hard shell Rimowa suitcases. In town, the streets were empty of busking Frenchmen and in their place sauntered well-groomed Brits wearing three-quarter length distressed jeans and white sparkling Air Force 1s. At the beach, there were no fire twirlers, but influencers working on their supernatural bodies. I did see some traveler vans down by the foreshore. I caught a glimpse of one done up like a Design Files apartment—pot plants and a gas oven and a white tiled splashback. A toned couple lay on the bed, covered in linen throws, gazing at the beach, where every morning two red diggers moved sand from one part of the shore to another, “to make it look perfect for the coming summer,” one of the workers told me.

Why am I looking for backpackers in Byron Bay? This sub-genre of person has been on my mind ever since I saw a poster for the screen adaptation of the 2003 novel, Shantaram, late last year. The poster was styled after a vintage Bollywood movie flier and it triggered a memory of when I had been in India one year out of high school on my first backpacking trip. A fellow traveler in a guesthouse somewhere in the state of Rajasthan handed me a copy of Shantaram and told me she found it “life changing.”

The book was nominally fiction, but quite obviously based on the life of the author, Gregory David Roberts, a Melbourne-born philosophy student who fell in with a bad crowd, became addicted to heroin, and robbed a few banks. (I am told he once stuck up Paperback Bookshop). He was caught, escaped Pentridge prison, fled to Bombay, and reinvented himself as a slum doctor before being recruited by a mafia boss to smuggle weapons to the Pakistani border for mujahideen freedom fighters. He was eventually caught, again, but this time he used his stint behind bars to write a book about his exploits.

It was a runaway success, one of the best-selling novels in Australian history, an instant backpacker classic—passed from traveler to traveler until it ended up in my impressionable hands somewhere in the north west of the subcontinent. The prose was verbose and rambling, yet I was impressed by the story—maybe even a little inspired. I was 19 and it was 2007. I was traveling without an iPhone. Tumblr didn’t even exist yet. I didn’t know why it was bad for white guys to have dreads. There was an intact cultural thread leading directly back to the covetously mobile Boomer backpacker generation, those who Richard Neville, founder of Oz magazine, described in his 1970 book Power Play, as “new gypsies who flow across the world; congealing in communal crash pads, caves, camping grounds, Youth Hostels.”

Gregory David Roberts—a barrel-chested man with auburn hair and a handlebar mustache—was a cartoonishly exaggerated example of this archetype. The Uber-backpacker. Part of me was still naive enough, or not yet protected by layers of irony or post-colonial theory, to be envious of his freewheeling life. But there was another part that intuited how deeply uncool Gregory David Roberts was, along with his fictional avatar, Lin Ford (or as he is called by the Bombay locals, “Linbaba”). There was something waning in the figure of the masculine voyager. He was going out of fashion.

This is why I was surprised to see the Shantaram poster on my walk to work some 15 years later. Who would want to watch a 10-part streaming series about a white guy finding himself in India now? Hadn’t the formerly aspirational identity—the Uber-backpacker—been utterly discredited? Or was the spirit of the backpacker still alive somewhere, hiding out and stubbornly resisting the Airbnb-ification of everything?

*

After visiting the demolished backpackers hostel, I call my friend Sasha, whose family has lived on and off in a stunning house overlooking a lily-covered dam just outside Mullumbimby for decades. She says that the number of backpackers around Byron has been incrementally declining for many years, but that the big break was Covid. For the first time the backpackers disappeared entirely as the town became a hideout for Hollywood expats.

“It’s impossible for backpackers in town,” she says. “The rent is too high, the hostels are too expensive, and you can’t park your van anywhere.”

Some young travelers are starting to trickle back, she says, but they are staying in smaller towns nearby, like Brunswick Heads, where there are still a few cheap motels and spots to park overnight. This has made it more difficult for residents displaced by rising rents to find temporary places to stay. “Lots of the locals have had to start camping in the nature reserves,” she says. “Pretty bleak.”

Sasha pauses and then tells me a story. Her boyfriend, Leo, was surfing once, and a man paddled over and invited him to his place for soup. Leo said yes and the man drove him deep into the jungle, to his tree house, where a dozen or so Brazilian backpackers were staying—smoking, playing guitar, doing yoga, sleeping with one another.

“So I guess that vibe still exists,” Sasha says. “It’s just hidden.”

I message Leo about the jungle soup experience and where I might be able to find something similar. “Your best bet would be to go to the Arts Factory maybe?” he writes back. I search the Arts Factory in my maps app, and it directs me away from the main town through Byronic suburbia, where every second house is For Sale or Under Construction.

On the way I pass an esoteric bookshop. Inside, a pan-flute version of the Lord of the Rings soundtrack plays. A handful of customers are browsing the impressive crystal collection. There is an obelisk of black tourmaline on sale for several thousand dollars. I approach the counter where a small, neat man is sorting through a pile of books: The Body Keeps the Score, The Bone Broth Secret, and The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health.

“Do you happen to have a copy of Shantaram?” I ask. He nods solemnly. His hair, graying at the roots, is dyed henna red, parted down the middle, framing his weathered though well-manicured face. He leads me to a shelf filled with backpacker classics: On the Road (1957), Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974), Into the Wild (1996), 12 Rules for Life (2018).

“It seems we’ve sold out,” he says with an exaggerated frown. “But if you’re into that sort of thing may I suggest a personal favourite of mine, Wild, I think it’s called, by that woman who goes on a hike. What’s her name again?”

“Cheryl Strayed?” I offer.

“Yes, that’s her,” he says. “I did that same hike along the Pacific Trail last year. It took me five and a half months. I was so stagnant beforehand, after the Covid nightmare. Being back out on the trail was what I needed. It reminded me why I need to keep moving. Now if you’ll excuse me.”

He walks back to the counter to attend to a beautiful young woman wearing a red felt hat with a single cockatoo feather in it.

“How have you been?” he asks, holding out his hands.

“My body has been sick for maybe a month, but my spirit has been very strong,” she says. “How are you?”

“I’ve changed my diet recently,” he says. “Six to eight weeks ago I decided to basically cut out vegetables and now eat only meat.”

“And how are you feeling?”

“It’s too early to tell,” he says.

I buy a small amethyst crystal (reportedly good for gut health and endocrine function) and continue towards the Arts Factory. At the entrance I read a sign outlining the property’s recent history. In the first half of the twentieth century, it was a piggery. In the 1970s it became a commune. In the 1980s it was a live music venue. In the 1990s, it became a backpacker’s hostel—and there it has remained stuck in time.

Inside I see a white guy with dreadlocks lounging in a hammock, a young woman with flowing hair and a nose ring practicing circus tricks, and a man with a mohawk, matted beard, tribal tattoo, strumming a comically small acoustic guitar. I watch three couples planning their onward travel up the east coast. I can’t tell if they’re a group or if they’ve met here, but they seem to be coupled off in hierarchical order of hotness—hottest guy with hottest girl, and so on. It reminds me of the sexual anxiety of backpacking, the stifling heterosexuality of the whole experience, the aggressive machismo and Mother Nature-style femininity. It is, from this vantage, deeply unappealing. But on the other hand, the crowd at the Arts Factory is undoubtedly the most diverse I have encountered since arriving in Byron Bay. There are people from all around the world here, unlike in town, which is almost shockingly white. I guess that despite the back to nature posturing, the backpacker is ultimately a cosmopolitan. Their citizen of the world lifestyle demands open borders and a kind of charming commitment to rootlessness.

In the courtyard, sitting alone, I see a young guy reading on an iPad covered in stickers: a Charles Manson sticker, a Che Guevara sticker, a magic mushroom sticker. I ask him if I can sit down. His name is Theo, and he comes from a small town in the center of Germany. He is 19, skinny and bug-eyed, wearing a tattered pink T-shirt, gray sweatpants, black oversized skate shoes, and horn-rimmed glasses. In front of him is a weed grinder, rolling tobacco, and three roaches. I ask him if he is staying at the Arts Factory.

“No ways,” he says. “Too expensive. I just like to chill out here.”

He tells me he arrived in Sydney six weeks earlier, stayed there for a few nights and then caught the bus to Byron Bay. He paid $66 for one night’s accommodation in an all male six bed bunk at the Arts Factory and then the next day he bought a cheap tent and set up a camp on the densely forested fringe of a nearby swampland.

“It’s really beautiful,” he says. “There is a daybed and I put up a hammock and fireflies. Or what are they called in English, the small lights.”

“Fairy lights?”

“Oh yes, fairy lights. Do you want me to show you?”

We leave the hostel and walk down a road back in the direction of town.

“Is this your first trip?” I ask him.

“I have taken LSD around six times.”

“No, I mean as a backpacker,” I say.

“Yes, it is my first time outside of Europe. My parents wanted me to straight away go to the university and study to become a pharmacist. That was my plan. But then I read The Motorcycle Diaries and it changed my perspective on life. I wanted to be something different.”

He tells me that after reading Che’s memoir, he made plans to travel to South America, buy a motorcycle and ride it from north to south. But his parents wouldn’t give him any allowance if he did.

“They didn’t even want me to come to Australia,” he says. “My mum got scared after she read about the missing backpacker.”

Sasha had already told me about the missing backpacker, a 19-year-old Belgian guy named Theo Hayes, who disappeared one night in 2019 after being kicked out of a nightclub called Cheeky Monkeys. Many townspeople became kind of obsessed with Theo’s disappearance, Sasha said. Some thought that he slipped while trying to climb Cape Byron headland to get back into town and was then washed out to sea. And others believed that he encountered one of the shady characters who now dwell in the forests outside town.

“Strange, your name is also Theo,” I say to Theo.

“That’s what my mother says,” he says with his bug-eyed smile. “She’s very irrational.”

We walk up a clearing underneath power lines past a tent around which are strewn several empty beer cans.

“That belongs to another woman who is camping,” Theo says. “She’s maybe 50 or something. I think she is homeless.”

After a few hundred meters Theo says, “here we are.” We walk into the thick bushland where there is a tent covered in palm fronds, a hammock strung between two trees, and an old, soiled mattress, onto which Theo flings himself and starts to roll a joint.

“This is my own little paradise,” he says. “Try the hammock.”

I lay back in the hammock and Theo tells me about a novel he is working on. The premise is as follows. Humans have engineered trees to grow extremely large and they live in cities built in the trees in symbiosis with nature until the humans begin to exploit the trees, so the trees have no choice but to grow inwards and destroy themselves before the humans do.

“But there’s a twist,” Theo says with a dramatic pause. “You find out at the end that the whole story is told by an alien to his child to pass on a message that we shouldn’t destroy nature. It is like a metaphor for climate change.”

I wish Theo good luck with the novel and walk back into town. I order a kebab from a kebab shop that has been on this corner since I first visited as a 17-year old, where there used to be a line outside at lunchtime. Now there is a line at the Acai bowl place. But enough of that. Enough has already been said about how Byron Bay has changed. And to repeat it would be to fall into one of the most irritating backpacker tropes—lamenting paradise lost despite being part of its destruction. The backpacker has always chased a self-defeating ideal.

*

That evening I finally get around to watching Apple TV’s Shantaram. It is far worse than I ever imagined. Gregory David Roberts’ on-screen persona, “Linbaba,” played by Charlie Hunnam, is utterly lifeless—a kind of hollowed out Alpha on an unconvincing and superfluous hero’s journey to nowhere. He has this unplaceable accent—part Irish, part Australian, part Texan? A citizen of the world?

Much happens in this first episode. Linbaba escapes prison, arrives in Bombay, and meets his future love interest—the alluring Swiss businesswoman, Karla, in a swanky Bombay bar. After several enjoyable evenings together, Karla grows serious and asks Lin to help her rescue a friend from a high-end brothel, where the woman is being kept prisoner by one of the city’s most feared Madames.

“I... look, Karla, I’m sorry, but I can’t,” a pained Linbaba says.

“You could,” she retorts. She tells him that she can sense that he’s not just another tourist out to see the world, but that he is in Bombay for some other reason. Linbaba looks at the floor, suddenly exposed.

“Everyone here is running away from something,” Karla says.

“Yeah, I know,” Linbaba replies. “And I plan to keep right on going.”

“It doesn’t work,” Karla says. “Trust me. You can be free of anything but yourself.”

I close my laptop and wonder who in the world could make it through a show like this. Maybe Theo, I think, if there was adequate 5G in his stretch of the jungle.

A few weeks later, the show was canceled.