Reply Guy, Resurrected

Sally Olds attends Jordan Peterson's stadium show

The name on my e-ticket is not Sally Olds. After fruitless requests for a press pass, I paid my own way to Jordan Peterson’s lecture at Melbourne’s Rod Laver Arena in November last year, and—seeing as the event had nearly sold out—was allocated someone’s returned ticket. Tonight, I’m not Sally Olds. Tonight, I’m Garrett Megg.

The Batman Avenue Bridge, which spans the train tracks to the Arena, is a funnel of men. Here, if you want to indulge that sort of thing, you can find every AMAB archetype on God’s green earth. There are triangular torsos atop puny legs. There are strutting, bubble-butted men with Chad jawlines. There are long, otherworldly boys with deep gouges of pimples on their cheeks who bob among clouds of their own hair as they walk. There are friend groups of ruddy-cheeked, round-bellied dads in jorts and checkered shirts (Garrett’s friends, I imagine). No one pays any particular attention to me.

The section that leads from the bridge to the Arena is one of those sad afterthought areas that occur in most capital cities: large planes of concrete, a curvy mess of roads, and pointless, sculptural white monoliths. It looks like the outskirts of any airport in the world, as though some androcidal disaster has hit the city and Melbourne is evacuating a select portion of its male population. Outside the Arena in the line to get in, I start to sweat, wondering if the wrong name is a problem. But Garrett goes through without a hitch, buys a Smirnoff Ice, and shoulders his way into the stadium.

I am seated at the very back of the Arena next to a Sontag-style beauty, a Southsider in a brown suit whose husband hates Peterson but whose friends are into him. On my other side is a thirty-something man, white T-shirt, blonde hair. I chat to them both and discern that we are all here simply to “see what it’s all about.” Only the tickets were $220 for these terrible seats on a balmy Saturday night, so either we are all rich and idle or there’s something we’re not telling.

The truth is, though, I don’t really know why I’m here, except that I am operating on one of those hunches that makes me do things and then write about them. I have so far managed to largely avoid engaging with the whole Peterson phenomena, beyond reading his tweets and fielding the occasional Peterson stan in my undergrad classes. I probably know as much as the average Twitter user. First, there was his spectacular rise to fame: from crabby university teacher and clinical psych, who spoke out in vehement opposition to a Canadian bill protecting gender expression and identity, to foremost hater of “woke moralism” and the “radical left,” to bestselling author of 2018’s Jungian/manosphere self-help book de rigueur, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Next, the downward spiral: benzo addiction, total gut biome collapse, an induced coma in a Russian treatment facility, and, most recently, the end of his tenured Professorship.

Now, it seems, Peterson is enjoying what I imagine he sees as his Christlike resurrection. He has a new book out, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life (2021), and a global publicity tour in full swing. Last time he was in Melbourne, in 2019, he spoke to a crowd of 5,000 people. This time, he has filled out a venue with a capacity of 15,000. If I once nursed tender hope that Peterson would simply fade away, he feels finally unavoidable, and therefore worth paying attention to. Am I a casualty in Jordan Peterson’s war of attrition? No, I tell myself, I’m journalist-adjacent. I am here to investigate. I want to figure out the source of his strange and enduring appeal, not succumb to it. As the lights dim and a cheer goes up the lady in brown offers a provisional answer, whispering in a resolute tone, “I like him, I think he’s a good man.”

Jordan Peterson does not enter, not yet. First, the giant screens light up with an infomercial for an app that Jordan and his son Julian have just launched. The ad is a highly-produced short film that opens with Peterson claiming “writing is the deepest form of thought” but that few people really know how to do it. Enter “Essay,” a Grammarly-style, semi-automated tool for writing, editing, and restructuring essays. The camera tracks through libraries, Bushwick lofts, a pond where father and son are conversing. The film climaxes with Jordan’s voice booming over urgent orchestral music: “Essay means to attempt! To try!...Aim up, man, aim up, and put everything you have behind ya.”

As I am watching the ad, I am shocked by a) Jordan Peterson’s respect for essayists (yours truly…? Should I mail him People who Lunch….?) and b) how much he sounds like a liberal, small l, like one of his own sworn enemies—he could be a blue-haired Bookstagrammer espousing the power of words. I am also pleased to have witnessed the launch of a new Peterson, Julian, who has stayed out of the limelight until now. Jordan Peterson has always needed his family for credibility and content, and Julian’s sudden involvement seems like an expansionary tactic. So far we’ve had access to Tammy (Jordan’s wife, mother of his children), most famous for her miraculously-cured cancer, and Mikhaila (Tammy and Jordan’s firstborn), a spray-tanned wellness influencer who cured her father’s upset tummy with an all-meat diet. Julian enters the public sphere as a mousy, polite young man interested in coding and music: the soft-power wing of the Peterson-industrial-complex.

The lights dim again, but this time a woman strides out—and sure enough, it’s Tammy, here to introduce her hubby. The crowd claps, but it’s far less enthusiastic; we’re all getting impatient. In person, Tammy has a supremely erect carriage, a hooked witch’s nose, wears an asymmetrical sack dress, and speaks, shockingly, with the high, breathy voice of a little girl. These attributes combine to produce a frightening result—she appears both quirky and remorseless at the same time, an effect I’ve observed mostly in certain child care professionals and Yoginis (which Tammy is). I’m fixated on her baby voice and struggling to apprehend the meaning of what she’s saying, which is not purely my fault, as her remarks are circuitous and halting. She recounts, at length, an incident in which Jordan interrupted her while she was on an important Zoom call. He wanted to know where his socks were. She snapped at him, then deeply regretted her ungenerous behaviour. Her role tonight, I think, is a very Christian, wifely one: to provide a warm, motherly welcome before the entrance of the disciplinarian daddy.

The lights dim for a third time. A notice on the screen strictly prohibits recordings of any kind. I open my phone and press record. Spotlights rove around the stadium, displaying the makeshift rows covering what would normally be the tennis court. Jordan Peterson finally enters, and despite myself I’m grinning and clapping along with everyone else. The first thing I notice is that Peterson is taller than I expected. The second thing I notice is that he is wearing a strange and clownish suit. This is his custom-made Heaven and Hell suit, I find out later. One half of the blazer is blue and one side maroon; the blue is sheep’s wool, the maroon is goats’, and the lining of each corresponding side is printed with a blue sky and a red inferno. The crowd falls silent, expectant.

“Existence is predicated on deep suffering,” he announces.

Suffering is a perennial Jordan favourite. In 12 Rules, the word “suffering” appears 108 times; the phrase “life is suffering” appears five. In Beyond Order, “suffering” appears a mere if devilish 66 times, but gets a full-length treatment in the final chapter/rule: “Be grateful in spite of your suffering.” This rule forms the basis of his lecture tonight. He speaks without notes, with a preacher’s intonation. He talks about what amounts to a form of chaos magic: of acting as if you believe something until it becomes real. He tells the crowd to take a chance, to wager that life is worth living in spite of suffering, to practise gratitude, and through this practice, perhaps discover that you have made life worth living. He closes his eyes a lot while talking.

Despite this sound philosophy, the punters in Section 44, Row BB, myself included, are growing more aggrieved by the second. Immense chaos is unfolding around us in the form of the biggest seat mix-up of all time. People keep arriving and insisting that other people are in their seats. There is a furious whisper-argument raging. Families are divided; wives turn on husbands. I grow skeptical of what I’m hearing. If suffering is universal, why are Jordan’s solutions always about individual change? If he really cared, wouldn’t he want at least some collective action or policy overhauls? “Gratitude in the face of suffering has a martial attitude,” Peterson exclaims, as yet another seatless couple arrives on the scene.

Throughout the lecture, Peterson interweaves his maxims with stories drawn from the Bible and from classic (Western, white, male) literature. The “Essay” infomercial initially seemed like an opportunistic grab for the attention of his captive fans, but now I sense a deeper connection. Peterson, I think, is a mid Montaigne, writing in the Americanised tradition of the personal essay: associative, didactic, and indulgent. His books are roving patchworks of childhood anecdotes and quirky allusions that resolve into steely prescriptions. When he is throwing out ideas and stories, he is opening up possibilities that could go anywhere, and the shame is that they terminate in the most reductive versions of themselves. He loves narrative and draws on novels frequently (he especially loves the Russians), but only in order to convey the moral of the story. His posture of the whisky-swilling old-fashioned gent makes perfect sense. He wants so badly to be in a Victorian-era men’s club chewing over Darwin and Tolstoy and encountering women only when they come to serve him sides of roast beef.

Instead, Peterson cut his teeth on—and here, you will never guess what I’m about to say unless you know this already—the Q&A website Quora. You’ve heard about the Reddit to alt-right pipeline, the 8Chan to fascist pipeline, but at the end of the Quora pipeline is Dr Peterson. On Quora, users pose questions and problems, and other users answer them. On Quora, Peterson writes in his intro to 12 Rules, he became extremely upvoted for his answers to questions on the meaning of life and the pursuit of happiness. When a publisher got in touch off the back of his public profile in Canada, he sent her to Quora, and what resulted was the boomer equivalent of turning a Twitter thread into an essay collection. Once you know this, everything about Peterson becomes less fraught. He is not the devil incarnate. He is not a being of supreme wisdom. He is a Quora user who broke free.

It’s no surprise, then, that the best and most revealing part of the evening is the Q&A. Two armchairs are wheeled in, and Tammy comes back out to pose the audience-submitted questions.

“I like to hear all the murmuring,” she purrs. “Murmurmurmurmur. All the thoughts that he’s pulling up [pause] inside of you. So now we’re gonna do Q&A. I picked out some of the nasty questions you gave me. So now I’ll invite him back on stage—Dr Peterson!”

Jordan settles into a chair, and quips, “How you doin’.”

Pause. “Grateful to be here,” she says. Laughter from the crowd.

“That’s good, that’s courageous.” More laughter.

All of the questions are worded in a deferential tone. The juiciest one reads: “How has the normalisation of pornography and explicit sexual content affected today’s society?” Tammy’s voice dips a little as she reads it, imbuing the question with sorrow. A spontaneous cheer breaks out.

“Woo, let’s go there!” yells a heckler.

“Well, I’ll tell ya something that you might not know. This is quite interesting…” He goes on to describe his study of antisocial behaviours in criminals, and the “constellation” of behaviours associated with “psychopathy.” One of these behaviours is “short term mating strategies.” Essentially (and I’m not being hyperbolic here), he is claiming watching porn can make you a psychopath. Furthermore: “If you’re gonna go out there and establish a genuine relationship, how bloody desperate do you need to be? And the answer is, not zero desperate. Pornography enables zero desperation, and life is too hard for zero desperation to be the right amount of motivation.” With a chill, I remember what day it is: November 26th. No Nut November is drawing to a close. Peak desperation is nigh.

As soon as Jordan Peterson wraps up (“What are you doing here? The answer is something like, you’re trying to aim up…”) dozens of people in my section leap to their feet and start charging towards the exit. As punters stream past me in the entrance hall, I get a better sense of what kinds of people are here. A man of the cloth—white dog’s collar, robes—and his lanky male companion have a fey, faggy air as they walk and talk. There is a gaggle of stunning women in hijabs, trailing two mid-thirties ladies in Gorman-esque print dresses and Doc Martens. Most of the T-shirts are plain, but the best T-shirt I see has text on it saying “SOCIALIST DISTANCING (STAY AWAY FROM SOCIALISTS 100+KM).” No one, absolutely no one, is wearing a cloth mask, surgical mask, an N95, or a mask of any kind.

The toilets closest to my seats happen to be gender neutral, and men and women jostle amiably at the basins—a strong argument, surely, for the ungendered loo, despite what Jordan might say on the matter. As I let myself into an oddly clean cubicle and lower myself onto the sparkling porcelain, I’m feeling tentatively positive about what I’ve witnessed tonight. But then I open my phone and Jordan’s most recent tweet pops up. “I could really do without the land acknowledgement propaganda,” he has tweeted at Qantas, which plays an Acknowledgement of Country during their touch-down videos. The good feelings vanish. I am confronted, all over again, by the other Jordan. Because, as we all know by now, there are at least two Jordans: the curious, kindly, essayist and the reactionary, aggro, troll.

What do people see in such a man? And which Jordan do they see when they look at him? You often hear his fans talking about how they pick and choose the parts of JP that speak to them, and the implication is always that they get into the self-help stuff and ignore the deranged political commentary. It’s easy to forget that “picking and choosing” cuts both ways, and that there is a whole other subset of fans who ignore the self-help and follow him for his politics. In the case of Dr Peterson, it’s not so much about separating the essayist from the troll but about the slipperiness of him having it both ways—a slipperiness that, to my mind, undermines both versions of Jordan Peterson. For the man himself, though, it’s working nicely. In fact, it might just be the secret to his success. It means he can pull followers from all walks of life, and from all points on the political compass. As the culture populates with niche identities and identifications—evidenced in the splendid array of people promenading the halls of the Arena—the Peterson empire generates enough contradictions to house them all.

After the show, on the tram home, I read through Jordan’s old posts on Quora. To a suicidally depressed man, Peterson recommended three of his own lectures and a self-help app he had recently released. I read the famous post, the one where he lists forty-two rules for life, from which he selected the first set of twelve rules, and then the next twelve for the latest book. The third Jordan, the most important Jordan of all, is the Quora reply guy, the man who has built a career selling banal, actionable, and marketable answers to life’s most difficult questions. I know, of course, that I paid Jordan Peterson $220 to arrive at this conclusion. Garrett Megg was a savvier man than me. He stayed home while I, like so many before me, sought answers from a consummate salesman.

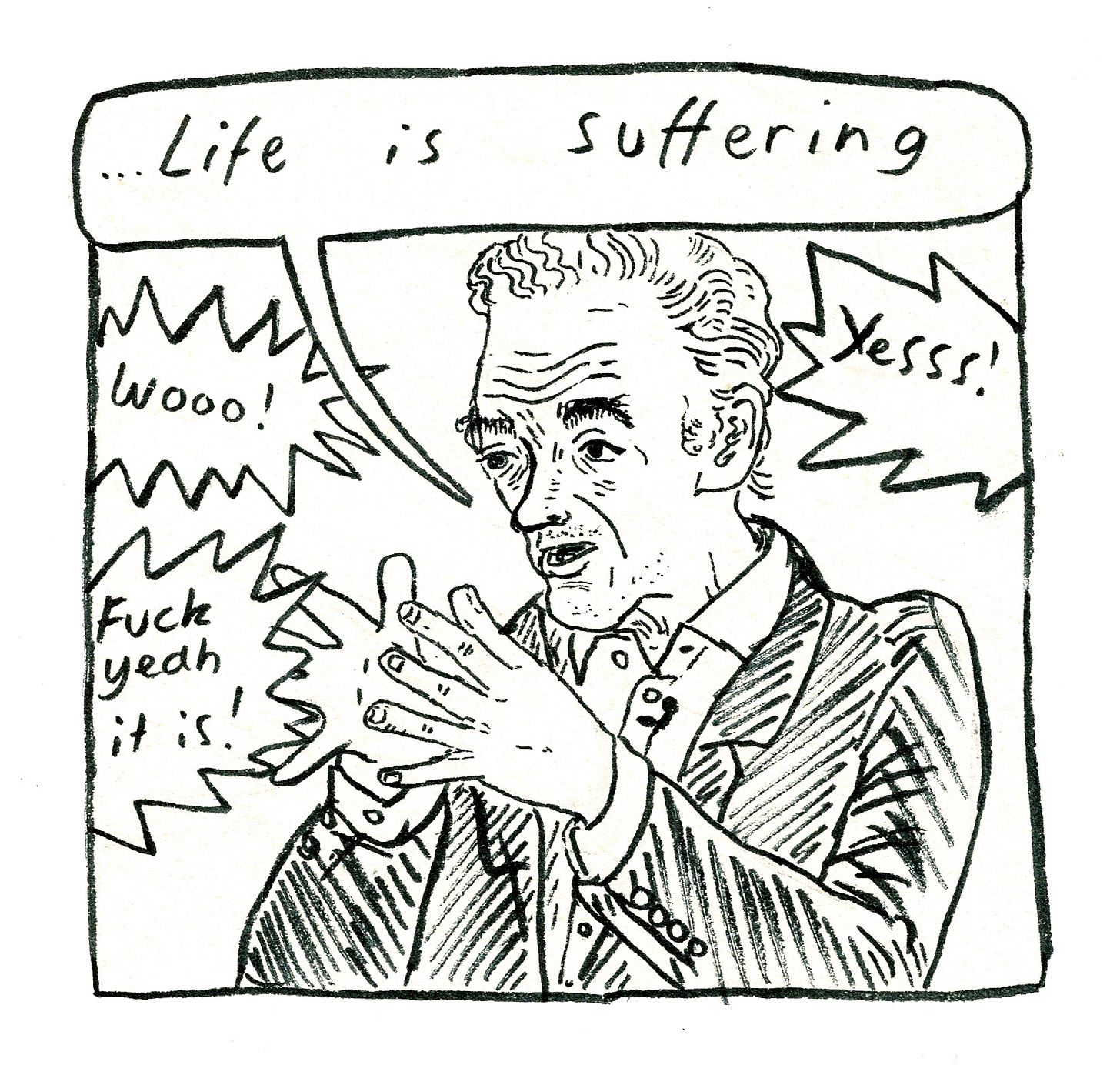

Comic by Aaron Billings