Who’s Afraid of the Green-Haired Girls?

There is gender trouble on the University of Melbourne campus. Cameron Hurst investigates.

It’s a blue-sky winter Tuesday at the University of Melbourne. The freshly mowed South Lawn grass looks obscenely green in the late afternoon sun. One of the six Wurundjeri seasons, Guling (orchid season), has begun, and a Muyan, or Silver Wattle, sports a Hi-Vis explosion of yellow blossoms. A couple of Arts enbies repping skirts-over-jeans sit cross-legged, discussing comedowns and due dates. Some Science nerds kick a soccer ball. A glamorous young woman in stilettos and an academic gown—I’d bet Business school—poses for a personal camera crew. The neo-Gothic clock tower watches over the seemingly carefree students. Like many of the university’s historic buildings, the tower is sandstone, but one could squint and almost imagine it as…ivory. Everything looks perfect. It’s not.

In late June, two people smashed and graffitied the windows of the uni’s Sidney Myer Asia Centre building on Swanston St. The graffiti was reported to be along the lines of “Trans—we are not safe,” and was implicitly directed at Holly Lawford-Smith, a controversial Associate Professor in Political Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts. Vice-Chancellor Duncan Maskell sent an email to the entire university condemning the street artists, writing:

Let me be unequivocally clear—such intentional acts of damage, violence, or vilification against others will not be tolerated. Resorting to violence and causing damage to our campuses is disgraceful.

This kind of violent behaviour is never the right answer, especially in the context of an inclusive university environment where freedom to express ideas and speech must be fostered and not shut down, and where differences must be worked through together through respectful, reasoned discourse.

Facts. Logic. Smackdown. But was property damage really the biggest issue here? President of the University’s National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) Branch, David Gonzalez, didn’t think so. He penned a public response to the VC’s email:

Professor Maskell was uncharacteristically scathing in his attack on activists fighting for the equality of Trans people.

If Professor Maskell had taken action to protest the rights of Trans people and stop the drumbeat of vilification under the guise of “academic freedom,” things may not have escalated to this point.

We would not have the rights we have today without people who were willing to stand up and act.

Life went on. Semester two began. A new Malaysian lunch spot opened in the student precinct. Many people on campus remained oblivious to any conflict. But in some corners of the university, anxieties and animosities lingered. Depending on who you ask, the University of Melbourne may currently be: a haven for Nazi-adjacent trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) who are cynically weaponising the concept of free speech as a way to whisper literal violence into the ears of impressionable young people; or a censorious playground for raving mad trans youths and green-haired elites who want to stomp on free speech with their chunky vegan leather boots. Reality is, obviously, far more complex.

The fractious conflicts about trans rights on campus have been most evident around the activities of and responses to Lawford-Smith. Lawford-Smith is a New Zealander in her early 40s who joined the university in 2017. Previously, she’d worked on philosophising the politics of climate change and citizens’ culpability for their state’s actions—thorny, important, snore-producing issues. But as her career progressed, she shifted to writing about feminism, sex, and gender, positioning herself as a part of the growing “gender critical” movement.

Some see gender critical figures as inheritors of a legacy of a particular kind of 1970s radical, often lesbian separatist, feminism, hence the popular moniker “TERF.” (One trenchant critic, Andrea Long Chu, has argued this acronym suffers from a “historiographic sleight of hand”; it implies that “all TERFs are holdouts who missed the third wave, old-school radical feminists who never learned any better.”) Others see the loose coalition as part of a reactionary backlash to advancements in queer and trans rights. Others still reckon they’re nutcases hiding bigotry behind a polite name.

Lawford-Smith has made choices that many in the academic community view as strange and ill-advised at best, and downright ethically unacceptable at worst. In 2021, she launched a public website for people to submit anonymous stories about gender self-identification laws. In practice, the result was a bunch of sad, random, and paranoid anecdotes—basically, a transphobic Reddit forum with sombre website design and grave political messaging. It was hardly peer-reviewable. Thousands of academics and students signed an open letter criticising the site. Undaunted, Lawford-Smith continued teaching a class titled “Feminism,” which, according to the subject guide, turns to second wave feminist arguments to interpret a range of present-day issues. Students argued that the subject included materials framed and taught in a way that vilified trans people, and tried to have it shut down; “Feminism” was reviewed but ultimately allowed to continue.

Beyond the classroom, Lawford-Smith’s social media activities show a strong personal commitment to gender critical politics, alongside a propensity for trolling (one screenshot shared by an activist group, for example, seems to show the philosopher posting vomit-face emojis next to an image of a trans flag being pasted up at the university). In March this year, she spoke at the “Let Women Speak” anti-trans rights rally headlined by Posie Parker. Parker is a Brit who has made a career out of arguing that trans people do not exist (that’s her least offensive talking point). Sieg-heiling neo-Nazis appeared in support of the speakers. Organisers later said that the fascists were just opportunistic gatecrashers, there to punch on with the anti-fascists. Yet some critics wondered why the attendees hadn’t actively opposed the menacing white supremacists at the time, nor, in the aftermath, done some self-searching about why the public display of allegiance had transpired.

In any case, it was a PR disaster. Students ramped up protest actions at the university in the aftermath, insisting that Lawford-Smith had gone beyond the bounds of acceptable behaviour. Campaigns by an anonymous group called “Fight Transphobia UniMelb” attempted to discourage students from taking Lawford-Smith’s subject (see: the “Only a fascist takes Feminism” sticker). After this tactic was criticised by the Dean of Arts, the sticker-makers quietly acknowledged the admonishment but reiterated the legitimacy of their campaign. Then came the window smashing. Lawford-Smith is currently embroiled in a legal battle with the university, arguing that she has been subject to an unsafe workplace. These events have received widespread media coverage in The Age, The Australian, and Sky News, among others.

Why do I care? Firstly, I’m an ally, duh. I disagree with Lawford-Smith on basically everything she says about trans rights (and sex worker rights, but that’s another story). But over the past few years, I’ve observed that the strategies deployed to oppose her have been ineffective. More than that—I have at times worried they may be self-defeating. Her ideas haven’t disappeared from popular discourse, but have arguably been amplified by publicity. Media coverage of her scuffles with the university bureaucracy and student activists has become increasingly frequent and complimentary. Now, if she gets fired, she’ll be a free speech martyr. Yet throughout all this, gender studies, the discipline seemingly best-placed to offer alternatives to gender critical talking points, has struggled to articulate compelling public responses. I speak from inside the house; I’ve both studied and taught gender studies subjects at the university. I’m also a massive feminist loser—the kind of person who took Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex on family camping trips as a teenager.

I care about the uni’s capacity to function as a forum to discuss complex ideas about gender. I still believe that a university should be an arena where research developed through rigorous exchanges with others can, like, contribute to a better society! There’s more at stake here than a series of tiffs between one professor, a bunch of freaked out students, and a risk-averse corporate institution. Reading the news, it can sometimes seem like there is a conspiracy to eliminate conversations about complex gender issues. Is this actually true? Over the past few weeks, I’ve talked to a lot of people connected to this situation—including Lawford-Smith. And to speak in the parlance of a news.com article, what I found shocked me.

*

None of the gender studies academics in full-time roles at the university spoke to me on the record. I spoke to some off the record and can report that people are doing stuff behind the scenes. They’re tired, overworked, worried about being implicated in litigation, scared of losing their jobs, fretting that giving oxygen to bigoted ideas will just make queer people more vulnerable. Speaking about gender in prominent public contexts can provoke vicious trolling. I get why people don’t want to do it. But since I’ve never yet been weighed down by a full-time contract, I have had ample time to think about the lack of meaningful public discussion about gender, feminism, and trans rights in Australia. A lot of discourses on gender are imported from the US and the UK—two contexts where debates about trans rights are playing out very publicly and very differently. In Australia, some right-wing politicians look to Trumpist politics for tactics; some queer kids approach American YouTube videos like they’re a bottle of amyl at Sircuit (sniff deeply; feel the rush). But Naarm is not mumsnet or Florida. I enjoy ContraPoints’ weary drawl just as much as the next person, but not everything she says can be applied wholesale to our little settler-colonial outpost.

Now, in the university’s backyard, there is a toxic void of non-conversation around Lawford-Smith, especially from the Chancellery. Everything has ended up framed around academic freedom and censorship, the good people and bad people—not the ideas. (I know the ideas are dubious. I’m getting there.) An illusion has developed, or been propagated deliberately: people fighting for trans rights are shutting down discussion. They’re unable to articulate positive positions, only offer negative critique and outrage. Ergo, maybe there’s some truth to what the persecuted free speech advocates are saying. Maybe gender radicals really are ruining our universities! A niggling paranoia had begun to develop in my head: what if some of what Lawford-Smith says is actually reasonable? What if an opportunity for constructive feminist dialogue is being lost? There’s nothing like someone dramatically proclaiming that they’re being censored to make you wonder about what they’re actually trying to say.

First, I wanted to hear from some gender studies-affiliated youths. These were the supposed serial cancellers—the tweaked-out snowflake SJWs. Would they talk? Yes, though most preferred pseudonyms. Using your real name to shitpost on the internet and pretend it’s politics is so painfully millennial.

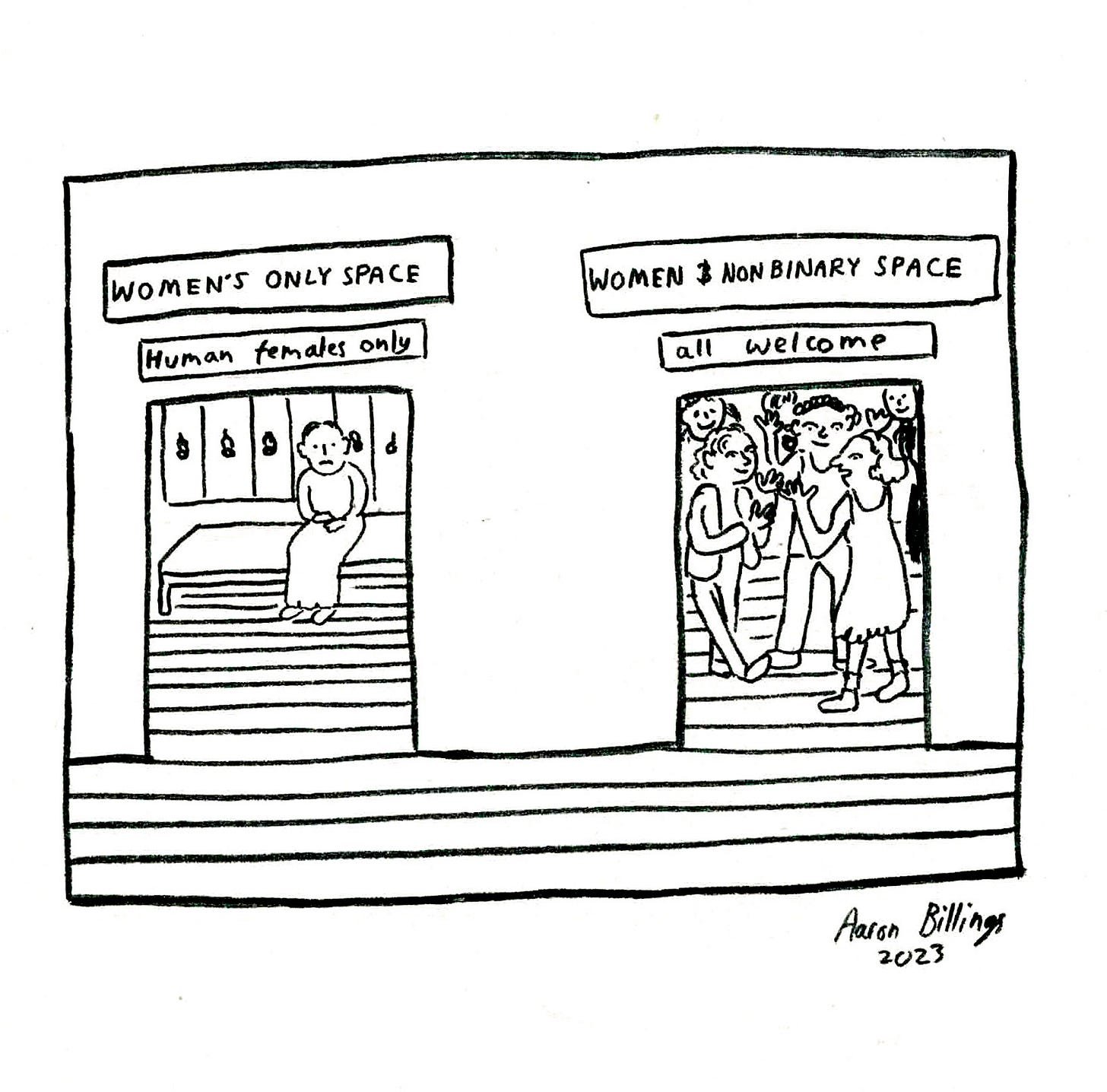

Sheila Jeffreys-Star and I meet at a bar in Thornbury. She’s a slender girl with bangs and a penchant for decisive strokes of black eyeliner. We first met in a bathroom at Miscellania. She’s a former gender studies student and current tutor, so we have a lot to talk about. In fact, one could say we’re a couple of girls with very similar “lived experiences,” except one of us is cis and the other is trans. We cover positionality and tute trauma-dumping: how experience does shape knowledge, but academic discussions tend to go better when people actually read and engage with assigned texts. We discuss how third wave feminism and queer theory have been great at coming up with intellectually engaging abstractions, but it’s a struggle to apply these to real world contexts. For example, in the controversies around “women’s spaces,” Judith Butler’s concept of performativity hasn’t done much to convince gender critical figures that bathroom access should not be divided by binary sex. Sheila has her own criticisms.

“The gotcha I have for that conversation is to ask: what, you want a hairy trans guy to go into the women's bathroom?” She laughs, then speaks more seriously. “They are implicitly asking for the state—for the Daddy-State—to regulate these spaces to like, ‘protect women.’” She thinks this strategy is unrealistic in this specific instance, and not always a desirable position for activism in general. Instead, she errs towards fighting for social and cultural change without calling in the firm, masculine hand of external authority. “When I think about the ‘70s, there’s this idea that ‘women are doing things for themselves.’ Not to be overly romantic about that era, but…I do respect that approach to organising.”

I ask her what she thinks about trans healthcare discourse, something that the media often claims “no-one is talking about”—especially when it relates to minors. She thinks this sensitive topic is being discussed in gender studies classrooms, in the literature, and among peers. “When the children get involved is often when a discussion becomes a moral panic,” she says. “The argument that there is significant social pressure to change your gender is pretty fake. That’s such a miniscule pressure against the whole rest of the system. Nobody wants you to change your gender, really.” She does have criticisms of the inherently normalising framework of medicine—the investments healthcare professionals have in simplifying, curing, and fixing “problems.” This doesn’t necessarily allow for ambiguity or encourage exploration. When she thinks about sex and gender, Sheila is also sceptical of any frameworks that are ahistorical and foreground individual choice: “Our experiences are so regulated by society. We cannot make free decisions.”

Victoria is originally from Beijing, but is now an Australian citizen studying sociology in Japan. We took a class together in undergrad and since then have followed each other on Instagram, where I love to see her glittering posts showing her fine dining at exclusive Chanel couture events. Apparently the last one she went to in Paris was a bit disappointing (poor organisation and an overstacked schedule). The one in Tokyo, when Jennie from Blackpink performed, was way better. She’s back in Melbourne to visit her parents, so we catch up. I ask her how she ended up in gender studies. She loved writing about the social expectations placed on women and girls, especially in Chinese families, but says the main thing she took away from the discipline was critical thinking. “When I chat with my friends and family who are still in China, I feel like our kind of way and their kind of way of thinking is very different,” she says. “China has very strict censorship of publications, movies, books, and also posts online. A lot of things are banned. I learned a lot about freedom of speech and freedom of thinking here in Australia. Now, I feel like censorship is something that shouldn't happen.” She wasn’t following the controversies around Lawford-Smith, but had seen Emma Watson’s criticisms of J. K. Rowling. I asked what she thought about the discourse. It seemed like a low priority: for Victoria, “the core of this LGBT issue is that you can be whatever you want—nothing is rejected, but nothing is encouraged.” This probably wasn’t going to make it onto a Pride parade slogan, but it wasn’t the worst thing I’d heard that week.

Justine and I check out a UniMelb Socialist Alternative meeting about “Misogyny and Transphobia: the Social Construction of Gender.” Justine is a working class former jazz singer and a proper intellectual who is writing a thesis about the French psychoanalytic feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray. She’s another tutor committed to the discipline of gender studies, but worries that we’ve ended up in a “ridiculous dilemma where politics is about saying the right thing and political action is about stopping people from saying the wrong thing.” In her view, “TERF positions show inconsistencies within the epistemological framework of gender studies. The wrong move is to double down and become dogmatic, when we could just have better ideas.” She believes historical materialism and analysis of social reproduction are sorely missing from the equation. Another controversial opinion: Justine reckons that the most lively academic activity might be going on in para-institutional spaces like the Melbourne School of Continental Philosophy and the Clyde Hotel—places that are a “little less overdetermined by the restrictive weirdness of the corporate university.” That’s why she’s always at the pub (although apparently it’s recently been overrun by poets).

At the socialist meeting, I wonder if discussion will be all about Lawford-Smith. It isn’t. A fresh-faced young woman gives an earnest speech about how it is imperative to understand women’s oppression today as the product of a capitalist society. She presents a leftist critique of the popular concept of intersectionality, and attendees contribute to a vigorous debate on the topic. One even yanks a lanyard off while speaking because they’re so moved by thoughts of Marx. It’s a scene of idyllic student political engagement; I almost forget the Socialist Alternative’s unfortunate reputation as opportunistic door-to-door social justice salesmen. A week or so later, I see some students scurrying away from flyer-mongers hawking a Lenin and Stalin forum. “Be careful, folks!” one jokes to his friends. “They will harass you.”

Judy Sherman has nearly finished her social work degree and always looks glamorous, whether she’s in op-shop trackies or a black party dress. She is one of those people who seems intimidatingly cool and hot from afar, but is actually a chiller once you get to know her. Her main criticisms of gender studies were that we didn’t spend enough time discussing issues facing Indigenous women and women of colour (she’s Indigenous), some people in tutes were punishing (especially in righteous second year), and there was an insidious dismissal of the pleasures of femininity. “There was so much internalised misogyny,” she reflects. “I was like, ‘What's the point of this if we're just hating on women’s choices?’” When we speak about recent events, she emphasises the need to listen to the voices of trans people. “I think that the person whose identity is under attack—what they think is the most valid.”

Eva Rees is a literature student and theatre kid with a shock of bleached hair and an erudite, deliberative manner. She played the main role in the Harry Potter and the Cursed Child stage production, transitioning during the show’s run—a story that could seem like a satire of our times, except that it’s true. (She has complex feelings about J. K. Rowling.) She’s been involved in some protest actions on campus and says she has been responding to “a fundamental disagreement as to what rights are inalienable.” Intellectually, she understands the critical importance of academic freedom, but feels hurt, angry, and fatigued by what she sees as scapegoating of trans people, especially trans women. But, in spite of all the bad news, she is cautiously optimistic: “Do I have faith in people? Unfortunately, I do. I think that transphobia is an inherently illogical position and if one were to contemplate it in a way that is in good faith, one would come to that conclusion. Also, I'm not in the cult of rationality—I think there's a really important place for emotion in these debates.” Statistics suggest that real instances of violent or harmful scenarios feared by gender critical figures (for example, attacks in public bathrooms) are very low; Eva theorises that there are more emotive, affective undercurrents driving the tensions in public conversations.

“More than anything, this is all just fucking sad,” she says. “I don't want my identity to be the battleground upon which the culture war takes place.” While trans masc and non-binary people are in the sights of the gender critical movement too, trans women tend to attract the most ire in vicious public debates. Eva continues. “Most of my opinions and standpoints come from that place. And I mean this as a sign of respect—I think [Lawford-Smith’s ideas] probably do too. I'm not trying to denigrate her in any way. I think she's probably as emotional as I am.”

Everyone I spoke with had different preoccupations and ideas about gender in the university; none were dogmatic. There certainly isn’t a hegemonic bloc of Zoomer anti-free speech advocates blinded by rainbow ideology, or whatever The Australian columnists seem to think. People felt uneasy with the consequences that censoring Lawford-Smith might have for teaching controversial subjects more aligned with their own politics down the line. On the other hand, they were deeply suspicious of bad faith bigotry disguised as academic freedom. And these are the people at the coalface of the university—they’re participating in and facilitating classes, working through difficult ideas in their writing, contributing to para-institutional spaces. Nuanced conversations are happening. So why don’t they make it to the mainstream? Could it be that there are reasons outside of a supposed Marxist-feminist cancel culture war that stop people from talking about gender in public contexts?

*

I call Raewyn Connell for more insight. I’m sitting on the university lawn and my bum is growing increasingly damp, but I am focussing hard on our conversation—Connell is a legend. She is Professor Emerita at the University of Sydney and one of Australia’s most influential sociologists. In the 1980s, she coined the term “hegemonic masculinity,” which, if you’re in the world of gender scholarship, is like coining “cottagecore” or “YOLO.” She made it to the big league. She is also a trans woman who was born in 1944, so she’s seen a fair few shifts in gender norms in her time. Before we chat, Connell requests that I send through a list of questions. I comply at length; I’m desperate to impress her with my analysis of our current situation, which reaches back to women’s liberation and the New Left then shifts to a 30 year interpretation of the neoliberal managerial mindset underpinning our struggling tertiary education system. She quickly cuts me down to size.

“I've got your email. A large agenda that you've outlined, but I'm happy to work from that,” she says dryly. Connell’s writing is often acerbically chatty, with moments of moving sincerity amongst the macro leftist structural analysis. On the phone, she’s more serious than I anticipated, speaking slowly, softly, and thoughtfully. I ask how she ended up in sociology. She started studying history and psychology in the early 1960s, when universities were still conservative, extraordinarily elitist places run by “God-professors.” By the end of the decade, the world was changing.

“Bloody Menzies had sent troops to Vietnam to support the Americans. I was in the Labor Party, which had come out against the war,” she said. The women’s liberation movement was growing, as was the Aboriginal rights movement. “There seemed to be this enormous need for relevant knowledge. And what I was taught in my undergraduate degree was intellectually admirable, but, you know, it had nothing to say about the state of the world. I thought: what's the knowledge that really matters? Class, social movements, struggle, exploitation, violence, and so on. Where did you find that? Well, it seemed to be sociology.”

By the 1970s, she was working as a young academic, helping set up sociology programs and conducting new research. She published consistently and with increasing influence, especially in the burgeoning field of “gender studies,” which emerged from women’s studies—the academic arm of second wave feminism and the women’s liberation movement—then morphed to allow for analysis of masculinity and queer theory.

Throughout this time, Connell was a rank-and-file member of the Labor party. She met her wife, Pam, at a local branch event. But as the party changed direction in the 1980s, Connell grew increasingly alienated. “I left the Labor Party when Keating became leader,” she says. “That was the last straw for me.” Hawke and Keating’s market-driven agenda resulted in the privatisation of public assets “on an industrial scale.” Consequently, public life changed. “People were basically invited to think of their relationships with public sector institutions, whether that be public transport, public higher education, or schools, as a market—a buyer-seller relationship,” Connell says.

This neoliberal turn manifested in Labor minister John Dawkins’ radical reform of higher education policy. His well-intentioned aim was to broaden access—to allow more domestic students, especially from diverse backgrounds, to go to uni if they wanted to. Due to a larger economic downturn, politics demanded this happen without increasing public funding. Dawkins’ reforms introduced domestic fees and loosened regulations so that universities could teach more (higher fee-paying) international students. “We've been seeing the consequences of that ever since,” Connell tells me. In subsequent decades, student numbers massively increased; more and more international students came to learn in Australia. (Michael Wesley’s recent book on the sector, Mind of a Nation, notes that “in 2001 there were 842,183 students in Australia’s higher education sector; by 2020 that number had risen to 1,622,867, an increase of 92%.”) Tertiary education became a major Australian export. None of these developments are intrinsically bad. But to cope with the growth, universities started taking cues from the private sector—more managers, more KPIs, more ruthless budgeting and restructuring.

What was happening to the academic ants on the ground during all this? Connell remembers that her university axed the in-house travel agent, which made it harder for her to make arrangements to attend international conferences. More relatably, the working conditions of her younger colleagues became increasingly fraught; full-time workloads blew out, and a precarious workforce of casuals ballooned in response to the demands of the ever-expanding, entrepreneurial university. Now, Connell says, “we've got massive courses and classes which are radically understaffed, taught by teaching staff who are insecure, anxious, unprepared, and overworked. That’s before we even begin on corruption and wage theft.”

In February 2023, the Australian Financial Review reported that the University of Melbourne had repaid staff a total of $45 million. This followed searing scrutiny of widespread underpayment and mass casualisation in the sector. Distrust between university staff and management is widespread. Meanwhile, some see the current fee model contributing to a buyer-seller relationship dynamic between the student and the institution.

All this is to say: the reality of today’s university is very different to what we imagine the shining ideal to be—mahogany-panelled halls illuminated by the bright light of academic freedom, a place where robust debates are underpinned by a strong foundation of mutual respect and shared liberal democratic values. This is simply not the truth for many people. Is it fair to expect academics and students to be able to hold “respectful, reasoned discourse,” in VC Maskell’s words, when the conditions that make this possible have been so impoverished? The lights are on in all the shiny new buildings on campus, but is anybody home?

I wanted to hear the union’s perspective, so I check in with NTEU Branch President David Gonzalez. Gonzalez is a vivacious statement-glasses wearer from a family of education unionists. “People need to feel secure in their work to be able to speak up,” he tells me. “When the only model to get a permanent job is to suffer through as many contracts as you can—to be the last person standing—that’s basically impossible.” The union is currently gearing up to support branch members as they go on strike next week—the Arts Faculty, where gender studies is housed, is striking for the entire week. This escalation is driven by the branch’s sense that the university is not responding meaningfully to their bargaining priorities. I ask how the organising has been going. I’m particularly interested in hearing how Gonzalez sees the role of social media in the campaign; I’ve become increasingly sceptical of the widely-held 2010s notion that churning out content for Silicon Valley overlords results in substantial IRL change.

“Power comes through one-on-one conversations,” Gonzalez says. “Power comes with knowing what you can do to change the minds of the people you're organising against. Social media can help with resources and messaging, but does it actually build power? I don't think so. That's why I don't engage with it anymore. I feel like I'm seeing the fruits of what actual power is looking like, and it's not on a Twitter feed.”

Gonzalez is a member of the queer community and considers fighting for trans rights a personal issue. In his view, ideals of academic freedom cannot supersede workers’ rights to feel welcome on campus. And what’s more, academic freedom fundamentally depends on workers’ rights to feel welcome on campus. This feeds into the NTEU’s activities; the union is focussed on enacting social justice commitments through practical, not just symbolic, demands. They just won 30 days of paid gender affirmation leave for University of Melbourne staff, including for casuals. This is a big step in the right direction, Gonzalez says. But it didn’t come easily.

“The university protects freedom of speech for people who are vilifying other people, but has not given the same sort of support to the people who are affirming [other people]. This is where the multibillion dollar business model comes in, right? The university is corporatized in such a way that…not to use neoliberal, which I kind of hate because I just feel like it's inaccessible. I'm not an academic.” Gonzalez pauses briefly. He re-focuses. “It creates a situation where these issues are put into a risk management register. Like, ‘Oh, we're gonna piss off this group of people. We might scare away new students, so we'll plaster the campus with Pride flags and trans flags, but only until July.’” But for months, Gonzalez says, the university had said no to the union’s gender affirmation claim. “You're saying this one thing, but then you're not actually doing anything about making the material lives of these people better. Do you actually care or do you only care about your reputation?”

What do the Vice-Chancellor and the Dean of Arts have to say about this? Neither were available for interviews with The Paris End. But—to my surprise—Holly Lawford-Smith was.

*

I meet her at Dr Dax on Royal Parade. I’d suggested the Clyde as an option, imagining a kind of symbolic, lager-scented olive branch (the pub as a para-institutional neutral ground) but she wasn’t keen. Fair enough. I arrive at the cafe first, order a latte, and sit at a table by the window. I’m nervous; this is the Final Boss stage of my quest. A minute or so later, I see her walk in. She looks just like her photos: long, grey hair, tanned skin, green eyes, no makeup, Uniqlo-esque clothes.

“Holly!” I call out. “Hi. I’m Cameron.”

We shake hands. She laughs, looking a little surprised, then tells me she was expecting a man, and actually specifically a man with curly hair named Nick.

“Er, no,” I say. “Maybe you were thinking of Oscar?” (Nick aside, this gender misrecognition has happened to me for as long as I can remember; I cried after being put on the boy’s class attendance list in Year Two, and sometimes readers of my piercing feminist art criticism think I’m a way-out-of-line man…it’s not incidental that I have a deeply-felt sense of the arbitrariness of gender signs.)

Our conversation is far-reaching, and for the first hour or so, ping-pongs from friendly to tense and back again. She speaks with a Kiwi accent and an analytic philosopher’s rhetorical style, using terms like “moral agent” and structuring her arguments with logical propositions: if a) follows b), then c). For the most part, our conversation is combative in a weirdly enjoyable way. When I criticise her ideas, she fights back. It’s a far cry from the gentle, self-effacing mores of my feminist reading groups.

I ask her why she’s so drawn to the second wave and ‘80s radical feminism, noting that it’s a tendency I see more broadly in current feminist discourse. Natalie Wynn and Lauren Oyler are reading Andrea Dworkin; Andrea Long Chu has written at length about Ti-Grace Atkinson, Robin Morgan, and Valerie Solanas; Amia Srinavasan and Helen Hester share a fondness for Shulamith Firestone—so do this newsletter’s co-editors (Oscar even named his baby after her). Post-structuralists are out! Problematic girls are in!

“Mainstream feminism now doesn't seem to offer young women much by way of tools for diagnosing the situation they're in. And I think that's sad,” she says. For her, the 1970s and ‘80s was “when it was highly progressive to detach from the male-dominated left and insist on talking about women. That's the time where I think there’s the most exciting, radical, and interesting stuff. Before feminism got hyper-inclusive and became a doormat.” (Many would argue this shift aimed to address the feminist movement’s disproportionate focus on the rights of white, middle-class, heterosexual women in the West, to the exclusion of others. I don’t bring this up in the moment. I leave it aside and listen as she continues.)

Her ideal classroom is one where students “form deep intellectual relationships across moral and political lines.” One of her concerns is that the “left-dominated” university undermines this possibility; the institution will hand out rainbow lanyards and espouse support for Black Lives Matter, but doesn’t want to engage with the complexities of real cultural, political, and religious diversity. Here, one can’t help but think of many left-wing critics who have arrived at similar conclusions via entirely different pathways, though they would not agree that the university is materially left-dominated. (Horseshoe moment?) Lawford-Smith worries that the progressive hegemony is so intensely symbolic that students are more concerned about signalling their ideology via personal style choices than having substantive conversations.

“If everyone turns up in a grey sweatshirt and just sits together, that's very different than if some show up with green hair. Then you already know what their views on abortion probably are.”

“Do you?” I ask.

“You can assume you do. You’d probably get a reliable correlation,” Lawford-Smith says.

She’s not wrong, per se. You probably can guess that anyone with a rainbow mullet is pro-choice, but shouldn’t we at least try to leave our assumptions on the Swanston St tram stop and out of the classroom? Would university-mandated grey tracksuits really smooth over the tensions caused by everyday differences in belief?

She bristles when discussing the discourse about the neo-Nazis at the “Let Women Speak” rally. In her view, counter-protester posters displaying Posie Parker’s face with anti-fascist messaging are what drew the fascists to the event.

“They were nowhere near us!” she says. “We didn't know where they were. Even if we had, I think it's quite preposterous to think that we should have run fleeing from the venue as though there was a mouse.”

She ended up beefing with people pressuring her to publicly apologise on Twitter: “I felt like these were leftist men trying to control me or exercise power over me. They just showed up right in my Twitter feed and were like: ‘denounce Nazis or you love Nazis.’ I'm not doing that because a) I think it's stupid and b) I’m definitely not going to start grovelling on your terms because you’re requiring me to do that to pass some purity test.”

Ugh, Twitter.

I try out a thought experiment and imagine that the gender critical feminists and the pro trans rights feminists really want to sit down and have a dialogue grounded in mutual respect. Can Lawford-Smith see how the working conditions of the neoliberal university may have undermined this possibility?

She starts talking about her own disciplinary and legal battles with university management.

But what about other academics? “A lot of people might think ‘why would I wade into a contentious public conversation when I don’t trust the university to support me and I don’t know if I'm going to be able to pay my rent in three months time?’” I say, imagining she might have empathy for precarious tutors given her own mistrust of the uni. “What do you think about that?”

“Interesting. I certainly think that's a good reason not to speak up. And so to the extent that casualisation explains why more people who could be making useful contributions don't feel like they're able to, then I think that's bad. But I think I have, again, heretical views on the decasualisation movement.” I’m starting to wonder if “person with heretical views” is the identity Lawford-Smith most strongly connects with. She continues: “I think one consequence of the way the union is handling this is that they seem to just be pushing to make whoever happens to currently be casual, permanent. And that's really unmeritocratic. The people who end up hanging around for years and years doing just tutoring, they're by far not the most qualified and able people.”

I can almost hear the howls of rage from the branch office. Still: Lawford-Smith and I can agree that, in general, the university business model as it stands could probably be improved to create better learning conditions and a richer intellectual environment. In light of this, I ask if she’ll be supporting the NTEU’s upcoming strike action.

“I don’t know about that. I’m not in the union,” she says. “I feel very alienated from them because of their position on gender critical stuff, so I don’t really have a view.”

Some of her other positions are similarly vexing. Before our meeting, I read her recent book titled Gender Critical Feminism. It has a typically daggy academic cover: a yellow Converse sneaker next to a yellow stiletto (wow…which is the man’s shoe, and which is the woman’s?!). The copy from the University of Melbourne library looks like it has never been read.

In the introduction, Lawford-Smith draws a parallel between the present and an infamous rift in anglophone feminist history: the so-called “Sex Wars” of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Basically, conservative lesbian separatists and anti-porn campaigners teamed up with the Christian right to oppose what they saw as a coalition of degenerate queers, the BDSM community, and heterosexual oppressors at large. The split was extremely divisive, at times leading to physical confrontations and high profile legal disputes. “A similar opposition has emerged within the sex/gender heterodoxy today,” Lawford-Smith writes. But today’s conflicts are, to me anyway, not meaningfully similar at all.

Now, feminists mostly agree that the rebel dykes and their allies won the Sex Wars. This victory came about because they didn’t try to suppress complex expressions of gender and sexuality by leveraging the state and an alliance of religious conservatives. The instructional lesson seems to be that repression doesn’t work: those being censored today will ultimately be vindicated as being on the right side of history. Yet elsewhere, Lawford-Smith takes the side of the censorious feminists who lost, and writes that she wants to abolish the entire sex industry, including pornography. I think the anecdote was included to give some kind historical precedent—and legitimacy—to the bitterness of the current discourse. But it reveals an annoying paradox in Lawford-Smith’s thinking. She wants to take up the mantle of the persecuted censored and the puritanical censor.

Still, she is willing to be challenged. I ask her if she can empathise with trans people who might feel vulnerable about highly public and combative debates about their fundamental rights, especially as they are likely to have experienced vilification, and maybe even physical violence, in a society filled with transphobia. I note that I am sceptical of the possibility of assuring a perfectly “safe” classroom—it’s obviously a critical ideal, but it’s something that is subjective, and difficult to pre-determine or promise. “But I do really empathise with people who feel like they’re caught up in an incredibly hostile debate,” I say. “What about the students who are experiencing that?”

“Why do they feel like that though? Victoria is a state that could not be any more trans friendly. It has all the laws that anyone anywhere in the world is aspiring to have,” she says. “This is a super-left, super-safe state, and a super-woke, ridiculous campus with inclusive Pride flags everywhere. They’re constantly rolling out policies to be as helpful as possible. One lecturer on the whole campus teaches one course that people have lied about, and now they're unsafe.”

Legislation and policy documents don’t necessarily mean that on-the-ground transphobia doesn’t exist though, I say. And discussions within the walls of the university aren’t isolated from the outside world.

“But what is the claim there?” she probes. “Of course there's discrimination against some people. Is the claim supposed to be like: if there wasn't the one left-wing feminist teaching about sex-based feminism, that trans person wouldn’t have got assaulted in a bar in Victoria?”

“No! I don’t think that.” My voice rises in irritation. I start to worry that I’m sounding like one of those dumb, hysterical feminists getting owned by Jordan Peterson in viral videos. I take a beat and reorient.

“I think the argument would be: sure, there is widespread social and legal acceptance in Victoria for trans rights, but there still is social non-acceptance from a not-insignificant portion of the population. Some of the debates that play out in public, around you as a public figure…people worry that this would come into the classroom. They find it hard to imagine your classroom as separate from those conversations.”

Here, the tenor of our discussion changes. I vacillated over whether to share some of the following statements—but ultimately I don’t want to sanitise Lawford-Smith’s position.

“If the thing they think is that ‘we have a right to be accepted as what we claim we are’ in a radical feminist class that is voluntary to take, then they will be unsafe. That's the disagreement, right?” she says. “I do not think any man has a right to me believing he's a woman. I am forced by the university to use his pronouns because we have a compelled speech policy. Of course, I will use them, because I'm not going to get fired for a stupid misdemeanour. But I don't think he's a woman.”

I ask where this animosity comes from—who is this imaginary trans person coming in and ruining her tute with their pronouns?

“It's not imaginary,” she says. “He’s been at many philosophy conferences. When a man comes in with terrible makeup, and declares that he's a woman, and everyone has to call him she, and he's peeing in my bathroom…”

“What if she’s totally gorgeous and her makeup is perfect and she’s wearing really stylish clothes?” I ask. Now I’m the one being disingenuous. It’s hard to know how to respond to this complete denial of the trans experience. Honestly, I’m confronted by it.

Our conversation reaches an impasse. We eye each other with not-insignificant unease across the cafe table. Is this what academic freedom and robust debate feels like? I can see why a trans student wouldn’t want to participate in Lawford-Smith’s class. Their ideas about gender are seriously irreconcilable. Which forces will be leveraged, and by who, such that one party gets what they want?

The conversation ends. I have to leave to go to a doctor’s appointment—I’m renewing my prescription for my contraceptive pill, a medical invention that probably changed the course of women’s rights as much as every piece of second wave literature combined.

Walking away, I wonder how Lawford-Smith sees me. Probably as brainwashed by the “trans ideology,” denying the material realities of sex, pretending that I don’t feel uncomfortable using all-gender bathrooms. I don’t. Perhaps she thinks my attention, as a feminist, has been drawn away from the issues that should matter, like domestic violence, sexual assault, and the devaluation of feminised labour.

In her book, Lawford-Smith writes that “sometimes moral disagreement is fundamental. It can happen that two people just can’t get beyond the fact that ultimately they disagree. Is disagreement about what gender is, and so what it means to be a woman, like this?”

If the practical outcomes of that disagreement mean that the vilification of gender-non-conforming people is seen as acceptable, struggling kids are blocked from receiving data-backed healthcare, my trans friends don’t feel safe using bathrooms, and whatever else the gender critical movement wants, then yes—this difference is fundamental. None of that has any bearing on my other feminist beliefs. Domestic violence shelters should receive more funding; young people need to be taught about consent and sexual pleasure; it’s a problem that the average Australian investment banker’s yearly salary is, on average, at least twice as much as the average nurse’s. Good faith dialogue with gender critical figures cannot take place when their positions are underpinned by a fundamental refusal to acknowledge that the trans experience is real and legitimate.

I walk back through the campus. Some students pose for photos in front of the “Wominjeka” sign on the John Medley building. Gum leaves pile up. I think about something Connell said that has stuck with me: “The image of gender studies and gender theory that's been created by the right-wing media…it's mostly fantasy. There's a huge amount of misrepresentation going on. And while critiquing and rejecting misrepresentation is important, the more important thing, I think, is to create something better.” There is a lot of theoretically flawless, mind-numbingly tedious work being done in feminism and gender studies today. But there is also good writing coming out of the discipline—I’m on the edge of my seat every time Long Chu publishes, and one of my uni friends at reckons that, after years of trying, she’s finally come up with a real, rock-solid critique of Judith Butler. Good things are happening too: from Monday, a coalition of staff who care about fighting for the ideal of the university will go on strike. They want, among other things, secure jobs, manageable workloads, and fair pay. These conditions contribute to making the university a more welcoming place, one where all kinds of students and teachers can participate in nuanced discussions about the history and future of our society—and about gender, too. Many of the classrooms I pass will be empty next week: ready for something better.