The Tote Autonomous Zone

What happens when a beloved rock pub needs saving—again? Cameron Hurst investigates.

Thursday evening, winter, the Tote rock‘n’roll bar. The front room is empty and stinks like sour beer and piss. The poster-plastered ceiling seems lower than usual. The carpet looks like it has a chronic skin condition. “Mama said there’ll be days like this,” sing the Shirelles over the speaker. “There’ll be days like this, my mama said.” A guy with tired eyes and long hair tucked under a beanie lumbers out from the store-room. VB tinnies are $11.50. I buy one and ask how things are going. Worse than usual, apparently. After last week’s drama, the bands have been pulling out. No bands, no punters. No cash flow. Which explains the painful beer prices…sort of.

Here’s what’s been happening: the current Tote owners, Jon Perring and Sam Crupi, are trying to sell the pub for market rate—$6–$6.6 million (devil numbers). Shane Hilton and Leanne Chance, the owners of another venue, The Last Chance Rock & Roll Bar, are trying to buy it. Since the sale was announced in March, they’ve crowd-funded $3 million and personally raised about the same amount to buy the building and turn it into a trust that will “legally protect the Tote from being anything other than a Live Music Venue for the rest of time.” No gastropub; no yuppie apartments. Instead, the plan is “giving the Tote to the bands of Melbourne forever.” Moving stuff.

The only problem is that Last Chance budgeted to buy the Tote for about $6 million. After the fundraiser Cinderella-slipped over the target at midnight, Perring and Crupi decided that they were actually still pretty keen on getting that extra $600,000 or so. “The current asking price allows for the mortgage, all liabilities and the current owners to be paid out fairly…as there is a shortfall between the community pledges, the Last Chance equity and the sale price, Governments (sic) and possibly private philanthropy would need to come on board to bridge the current gap,” they said in a post on the Tote’s Instagram the day after the fundraiser closed. Hadn’t these blokes done enough to deserve a punk retirement package?

The community feedback was a swift and ferocious, “No.” “This isn’t what the Tote is about…There’s someone looking down on this right now that we both know would not approve of this behaviour,” said one commentator. Whether that someone was God, Rowland S. Howard, or a secret third entity was anyone’s guess. But one thing was for sure. People were angry.

For now, negotiations continue. A “For Sale” sign remains above the Tote door. The bar is empty, until a single middle-aged guy in a denim jacket walks in and buys a beer.

“Got anything I can nibble on?” he asks.

“Nah, sorry,” the bartender says. “Run out of chips.”

*

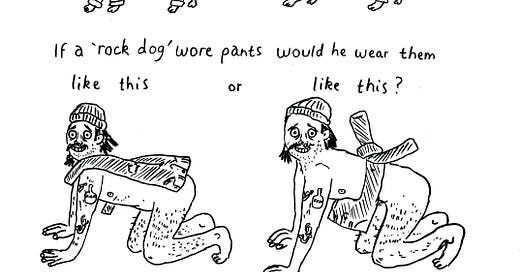

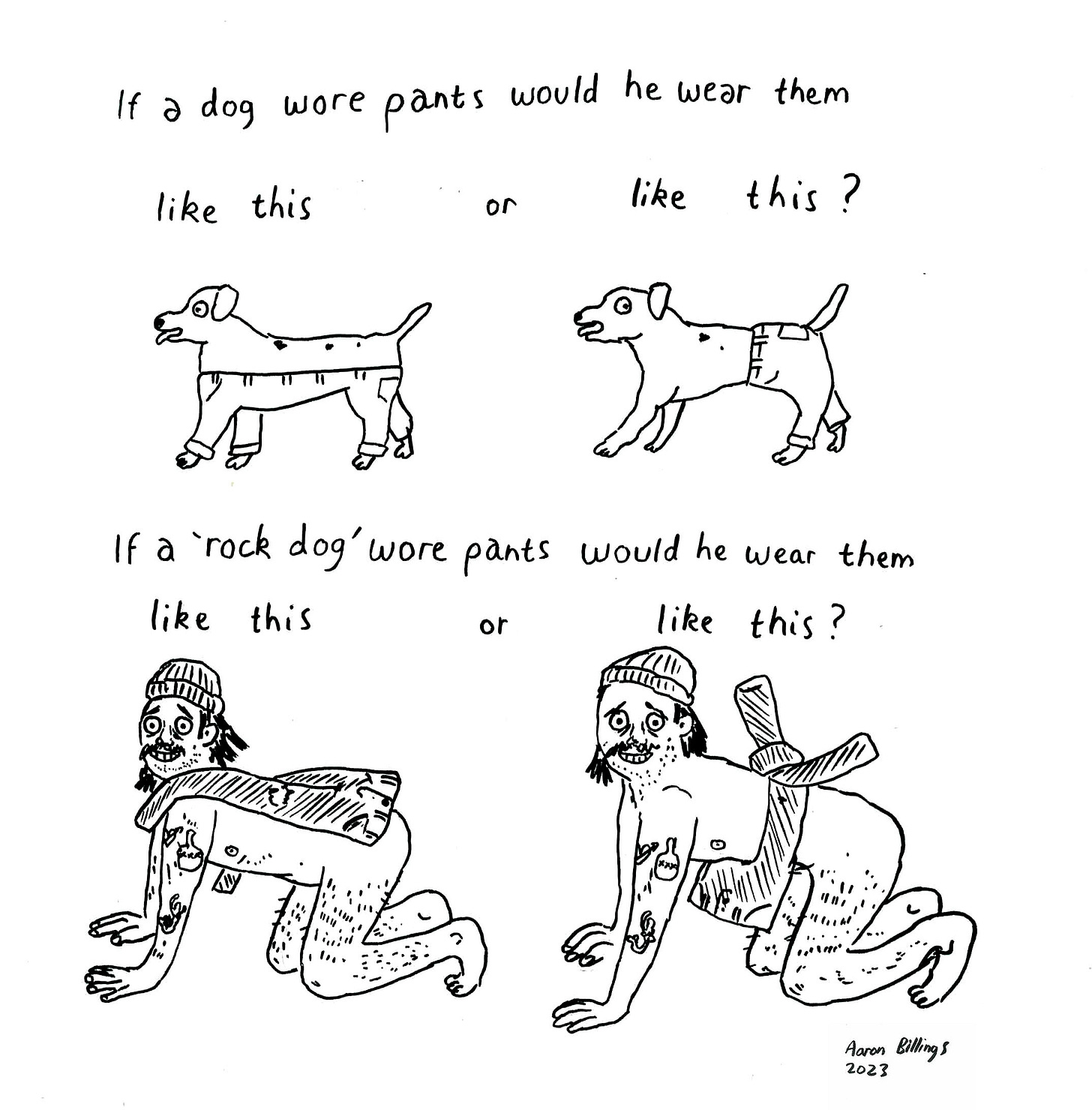

Some ungenerous questions went through my mind as I tuned into this situation: Should the Tote just be left to die in peace? Was it time for Melbourne rock‘n’roll to head towards the big pub in the sky? Why would people expect landlords of a fifty-year-old punk venue to be anything but punishers? And, more procedurally, if the Tote guys were always asking for $6.6 million (and it seems that, at least publicly, they were), why didn’t the Last Chance people try and crowdfund more money to begin with? I didn’t necessarily trust my own judgement—I’ve never been a real rock dog, only ever an occasional fan and housemate (aka audience filler) of rock dogs. So I spoke to a bunch of music people to find out: what the hell is actually going on with the Tote?

Nick Cave did not respond to requests for comment, so I contacted our second most important punk export: Brenna Olver, lead singer of the band Wet Kiss. Olver has a bleached ‘90s Courtney Love look, a sexy, churlish pout, and a droll demeanour. She used to work at the Tote; now she’s living Weimar-style in Berlin, working at another rock‘n’roll bar. She sends voice messages in response to my questions from inside the bar’s toilet. “There wouldn’t be a me without the Tote,” Olver says. “But there wouldn’t be a Tote without me.” Flushing sounds. What does she think about the quest to Save the Tote? “I was at the original Save the Tote campaign, just to observe the spectacle,” Olver says. “This is a repeating of history. We’ve already done this. As far as I’m concerned, it’s over.”

The protest Olver is referring to happened in 2010 and was organised by the Save Live Australia’s Music (SLAM) group. To get the backstory straight, I call Helen Marcou, who started SLAM with her partner Quincy McLean. Marcou is a rock matriarch with great lipstick sensibilities and a co-owner of the treasured Bakehouse Studios. She has an Order of Australia for her SLAM troubles.

“We didn’t save the Tote,” Marcou says. “The Tote was a catalyst for political action.” In the lead-up to the 2010 Victorian state election, there was a law-and-order crackdown. Politicians brought in strict new liquor licensing rules in a supposed attempt to curb alcohol-fuelled violence. New 3am licences were cut, and any venue hosting live music was considered “high risk” after 11pm. This meant that venues had to start paying for security. Some venues just stopped getting bands in, while others struggled under the new regulations. The first to close was the Tote, which, Marcou says, felt like an attack on live music culture. “They had this chequered but amazing history of nurturing young bands, so they became the poster child for the whole movement.”

This chequered history begins around 1870, when a settler named Daniel Healey built a two-storey Victorian hotel on the corner of Johnston St and Wellington St in the suburb of Collingwood—recently colonised Wurundjeri land. A few years later, it became the Ivanhoe Hotel. Throughout the twentieth century, Collingwood was a working-class suburb, and famously played host to the notorious gangster John Wren. The centre of Wren’s criminal empire was his "tote," a sly gambling operation. It was housed a few blocks down Johnston Street, but that whole end of town became associated with Wren's den. (The milieu was infamously represented in Frank Hardy’s 1950 novel Power Without Glory.) In the 1980s, in dubious homage, the Ivanhoe Hotel changed its name to The Tote, and also started hosting live music. For decades, Melbourne’s most successful and/or best bands would at some point almost inevitably play the Tote: Magic Dirt, Paul Kelly, The Dirty Three, Courtney Barnett, HTRK, Amyl and the Sniffers, Total Control, and, uh, Jet.

When the business crumpled after the liquor licence changes, there was an outpouring of community support. In January 2010, about 4000 people gathered outside the Tote to protest its closing. Then, in February 2010, an estimated 20,000 rallied outside Parliament House to protest the licensing changes more generally. These protests, along with a protracted lobbying campaign, worked. In October that year, the Victorian State Government revised the liquor licensing and made it easier for venues to host live music again.

The following year, Jon Perring, Sam Crupi, and Andy Portokallis took over the iconic pub from former licensee Bruce Milne. Records show they subsequently bought the venue from “Colonial Leisure Group” for $1 million in 2011. “In the eyes of the public, the Tote was saved,” Marcou says. But it wasn’t so simple. Portokallis died in 2018, leaving Perring and Crupi as the current co-owners. Sam Crupi has essentially no public presence; Jon Perring is the face of the business—he was a vocal figure during the liquor licence campaign. He’s a burly man with a white beard who is often photographed standing outside the Tote with a stern, beady-eyed expression. On his days off, he plays in a band called Slocombe’s Pussy. One notable release promises a psychedelic “Pussy Experience.” Dreamy. Nevertheless, there have been questions about the authenticity of their musical credentials. Olver caricatures the management vibes when she worked there as “cocaine and cowboy hats”: business and property guys with “no rock‘n’roll intention.”

*

Still, management did one thing right post-SLAM. They hired good people, who cultivated an environment where musicians from all genres and scenes played alongside one another. A new generation got to grow up in the venue during these golden years of polyphonic, poly-scenic experimentation, but of course, it didn’t last. Conversations I had with Tote-adjacent figures sketched a similar downward trajectory: wage theft scandals, general mismanagement, the pandemic, and a cultural turn towards electronic music.

The last gig I attended at the Tote was before Covid. It was a hot summer night in the upstairs bar. Various indie kids shuffled around, oversized shirts covering their beer-and-chop-shop bellies. Their benign slobbiness made what happened next all the more striking. The artist James Seedy strode on stage and started his support set. Seedy wore head-to-toe black latex, including a mask, and a cowboy hat that appeared hot pink under red stage lights refracting in a disco ball. He was accompanied by a laptop and a glossy black guitar. A lone ranger. Everyone in the room suddenly shuffled towards the stage and started doing those barely-nodding movements that pass for midweek musical enthusiasm in Melbourne. Women side-eyed each other, giggling, and angled themselves towards the artist’s glistening, oil-slick body. Seedy twanged his guitar and whispered into the mic through the hole in his mask. I’ll admit: I was horny for it.

Where is James Seedy now? He’s around. Early one winter afternoon, we meet at a cafe in Fitzroy North. Off-stage, Seedy is softly-spoken, with wide eyes and bleached hair growing out at the roots. He’s studying sound production, hoping to get more commercially-viable work as a musician. Turns out being the scene’s sexiest neon latex cowboy doesn’t quite pay the bills. But he is dedicated. He has been in bands on and off since he was about seventeen and can’t imagine doing anything else long-term. What does he think about the Tote situation? Despite playing countless gigs there, and fondly remembering a time when he spent practically every day hanging out with the bar staff during a brief period of unemployment, he hasn’t played a show at the venue for ages. This wasn’t necessarily a conscious choice. Lots of musicians have been semi-boycotting the venue for the past few years. “It wasn’t a very outspoken boycott,” he says. “The Tote right now is just not that loved in the community, especially after all the super stuff came to light.”

The super stuff: Jon Perring and co., who own the Tote (and Bar Open and, previously, Yah Yahs, among other venues), have been caught out for wage theft multiple times. Staff members made claims for years of underpayment in a high-profile stoush in 2013. Andy Portokallis, the owner who passed away, infamously reply-all emailed an underpaid former staff member and her lawyer, saying “K*nts!” In 2020, it came out that more staff were missing more payments from the intervening years. Perring called media coverage of the underpayments “sensationalist,” “false,” and “opportunistic reporting”; the Tote’s website says that all outstanding super has now been paid out. (Rumour has it that Perring occasionally addresses people as “comrade,” which, given these circumstances, some in his orbit have found galling.) After the most recent wage theft debacle, beloved Tote staff began to call it quits. Brenna Olver confirmed: “The owners were infamous for not paying super…not that I care about that. I withdrew it all in Covid.”

Other more fiscally conservative punks began opting to play elsewhere. But the soft boycott didn’t mean that people had given up on the Tote entirely. Isobel D’Cruz is a classically trained musician who used to play in a post-punk band and is currently writing an ethnomusicology thesis about race in Melbourne alternative music scenes. She has tousled, curly brown hair, a warm smile, and, on the morning we rendezvous at Cathedral Coffee, wears an oversized jacket that she suddenly realises her boyfriend has left his car keys in. Oops. That’s a problem for later. We sit down and start talking Tote. Does she think it’s worth saving? I half want her to go polemic and say that it’s an irredeemably old white punk zone that should burn to the ground. She doesn’t.

“I feel personally invested in the Tote,” D’Cruz says. “It was always in my mind as a cool place when I was growing up, because when my mom moved here from Malaysia in the ‘70s, that's where she was seeing bands.” She’d donated to the Last Chance campaign. But D’Cruz notes that she’d heard criticisms of the crowdfunding from people she respected. Some were angry that, during a cost-of-living crisis and a period of rising inequality, $3 million could be dredged up for a pub, but not more meaningful mutual aid. It was an understandable sticking point, especially when much of the money raised would go to paying off the current owners’ private business debts. Ultimately, though, she’d come to feel that the two options didn't need to be mutually exclusive. People could Pay the Rent and Save the Tote.

Also, the value of the Tote to the community couldn’t be underestimated. For D’Cruz, the venue was a place to connect with a diverse array of genuine music nerds. At least, it had been. “It was where I sort of met all of the people that I first started playing music with. It's where I launched my first EP with my old band,” D’Cruz says. “During that time [around 2016-2019], the Tote felt like this really progressive place and not in a superficial ‘we tick all the boxes’ way. Some people now find the Tote whatever because it just seems like such a rock dog, boring kind of thing. But I felt like there was a period where it wasn't that.”

One reason for the shift seems to be music styles cycling in and out of favour. We speak about the cultural pendulum swinging firmly towards the electronic. This development was accelerated by the pandemic’s long lockdowns—bands need the alchemy of real-life interaction, and it’s easier and cheaper for venues to book DJs. Indie sleaze revival notwithstanding, it’s less cool than it once was to be a rock star. DJ hegemony is real.

D’Cruz and I agree that there is no objectively better style of music—it’s a matter of taste, and perhaps day of the week—but that DJ-world has a notably different set of cultural norms to live-music-world. This can be prohibitive to entry; the cost of natural wines and oysters and vinyl and/or CDJs and salon-bleached hair and micro-designer rags can really add up, and these purchases don’t even guarantee that someone will hug you at Miscellania, let alone put you on their kick-ons Instagram story or, God forbid, book you for a party.

“I've always been struck by how much having money is glorified in those scenes,” D’Cruz says ruefully. “In saying that, I know that the criticism with guitar music is that people were trying to look poor. But I also think that it's easier to go in [to venues like the Tote] as an outsider and not necessarily be visible. I just know so many, like, genuine punks—misfits in a self-identified way—who feel like they can go to these venues and feel alright.”

Multiple people I spoke to singled out a guy named Rich Stanley as a driving force behind the Tote’s glow-up period. In 2013, Stanley, a genial bloke who’d been playing in rock bands for decades, started working as the venue’s booker. Stanley phoned in from a family holiday in Osaka to chat. He’s got a relaxed drawl, an even-handed manner, and a reputation for being fastidiously organised. His role put him at the centre of the Tote cyclone, tasked with mediating between all the different aesthetics, politics, and musical personalities that tore through the building. “I tried to make it so that you could have, on the one night, some disco, some slacker pop bands, indie rock bands, and some metal bands, whatever,” Stanley says.

One challenge was balancing the desire for diversity without forcing very different scenes into the literal same room. “Ultimately, does a doom metal band want to play with some kids with synthesisers?” Stanley says. “And, just as importantly, do the kids with synthesisers want to play with the doom metal bands?” He supported progressive politics, but his job also required a pragmatic approach. There were friction points. As the 2010s ticked over, Stanley was sometimes frustrated by what he saw as a lack of tolerance shown by new punters. He expressed this with a sense of lighthearted pathos.

“Previously, the Tote had been a place where you could go to when you were a daggy fucking rocker who had no idea about fashion, no idea about trends. It didn't matter,” Stanley says. “You went to the Tote, and no one gave a fuck if your clothes didn't fit, if they were unwashed for two weeks. No one was ever going to look down their nose at you.” Suddenly, the Tote was cool. It had become a high-profile venue that everyone wanted to play at. Pretty much everyone I spoke to agreed that this was a high point of Tote history, and that a key reason why was the multi-genre programming. But the increased prominence also had negative effects.

“All of a sudden, all these daggy rockers were sitting at the bar, and there was someone talking about inclusivity who was actually making them feel unwelcome,” Stanley says. “People who often had good university educations were looking down their noses at people who were just as intelligent as them but hadn’t had that privilege.” Listening to Stanley, I sensed that he’d been hurt by these interactions too—felt that he was also being looked down upon. It wasn’t catastrophic; he dealt with it. But there was one thing that still irked him when he thought back to that era. “All these electronic artists were coming in trying to cancel the metalheads, but they were using death metal style logos on their artwork. It was like, full cultural appropriation!” he says, laughing. (It must be noted that plenty of misfits and weirdos thrive at free underpass donk raves and get by on scalp-searing Chemist Warehouse box bleach jobs.) Stanley’s tenure ended during the pandemic: two major blows to the Tote’s health. Overall, though, he was happy he’d worked hard to “smash the rock rock rock thing wide open.”

*

“The thing about the Tote is that the Tote is a church,” says Wet Kiss songstress Brenna Olver. “Everybody wants to go to church. Everybody wants a sense of belonging. People long for somewhere to pray. But much like other churches, the leaders have been corrupt.”

After years of neglect, the building is notoriously decayed. “At this point in my life, I don’t really want to go places where I need a plastic bag to sit down,” Helen Marcou says. “I want a Campari soda and a nice stool.” Fair enough. Punters who aren’t leaning into the ironic bourgeois retired punk bit also have complaints. One person I spoke to remembers playing a gig where bar staff patched up a roof leak over the stage, which was covered with electrical equipment, with sodden tea towels. Another person told me they knew someone who moshed in the front bar and cracked his head open on a fan. He reckons the blood sprayed onto the roof is still there. Even if these rumours aren’t true, I have my own harrowing memories from my late teens of spewing, hideously drunk and stoned, into a filthy downstairs toilet and, as I came up for air, feeling like I had been transported straight into the cubicle from Trainspotting. What kind of naive, amazing lunatics would take on the responsibility of a multi-million-dollar crowdfunding campaign to save this pile of heritage-listed Edwardian punk rot?

Shane Hilton and Leanne Chance, of The Last Chance Rock & Roll Bar, are a classic rock dog couple. He’s got a grizzly, gingerish beard and has been getting campaign donors’ names tattooed on his body. She’s gorgeous, has jet-black hair, and is also tattooed, although with less fraught content. They seem made for each other. In 2016, the pair took over a bar on a corner opposite the Queen Vic Markets in North Melbourne. Last Chance is decorated with memorably ugly Victorian wallpaper and has objects pinned on every surface: guitars, Converse sneakers, skateboards, a “Chiko Moll” shirt, gig posters, and hundreds of Polaroid photos of Hilton, Chance, and various punters holding half-drunk pints and giving the rude finger. The pool table is fresh and green and there are good snack deals. The bathrooms are covered with band stickers and have black duct-taped mirrors, but the floors have been mopped recently. Many bands avoiding the Tote play at Last Chance instead.

Hilton and Chance continued to run the bar while coordinating the Save the Tote crowdfunding campaign, and presumably remortgaging their every asset. The campaign closed at $3,097,749. Just over the finish line… until it wasn’t quite.

None of the major protagonists in this story—Perring, Crupi, Hilton, or Chance—responded to my requests for an interview. After the PR disaster of the Tote’s Instagram post, all have gone quiet about specifics as the real negotiations get underway. Occasional public updates are to the tune of “discussions are ongoing.” Crowdfunding contributions have begun to be deducted from contributors’ accounts, though. And so everyone waits with bated breath. Will the sale go through?

“I really, really hope so. I think it’s going to happen,” Seedy says.

“I don't think the aesthetics of Last Chance are, like, my favourite aesthetics,” D’Cruz says. “But Shane and Leanne seem really nice, and everybody putting in financially or even just energetically is a chance for the Tote to be built by the community.”

Stanley wasn’t surprised that the Tote initially knocked back the Last Chance bid. “Classic Perring move,” he says. “Agree on an outcome but when the time comes, question the validity of the whole thing and move the financial goalposts.” Still, he’s confident that Hilton and Chance will get it through in the end.

After Stanley left the Tote, he got a job at the Collingwood Children’s Farm, an idyllic (from afar, at least) non-profit organisation—think sheep, scones with jam and cream, and children frolicking on the banks of the Yarra River. Going through a period of Covid-induced reflection and working in the community sector, he felt increasingly disillusioned with the “private capital that controls the institutions we rely on.”

“I’m keen on this public trust idea,” he says. “I’d like to see the Tote run as a not-for-profit, managed by a committee, with roles given four-to-five-year limits. There’s also heaps that can be done with it during the day for mob and young people, building capacity and community, as they like to say.”

They do like to say. Will they like to do, if they get the chance? Is it possible that the Tote is about to become a radical piece of collectively owned community infrastructure? Are we about to witness the birth of the Tote Temporary Autonomous Zone? All that energy. All that hope. I think I’m ready to mosh again. Utopia seems within reach…as long as the roof doesn’t cave in. Let a thousand more pints spill on the band room floor. Let a new generation of pups grow into full-blown rock mongrels. Let the true spirit of rock‘n’roll return to the building. Save the Tote!