The Nicholas Building (Sandwich) Artists Are Under Threat

Sally Olds investigates the rent raise turmoil: who will stay and who will go?

On my final night in the Nicholas Building, I attended a histrionic wake for my twelve-person shared studio. A month before, in late January, we had received word that the rent raises—which we had fended off since late 2022, and which would nearly double our monthly payments—were final and irrevocable, and that if we couldn’t or wouldn’t pay, we had to get out. We were getting out. Past and present studio-mates sat on the floor drinking champagne out of filched 7/11 coffee cups. In my two-year tenure, the floor in question—black-and-white lino embedded with decades of grime and paint—had been impossible to truly clean. I wandered forlornly around with a broom, sliding dust from one corner to another. A 40-something-year-old stranger arrived, wearing a parachute suit and pink plastic sunglasses, lugging a six-pack of giant beer cans (it seems to be a rule of the universe that every maudlin party is attended by just such a character). The mood was one of serious drinking. Cigarettes were ashed directly onto lino. I sat in the window sill, legs over Swanston Street, gazing at St Paul’s Cathedral. All over the building, outgoing-tenants rolled their desk chairs into lifts. A friend on level nine sent me videos of himself flailing through the corridors, tearing down posters I’d put up trying to sell my furniture. A tenant on level three, referring to the property manager who had overseen the process with demonic indifference, spat through a thick French accent: “she is piece of shit.” There was nothing much left to say. It was over. I went home. I took to my bed and festered.

*

The Nicholas Building is a 10-storey chunk of concrete near Flinders Street Station in Melbourne City. The facade is decorated by Doric columns and other period flourishes, and tiled in fake granite that, in various lights and at different times of day, appears white, grey, or pale orange. The arcade on the ground-floor has a curving, vaulted-glass ceiling like the underside of a leadlight lamp shade. In the centre of the building there is a light-well, running from the first floor to the rooftop. On each floor, there are two rings of studios: one has windows onto the light-well; the other, across the corridor, has windows over the city streets. There are around 100 rooms within these rings. The rooms are gorgeous: grand and shabby, with soaring ceilings. In the last thirty years, the majority of these spaces have been occupied by artists, writers, and craftspeople of all kinds.

When writing about the Nicholas Building, which many have done, it is customary to begin with a potted history of the building’s genesis (a monument to the Aspro Clear brothers’ fortune, built in the 1920s), before moving onto a nostalgic summary of its recent past (the rag-trade, the lift operators, the button merchants), leading into a survey of present inhabitants, all of them quirky and loveable, all of them capital-I Individuals (the Peruvian tailor, the Joseph Beuys guy, Vali Myers). These pieces invariably end in speculation as to the building’s uncertain future as an artists’ haven. And, just as each generation imagines that the end of the world will happen in their lifetime, every recent generation of Nicholas Building renters imagines that the Nicholas Building will end during their tenancy. In 2010, the rent was going up, the artists moving out. In 2013, same thing. In 2022, danger peaked when the property was put on the market for $80 million. The council was going to buy it, then didn’t. The State Government was going to buy it, then didn’t. An altruistic property-investing firm (hmm...) was going to buy it, then didn’t. Then the owners—four deep-pocketed Toorak families—raised the rents, and many of its occupants were compelled to leave, including me.

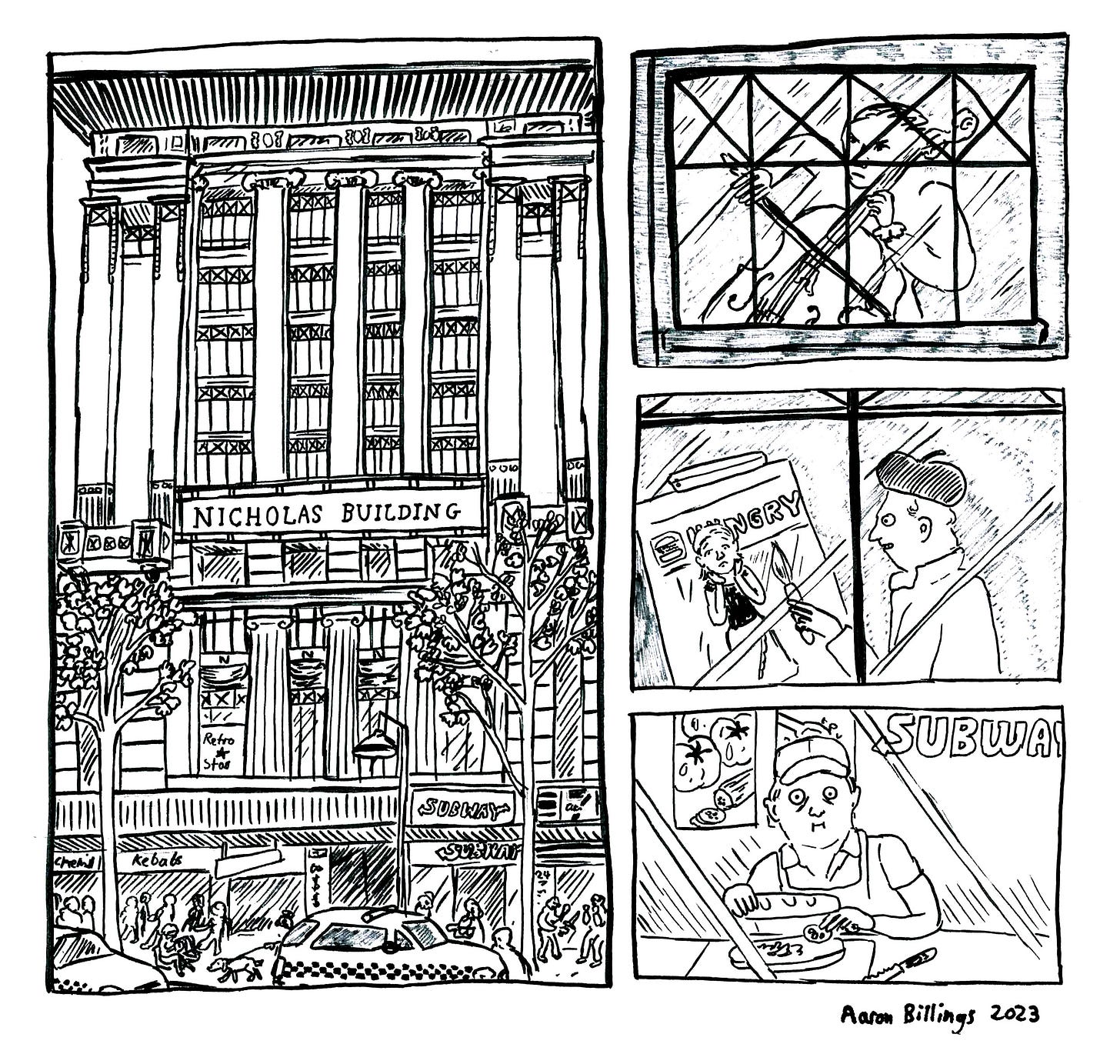

No offence, but this story is all a little Wes Anderson. Imagine a movie camera panning across the facade before zooming in on a lit window, behind which an eccentric older gent practises the cello, and then in another window (zoom out, zoom in), a woman dabs her paintbrush onto her palette, and then (zoom out, zoom in), a jeweller shapes a piece of molten metal. I’m not saying it’s not a charmed, vertical village powered by artists and artisans. I am charmed by it; I am committed to the lore. But there's something missing from this picture. Everyone forgets about the other tenants. If the artists are the building’s beating heart, then the building’s gut—the churning, toiling, money-making core—are the businesses.

The Nicholas Building’s ground floor and basement level began as a Coles, and the street-facing areas are still taken up by commercial leases: a 7/11, a Subway, a pizza/kebab shop called Tasty, and Arthur Daley’s, a bargain basement everything-shop that pumps lo-fi classical music into its stairwell. There is also RetroStar, the booming vintage store on level two that injects a steady stream of thrift-hungry teens into the stairwells. The commercial tenants represent one possible path for the Nicholas Building. From ashes to ashes, dust to dust…Coles to Coles? It may return from whence it came, into the hands of the merchant class, the artists a brief blip in its history. I have heard from reliable sources that the owners want to keep the building as a community and artist hub—apparently, they even turned down a Singaporean hotel chain who made an offer when it first went to market. But the businesses are also how the owners bring in money from the building, charging astronomical rents for street-frontage, which functions as a form of subsidy for the relative pittance of studio rents. (One of the smaller ground-floor shops costs nearly $40,000 per month to rent—and this is pre-rent-hike. In comparison, the new rent on my old studio, a veritable palace at 82 square metres, is around $37,000 for the whole year.) The fates of the artists and the vendors are tied together, but in your typical Nicholas Building lamentation, nobody thinks to check in on the businesses. Having spent most of my adult life talking to artists, and certainly most of my stint in the building, I figured it was time to cross the divide. Plus, I really wanted a Subway cookie.

At each establishment, staff friendliness bears an inverse relationship to commercial viability. The most dismissive—and probably the most viable—are 7/11, though admittedly I tried to introduce myself to the owner during a lunch-hour rush (this, I’ve observed, is the only time he comes in). He tells me they have been negotiating with the agents, but that he hasn’t been the one to do it and can’t give me much information. A group of tradies are pressing up against me wielding Mothers and plastic-wrapped pies. I leave my name and number and get out of there.

Subway is next. The first guy I speak to is in the middle of making a meatball sub when I ask about the rent hikes. He says the same thing as 7/11: that negotiations are taking place and that he thinks it’s been a long process. He makes a lot of hand gestures and moves his lips around, indicating trouble. He slides the sub along the counter, smiles apologetically, and tells me that’s all he knows.

When I return to Subway that evening, the friendly worker has knocked off, swapped out for a stern young woman with tightly-plaited blonde pigtails poking out from under her green cap. I ask again about the owner, and she tells me that she is not at liberty to give out his contact details, and I reassure her that I’m not asking for them, and she glares at me. I duck across to Cathedral. Cathedral is a ground-floor cafe hotspot named after St Paul’s. It has replaced Neapoli and Meyers Place as the artist haunt in the city, and on any given night you may find at its tiny round tables many of this building’s tenants, plus six-figure salaried curators, famous novelists, employment lawyers, philosophy tutors, dole-bludging sound artists, and, sometimes, the editors of this newsletter. The cafe also hosts Cathedral Cabinet, a kind of miniature art gallery, which consists of a single, large window that displays new artworks, rotated every month or so. In an amusing twist of architectural fate, Cathedral faces Subway’s internal windows, so that even as you enjoy a plate of Mount Martha mussels and a glass of Moopie-produced rosé, you may be sitting directly opposite a haunted-looking suburban dad wolfing down a 12-inch seafood sub.

When I look up, the sandwich-artist is staring at me. I get up to inspect the artworks in the window: two black-and white text pieces by Angela Nolan and Gemma Topliss. They are scribbly, blown-out, staticky, cute. I’m into them. But there’s no escaping Subway, even with my back turned. Tonight, as always, the green-and-yellow Subway logo reflects off the glass. It hovers over Nolan’s work, disrupting the text, which says ‘dodgy’ over and over again.

7/11 and Subway can probably afford to cop the new rent. And, as giant, well-resourced multinationals, they may also be able to negotiate a better deal. The most likely to be wrecked by the raises are the pizza/kebab shop and Arthur Daley’s. When I return the next day to talk to them, both proprietors are very sweet. I get the sense that this is partly because they have been dealing with the real estate agents directly, unshielded by parent corporations—that for them, it’s personal.

At Tasty, the pizza/kebab shop, I say: “Can I ask you a question?” The guy answers: “Can you order something first? And then I’ll tell you what you want to know.” But before I can nab a slice of pepperoni pizza, he calls out the back for the owner. I wait at one of the laminated-wooden tables. The shop is a typical city fast food joint, with a glass case of pizza and a bain-marie for kebab components. The owner comes out and shakes my hand. He has a closely-cropped beard and is just slightly taller than I am, in his late thirties or early forties. His rent is about to be raised, though he doesn’t say by how much, and he will probably have to leave before it kicks in; the jump in cost will be too much to absorb. He used to manage a Hungry Jack’s, and tells me he still has access to deep HJ intel—he has heard they may want the space. Meanwhile, he was told that his own business “doesn’t fit the profile of the building.”

“This shop is my whole livelihood,” he says. “In six months, I’ll have to leave. In the seventh month, I don’t know how I’m going to feed my family.”

On my way out, I order a slice of pepperoni pizza. The guy at the counter hands it over and waves off my attempts to pay for it. “Next time you come in,” he says.

At Arthur Daley’s, I walk down the stairs, past the iconic wall of CCTV printouts displaying thieves caught in the act, and up to the electronics counter. The manager, Leslie, takes me into an aisle crammed with dusty trinkets. She does not want to talk about the rent situation (at least, not on the record) so instead we talk about her last few years in the city. She has had a tough run. First there were the COVID lockdowns, and now there’s the Metro tunnel works, which have been noisy and dirty, with dust flying into the shop through its street-level opening and leaks sprung in the walls and ceiling. Post-lockdown, mid-recession, the city has changed, too. She observes that many pedestrians are empty-handed: no shopping-bags. People will come into the city and have a drink, she says, but they won’t buy anything.

On my way out, I have a poke around the store. Arthur Daley’s sells everything from plastic penis straws to miniature Australian flags to bedsheets to power cords. Losing Arthur Daley’s is probably not of the same order of sorrow as losing 100 artist studios—and sure, the entire enterprise is probably morally indefensible at this stage of environmental collapse. But I happen to know of at least one famed city cafe that buys all their tableware from Arthur Daley’s. Art students, schooled just across the river at the VCA, are likely making work that contains Arthur Daley’s materials. If you were or are a teen in Melbourne, you have probably walked your Boost juice down from RetroStar through Arthur Daley’s aisles of Halloween masks and scented candles. And my favourite ever shirt is from Arthur Daley’s: a perfect plain grey tee with a ribbed collar, the fabric both firm and stretchy, like al dente pasta. I can’t help it. I feel sad that it might close.

I also feel weird about feeling sad. What does it mean that I’m nostalgic for what is, essentially, a two-dollar shop? Shouldn’t I be mourning the loss of Melbourne’s "laneway culture" instead? But Arthur Daley’s means something different. As surely as Q-bar or Dangerfield, it is a reminder of a different era in the city, and of a less sophisticated phase of commerce. If it was once a grossly acquisitive eyesore, nowadays, it is far from the most rapacious capitalist on the block. There is always a bigger fish, and it’s disturbing to catch it in the act of devouring a prior adversary. I imagine a future Sally Olds, ten years from now, hovering outside the Nicholas Building, grappling with the mixed emotions provoked by the shuttering of the grim but pleasantly familiar Hungry Jack’s.

*

The best hope for the building comes from inside. The Nicholas Building Association, a coalition of tenants who first got together in 2017 to push back against an earlier round of rent hikes, are a highly-organised bloc with a utopian vision. At the time of writing, the owners still want to sell for $80 million. The NBA’s ultimate goal is to buy the building—raising funds through public programs, philanthropy, maybe a bar—and keep it permanently in the hands of the community: cheap rent forever! No longer functioning as the building’s sacrificial cash cow, the businesses would likely benefit too (though whether there is a place for 7/11 in this utopia is up for debate; frankly, retaining the option for $2 coffees would be nice).

The building’s property managers, the real estate firm Gorman Allard Shelton, have their story and they’re sticking to it: the new rents simply reflect the market value of a prime, heritage-listed CBD location. They have pegged this amount at $450 per square metre per year, though some spaces are renting for more. Tenants on “legacy rates,” rents that are below $450 and have been for years, are merely being ushered into the 21st century (with the added benefit, for the owners and agents, of bringing the building’s overall value closer to that 80 mill asking price). For some, this has meant a 100% rent hike. This valuation is based on other buildings in the city, for example, the Block Arcade on Collins St, which is also managed by Gorman Allard Shelton. But the Block Arcade is a pristine, lovingly maintained slab of Melbourne nostalgia, with stained-glass windows and kitchenettes on every floor. By contrast, most studios in the Nicholas Building have flaking paint, permanent leaks, and no running water. To get water, you have to go to the bathrooms (there’s one between every floor) and fill your vessels at the toilet sinks. Anyone who has ever used these amenities knows the “market value” line is a brazen lie.

“In the bathroom on this floor,” a friend on level seven tells me, “there is a pube sitting on top of one of the urinals, and it’s been there ever since I first came to the building.”

I’m not surprised—once, on level three, an unmentionable blockage in one of the toilets caused months of havoc—though I am a little put out. Outlasted by a pube, I think. At least it’s a historic pube…It might have been there since the 90s! It might have belonged to Gregory David Roberts! As I ride back down in the lift, I feel cheered by this thought. Amid the hollow real estate spin, the pube is a welcome intrusion of reality, and a heartening symbol of…what, exactly? Human resilience, the unstoppable tide of filth, the anthropomorphic potential of built environments? It means something, anyway. And downstairs, on the embattled ground floor, things seem a little rosier. Pouty girls, rumpled grad students, and walking-tour grandmas still convene over orange wines at Cathedral. Mangled pigeons still fight over cigarette butts outside. I settle in with the Moopie rosé (it’s delicious, honestly) and feel a sensation of warmth spread across my body. I am on high alert for graphic designers, who I imagine are taking over the building, but not even when a few men in ironed chinos and sneakers walk by am I shaken from my calm. The pube is fixed in my mind like a talisman. I picture it as a coiled spring, taut with latent energy, ready to unfurl into the future.