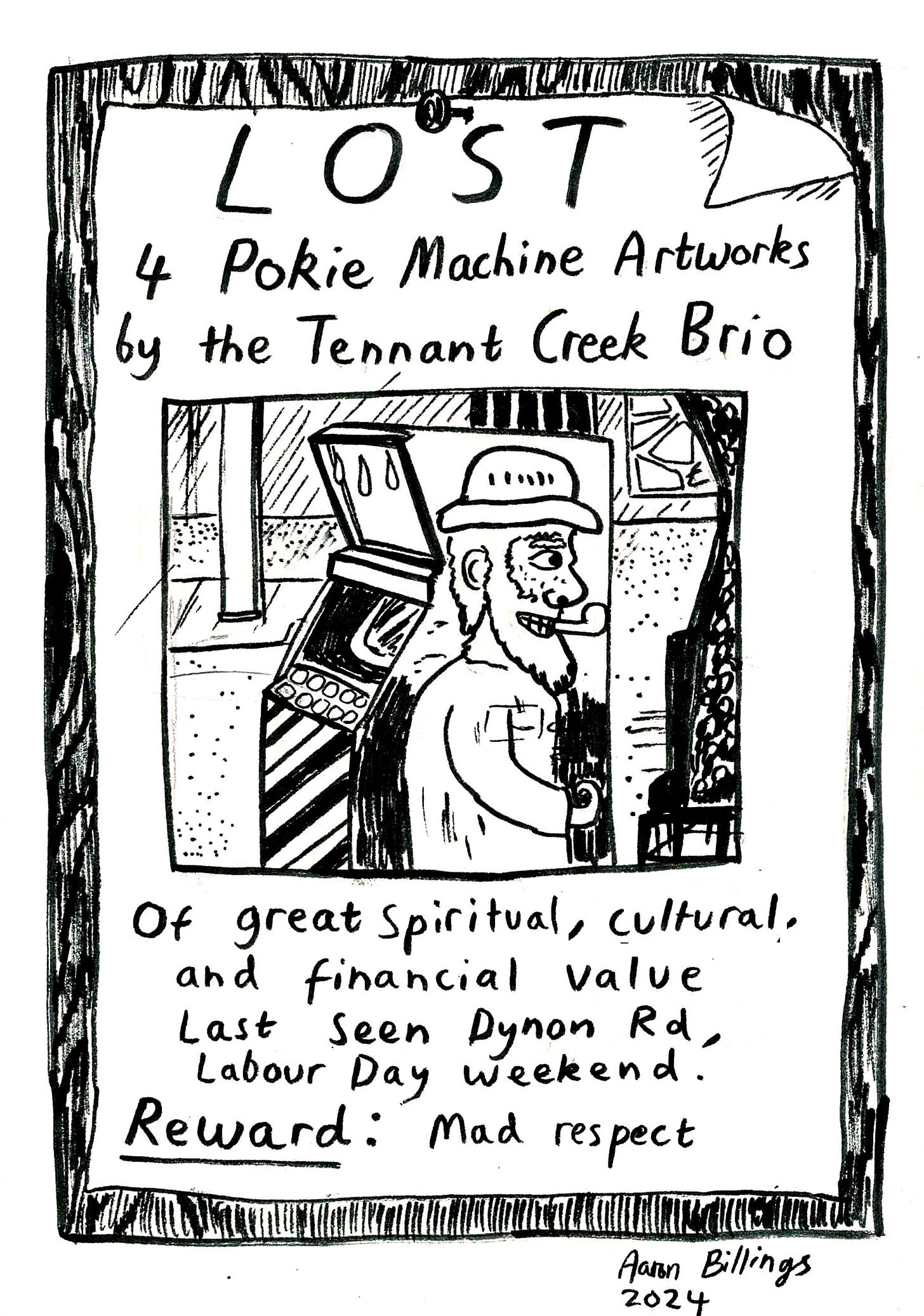

The Case of the Stolen Pokies

Four artworks by the Tennant Creek Brio disappeared from a warehouse in West Melbourne. TPE is hot on the trail.

On 10 April, we received an unexpected message from a friend, Lévi McLean. He said he had a story for us: an art heist, possibly involving a rave. At some point on the feverishly hot Labour Day weekend just past, four artworks went missing from a warehouse in a dusty industrial pocket of West Melbourne, right next to a well-known party spot. The artworks were by the Tennant Creek Brio, a lauded art collective from Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory, a small town on Warumungu Country. The works were adapted found objects: pokie machines painted with symbols—dots, a stockman, slashes of bright white spray paint, fuzzy around the edges—and phrases like “we need rain/ the Country's in pain.” New additions conversed with the still-visible original designs, like a set of twisting-tailed dragons with bared fangs. Not only were the works key early Brio productions (some were exhibited to acclaim at the 2020 Sydney Biennale, NIRIN), but they were going to be shown at the group’s major upcoming show at ACCA, one of Melbourne’s most prestigious public contemporary art galleries. None were insured, and besides, they were pretty much irreplaceable. Who the hell racked these gonzo desert Duchamps? The Paris End had to investigate.

We called up Lévi first. He had a long list of potential suspects: “Extremist ‘No’ voters who wanted to take down a symbol they found threatening. Misguided patriots. Delinquent anarchists. Maybe pokie machine lobbyists. Or even anti-pokie machine lobbyists, who wanted to destroy them. Puritans. A rival collective. Or, maybe, it was a bit of brinkmanship and horseplay between some ravers. Jackass types.”

Lévi is an artist and charismatic member of an Australian art history family. In 2019, he moved from Perth to Tennant Creek, began working with the Brio, and ended up writing a thesis on the collective. The group started out in 2016 as an offshoot of a men’s art therapy program run at a local health centre. In 2018, Nyinkka Nyunyu Art & Culture Centre director, Erica Izett, came across a shed full of the singularly bombastic art that the men had produced in the program, and called up a mate to organise an official exhibition. They decided on a collective name, and thus the “Brio”—an Italian word meaning “fire, mettle, style,” a kind of performance—was born.

Their first show was a huge success, and almost immediately, the group received a surge of interest. Initially, Brio members were men from the Warumungu, Warlmanpa, Warlpiri, Kaytetye and Alyawarr language groups, as well as one white artist from Melbourne. Core artists now include Fabian Brown Japaljarri, Rupert Betheras, Marcus Camphoo Kemarre, Jimmy Frank Juppurla, Lindsay Nelson Jakamarra, Clifford Thompson Japaljarri, and Joseph Williams Jangarrayi. Recently, siblings Eleanor Jawurlng and Arthur Jalyirri Dixon started working with the group. Lévi, who also makes films with the collective, described his role in the Brio as: “An emissary of sorts. One of the Brio delegates, an arts worker, and a regular art world bureaucrat.” He's helping organise logistics for the ACCA show, for example.

It’s a shifting coalition, where artists have a fair bit of independence to work on their own projects, then exhibit all together. Brio members work in wildly different styles, although they frequently collaborate. The group’s work often depicts culturally significant symbols and texts alongside commentary on the impacts of colonialism, historically and in the present, on the region around Tennant Creek. The Brio frequently utilises found objects, such as masonite boards, mining maps, and busted pieces of technology. “We are really re-enactments of BC ancestral beings, we are the living history,” as a phrase painted on an old TV exhibited at NIRIN put it.

Jessyca Hutchens, a Palyku woman and university lecturer at the University of Western Australia, was Curatorial Assistant at NIRIN, where the pokies were first exhibited. She recalled that the Brio’s works were like a magnet; people wanted to be around them. “I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this before in Australia,” she told us. “It’s spirited. It’s very rock ‘n’ roll. It’s just cool.” She was sad to hear that the pokies are missing, but added: “They have a life of their own. When the Brio did one of the pokies for Black Sky [an exhibition Hutchens curated in 2023], they were getting materials out of an e-waste bin from here on campus and continuing to add to it before the show opened. They just have that way of picking up cultural material and rolling it in.” When—if—the pokies come back, what will they have picked up along the way?

We spoke to one of the Brio's founding members, Joseph Williams, to hear his thoughts on the heist. Joseph also goes by “Yugi” (meaning Yugoslavian—his dad’s Croatian; his mum's Warumungu). Joseph had contributed to the making of the stolen artworks. Each one was a decommissioned poker machine, salvaged by Brio member Rupert Betheras from an abandoned local nightclub, Shaft. The machines were gutted and painted over with colourful patterns and figures. Joseph remembered painting the lines about rain—the region was going through a drought at the time. How did he feel when he heard about the theft?

“I was a little bit upset,” Joseph said. “They were shown at the Biennale, of course, and a lot of people had seen them. And we’d put in a lot of work.”

Still, it wasn't like the pilfering had consumed Joseph’s life in Tennant Creek. He'd been busy making new works, some with faces and designs that represented spirits from his home.

“In my language, we call those spirits Ngurramala,” he told us. “They're the locals that live on the Country all the time, for the rest of days. We can't really see them, but we can hear them and we can feel them. Sometimes visitors go on Country, damaging sites or cutting down trees without speaking the language from that country to them. Without telling them what you're doing... obviously, you're going to need to speak warrakajji, from the area I come from, to those watchers. I call Ngurramala the ‘watchers,’ because they're watching us all the time. Making sure we’re doing the right things out bush, not mucking around.”

Lévi and Joseph joked about how they wished the watchers had been looking over the West Melbourne warehouse. Did the pair have any more theories about who could have nabbed the artworks?

Joseph said he wasn't too sure. Then an idea struck him. “They could be the grandkids or the sons of the people that designed the poker machines.” Cha-ching! The house always wins?

As for Lévi, he’d been doing research into historic heists, going deep into the 1911 theft of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa from the Louvre, trying to reconstruct the psychology of an art thief. Louis Lépine, the detective on the Mona Lisa case, was thwarted for years, wrongfully suspecting figures in the French literary and artistic scenes, including, at one point, Pablo Picasso. But the real culprit, Vincenzo Peruggia, was an Italian labourer who had stolen the painting for patriotic and/or financial reasons. There was a lesson to be learned from the Mona Lisa affair: we shouldn't assume anything about the potential thief. “The person might not be an art world aficionado who's out to get us. They might not want to resell the works,” Lévi said. He semi-ironically quoted a line often misattributed to Picasso. “You know… ‘bad artists copy; good artists steal.’” Maybe some ambitious VCA brat had interpreted this aphorism literally?

*

We only had one real lead to start with: the rave. But which rave? Despite the heat, pushing 40 degrees on the Labour Day weekend of the theft, it had been a big few days for parties. There was Pitch festival (described by attendees as hellish; cancelled after one attendee died), Moomba festival (parade cancelled), and Absorb(ed)III, a 37 hour party held at city nightclub Miscellania, which tends to attract zoomers dressed like cyborg Tree of Life employees as well as young-at-heart millennials. There was also Absorb(ed)III’s offshoot, Middlezorbed, an informal party that takes place in a warehouse in West Brunswick while the nightclub is closed between 1am and 7am. Had a Middlezorbed munter slipped out and done the deed between B2B donk sets?

No. Lévi was adamant. The rave had happened in West Melbourne. The pokies had been stored with a guy named Brendan, a metal-work sculptor, whose workshop is right next to the rave site. If none of our club rat sources knew of a party in that location on that weekend, we were asking the wrong crowd. We did learn, however, that on 24 March, expensive audio gear had been pinched from a rave in West Melbourne. And a few months before that, at the same location, some unknown perps had “smashed up” a party. Rave bandits were on the loose. We just had to figure out if they were also our pokies thieves.

So, on ANZAC Day, we drove to West Melbourne to meet Brendan, circling the streets first to get a sense of the area. This part of the city is desolate: a fetid little creek beneath the M2, whooshing cars, abused Neuron scooters. On one side of the main drag, Dynon Road, there is a vast lot with high stacks of shipping containers. On the other side, there is a servo with an attached Pie Face, a tattoo parlour, an environmental consulting firm, an outsized car workshop, and, further up, a mess of construction for future roads and bridges. There is also a massive cube of a building flanked by four Roman columns: a brothel. We drove up a narrow back street, and parked outside a mechanic's yard strewn with broken-down cars. A feeble alarm warbled when we got too close to the entrance.

Brendan came out to greet us. He is in his fifties or early sixties with browny-grey shaggy hair, taciturn but warm. He shares a fence with the mechanic: they’re on one side, the rave site is on the other. Brendan’s area consists of his studio, a couple of storage containers, and a large grassy patch that he has planted with gardens. On the day we visited, the yard was overgrown—he had recently hurt his back and couldn’t whipper-snipper—which only added to the sense that we were in some kind of urban grotto, like the Zone from Tarkovsy’s Stalker but set-dressed with Metro Train signs instead of Soviet era artefacts.

In October of last year, Brendan told us, Rupert Betheras called him up out of the blue. He had done a bit of metal work for Rupert, and they sometimes saw each other at art shows, but hadn’t been in touch for years. Rupert asked if he could store the pokies at Brendan’s until the ACCA show. He also wanted Brendan’s help with some welding for some of the Brio’s pieces, including the pokies, so it made sense to leave them there. “I said, ‘you can’t store any in my work area, I’m already full up in there. But there’s this area here, like this communal area, at your own risk.’ So he put ‘em all in.” They were heavy; the Brio estimates they weigh between 60-90 kg each. But Rupert moved them alone, using a trolley, into a three-walled, roof-less structure in the yard. They stood next to an old washing machine, and had a few things Rupert was intending to use in artworks resting on top of them. Each machine was covered in white-backed bubble wrap; you wouldn’t have been able to tell what they were without unwrapping them. They spent the summer there without incident.

Then, on that 38 degree Saturday, 9 March, there was a rave. Definitely? “Definitely. About a hundred people, maybe two hundred,” Brendan said. On the night, a handful of revellers cut through the fence at Greg’s (the mechanic’s), and were messing around in his yard. This was captured on a camera positioned on the side of the mechanic’s warehouse. At some point, the ravers moved from the mechanic’s onto Brendan’s property. This wasn’t caught on camera, but he knows they were there because when he went to his studio on Sunday—“I wasn’t going to go in, it was too bloody hot, but Greg rung me up”—his yard was strewn with empty cans and bottles. At that point, nothing had gone missing. He cleaned up the mess, filled up his bird bath, and went home. He came in again on Monday, watered the garden, re-filled the bird bath, and left around 5pm.

When he returned the next morning, he noticed that the bird bath was gone. He did an inventory of his stuff. All counted, he was missing a bucket of fist-sized metal wheel nut covers (the kind that go on trucks), a heavy BBQ smoker, an equally heavy pot-belly stove, and his bird bath. And, when he checked the storage spot, he realised that the pokies were also gone. Shit. He called Rupert, who reported it to the police.

As we ambled through the garden, Brendan recreated the route he thinks the thieves took. He figured they didn’t arrive or leave via the mechanic’s side of the block because the CCTV didn’t pick anything up. But further down, a thick chain securing a narrow chain-link gate had been cut. This gate leads onto a cement path, which leads to Dynon Road. They would have loaded the stolen items into a vehicle waiting just outside the gate; Brendan also noticed charcoal from the BBQ smoker dotting this route. They would then have driven down the cement path, and turned onto Dynon Road. To carry everything, they would have needed at least two people, or one strong person and a trolley, as well as a van or ute.

It seemed like a lot of effort for ravers to go to. Of course, sometimes, when raving, you open yourself up to a primordial naughtiness, a lizard-brain impulse to jump fences and smash things. But, in our experience, this energy dissipates as quickly as it comes, petering out well before one can plan and commit grand larceny. Ravers nicking a few odds and ends on the night of the rave made sense. Ravers coming back two nights later with bolt-cutters, a trolley, and a van, and selecting the heaviest items in the yard, was harder to countenance.

“Do you have any enemies?” we asked Brendan.

He didn’t answer for a while, fiddling to unlock the new, thicker chain he’d installed on the gate, then shook his head.

“I can’t explain it,” he replied. “What’s the motivation?”

We moved onto the empty lot where the rave was held. About the size of a footy oval, it's ringed by sagging temporary fencing, and looks out over the city skyline. Strewn amidst the ankle-length grass were crushed cans, empty bottles, firework canisters, plastic bags pooling with water, and shiny silver nangs. There was more of the same beneath a thin layer of dirt: rave strata.

We noticed some cobalt blue graffiti up near the roof of the mechanic’s warehouse: “CIVIK FINCH CROSA PB OGC.” Tags. As we walked over to look more closely, someone called out: “I hope you don’t think that’s art.” It was the mechanic, Greg, with a chunky labrador at his side. He told us that this graf appeared the night of the rave. If we could find out who tagged his wall…

He took us into his office to show us the CCTV footage. Greg’s cameras didn’t reach the graf, but they did get some of the ravers in his yard, in minute or so long snippets captured between 9:20 PM to 11:57 PM. In the first batch of videos, a group of boys wearing jeans, sneakers, and baggy shorts, as well as a girl in (we were pretty sure) white knitted arm warmers, assembled in the yard. They milled around aimlessly, opening car boots and jumping on bonnets, while onlookers filmed on their phones. By 11:50 PM, in one of the last pieces of footage, things had seriously escalated. It was a different crowd now. A tall, skinny guy in a baggy white tee arrived, swaying as he walked, and started kicking the tail-light of a car over and over again, with real aggression. A couple of minutes later, he handed a small, round, heavy object, possibly a wheel cap, to a girl wearing denim cut-offs. She lugged it along to a car in the row, swung it back and forth, and—we all winced—heaved into it the back windshield.

Greg shook his head. “Girls and everything!”

More shocking than that: the people in the videos looked very young. Probably high-schoolers, fifteen or sixteen years old. Some seemed a little older—taller, less scrawny—but still. No wonder we’d struggled to get info on the party. We’d been chasing the wrong age-bracket.

*

In the days after our visit to Brendan’s, we asked around again to see if we could find anyone who had been at the rave. A few people mentioned that they thought their younger brothers had gone; and we began referring to it, in our internal memos, as “the little brother rave.” We discovered we had a mutual friend with the organisers, and through them heard that they didn’t want to talk now they knew the rave might be connected to a theft. Finally, we got through to someone who’d actually been there. They’d heard about the party from a zoomer friend and arrived around 1am. The music was mostly breakcore, they said, and the vibe was “up and down.” People were young—they estimated early twenties—and wearing baggy clothes. “Some were dancing, lots more just sitting around looking at their phones. Nothing out of the ordinary, rave-wise.” They left early, around 2:30 am, witnessing neither any tagging nor an art heist. Again, we were struck by the unlikeliness of the crime: why would these nonchalant scenesters bother?

At this point, all we had to run with were the tags scrawled up on the mechanic's warehouse. Maybe, if we could find “Crosa,” “Civik,” or “Finch,” they could provide some clue about who took the pokies? Or, possibly, they'd nabbed them themselves? It's not hard to see how these artworks might appeal to a graffer’s taste. They are found objects repurposed through the application of painted symbols, and carry hefty personal lore. Also relevant: Rupert came up deep in the Melbourne graf scene, tagging up and down the train lines in the 1990s with his brothers as part of the notorious Da Mad Artists (DMA) crew. Maybe some old school graffers with a long-held grudge, or newer admirers, knew that some of Brio's works were at the shed and decided to nick them for cred?

We reached out to a few graffers to see if anyone knew anything about Crosa et al.

“Never heard of them,” Keith (not his real name) said over IG chat, after we sent him a photo of the tags in question. “Seems toy lol.”

“What does that mean?”

“Oh lol soz it seems like people who just started doing graf, not of repute,” Keith said, adding that in general, young graf kids are more into stealing small, expensive items that can be sold on eBay, not cultural artefacts whose value is essentially non-fungible outside a coterie of dedicated collectors. “I def don't see some 18yr olds wanting to take these / seeing any value in them….”

A few days later, he reported that he had spoken to his “little westside graff friend” who also thought that Crosa and Co. were amateurish: “He speculated that they might be from the eastern suburbs and have moved to Footscray. It sort of has the vibe of like Camberwell private school boy lads.”

This checked out with the CCTV footage—the kids did have a kind of private school swagger.

“Do you think it could be an inside job?” he suggested. “And graff dudes are just a good diversion?”

*

An inside job? Ah yes, one of the great heist plot motifs. We'd be lying if we said it hadn't occurred to us. The longer we spent on the case, the more unlikely it seemed that this was a crime of opportunity. We had begun to suspect that whoever took the pokies understood their origin story and their cultural value. The works were uninsured, so the idea that anyone in the Brio could profit off them going missing was a non-starter. But maybe it was someone loosely affiliated with the Brio, or, more pointedly, one of their many recent art world admirers who figured out their location, and for whatever reason, wanted the works for themselves—or wanted to make them disappear altogether. Professional admiration? Professional envy? A rival collective?

This was all baseless speculation, of course. And at TPE, we do not like to speculate, at least not when it’s baseless. So, with this in mind, we headed back down to the crime scene on a cold and blustery Monday morning to see if we could find any evidence pointing to the workings of a more sophisticated art thief. Our best hope, we thought, was to find footage of a ute peeling down Dynon Road in the middle of the night with four pokie machines bumping around in the back.

We arrived at the Pie Face at 10:30am. Joining us was Paris Lettau, an art historian and editor at Memo Review, Lévi’s brother, and most crucially for our purposes, a barrister. We could use his adversarial lens. Paris promptly bought himself a sausage roll, before asking the attendant if they had any CCTV from the night. The man recalled that there were hundreds of teens running amok in the area that weekend, but that Pie Face deletes recordings every seven days. At the tattoo parlour near Brendan’s, one of the artists said that things were often stolen from their car park. “The area is sketchy as fuck,” she sighed, adding that they have a camera inside the shop, but they close their front shutters at night time, so they wouldn't have captured any pokie theft footage.

The brothel down the road had a conspicuous camera adorned to one of its columns, but the man in the front room, which was toasty and furnished with red leather armchairs, told us that it happened to be out of order that week. It was a similar story at Connolly Environmental. A man there told us that a year ago, they found a couple of Brendan's sculptures in their driveway, presumably taken and then abandoned by burglars. “Our cameras hardly work,” he said, sounding genuinely apologetic. “They're really shitty.” Our last hope was the other mechanic, J. Pringle. Here, a guy wearing a single AirPod told us they hadn’t kept that weekend’s footage. We had come too late. So had the police—they had made similar rounds a few weeks after the rave, when any relevant footage had already been deleted.

From there, we scrambled back up to the site of the rave. Could it be that, on the night, the thieves had seen the bubble-wrapped objects, figured they must be valuable if they were swaddled like so, then, after getting their haul out of Brendan's, peeked through the protective cover to find… something hard to shift on eBay? What would you do? Keep them for the man cave? Chuck them in the Yarra? Or ditch them on the spot, saving the trip home? Wading through party detritus, we scanned the grounds. A flat-screen TV was lying face-up in the dirt. It had been there so long that plants had begun growing through the cracked screen: “Very Brio,” Paris remarked. We stomped around in the scrub edging the site and found a hiding place with a delicate little garden bed made out of white pebbles from which some wild agapanthus sprouted, but no pokies. And no CCTV in sight. This was, in some sense, hopeful—a raver’s autonomous zone liberated from the camera’s prying eye. But it was bad news for our investigation.

We caught the train back into the city and gazed out of the window, wracked with directionless suspicion. At this point, everyone and no-one was a suspect: Brendan, the last person to see the pokies; Greg, the mechanic, who could have known they were at Brendan’s; Rupert Betheras, the last member of the Brio in possession of the works; Lévi McLean, who set us down this path; Paris Lettau, of course; the kids caught on CCTV; the unknown ravers; the unknown graffers; the Pie Face mascot; that one random woman who looked at us funny at the Dynon Road traffic lights. Even TPE was a suspect now—how could we know for sure that one of us hadn’t done a dodgy deal with the Brio, a coordinated stitch-up to increase the value of the works before the ACCA show, pumping them up using devious art critic tactics? Well, because we still had absolutely no fucking clue where they were. The train scuttled around the bend in towards Southern Cross Station. Somewhere, out there, there were four paint-slathered pokie machines from the desert shivering in the achromatic city.

*

Actually, we later discovered, there are six Brio pokie machines in Melbourne. The four missing ones—unless they’ve already been shunted off interstate—as well as one purchased by Mark Chapman, a man who runs an art framing and freight (among other things) business. The other Brio poker machine was acquired by the NGV in 2022, and has since resided all on its own within institutional walls. At this late stage in the investigation, we hadn’t yet seen one of the Brio’s artworks up close.

When we asked the attendant at the NGV where we could view the work, she tapped away at her computer for a few minutes before looking up with some consternation. “Strange,” she said, “I can’t seem to find it in the database.” Strange indeed. We stumbled on through the white corridors, scanning for the Brio, until we found ourselves face to face with Picasso’s Weeping Woman.

Picasso painted this anguished, acid green face in 1937 as a “postscript” to Guernica, his grim mural depicting the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. The work was bought by the NGV in 1985 for $1.5 million, the most expensive purchase by any Australian gallery ever. Less than a year later, it was stolen in a daring heist by a group calling themselves “Australian Cultural Terrorists,” who sent a ransom note to the Arts Minister demanding (among other things) increased funding for the arts. If the demands weren’t met in seven days, they would destroy the painting. But the so-called cultural terrorists did not follow through on the threat, and the canvas was returned, undamaged, to a locker in Southern Cross (then Spencer St) Station two weeks after it went missing.

As we stared at the Weeping Woman, with her bulging eyes and black tongue, we beseeched her for answers, a sign, anything at all. And right on cue, we had a brainwave. We were in the wrong gallery. Australian art is at the Ian Potter, just over the river. Duh. We traipsed across the bridge.

On the ground floor of the gallery, in the very last section of a sequence of rooms, we rounded a corner, and finally, there it was. This pokie machine work is called Mixed Tribes (2019), and stood raised on a small white platform. The machine was made in 2003 and boasts a kitsch noughties graphic, which the Brio have preserved: a computer-generated image of a sailor rhapsodically kissing a beautiful woman, overlaid by the words “Heart of Gold.” Beneath this, on top of the old glass screen, the Brio has painted a red face, whose wide eyes peep upwards at the kiss. Stuck into the top, floating overhead like a bunch of helium balloons, are several street lights, painted with faces. The machine came up to about shoulder height, and—we could see by looking in a vent in the side—had been completely hollowed out. Not so hard to lift, perhaps.

The artwork had a serious presence. We couldn’t stop staring at it, and we felt like it returned our gaze. We could see now why someone might want to have one (or four) for themselves. Aesthetic obsession motivates some art thieves. The infamous Stéphane Breitwieser, for example, claimed that he stole two billion dollars worth of art from European galleries between 1995 and 2001 just so he could admire them in the peace and quiet of his own home. Other heists are financially motivated, of course. And then there are some, as with the case of the Weeping Woman, that are ideological. The thieves, who were never caught, used the painting to make a point about how art is funded in Victoria, and now this critique is inscribed into the work itself.

As we approached the end of our investigation, the motivation of the pokie thieves remained obscure. If there was some broader point to the heist, beyond opportunism or revenge, we couldn’t figure out what it might be. But whoever stole the pokies has already added to their lore, and become, perhaps inadvertently, collaborators with the Brio in the creation of their epic mythos. These objects now belong to the rare set of artworks that have had their meaning altered, and their value increased, by their temporary disappearance. Of course, all this is contingent on them being returned, which is really all the Brio want.

“Our appeal is to our fellow brethren,” Lévi told us. “A humanist appeal to the collective value of art. We're willing to break bread.”

When we asked Joseph if he had a message for whoever took them he told us that he wasn’t seeking revenge or retribution. “Just—please, please give them back,” he said. “We did a lot of hard work on them. We need them back."

If you have any information about the missing pokies (or any of Brendan’s items), please contact parisend.newsletter@gmail.com, or submit a tip-off here. Anonymity respected. No questions asked.