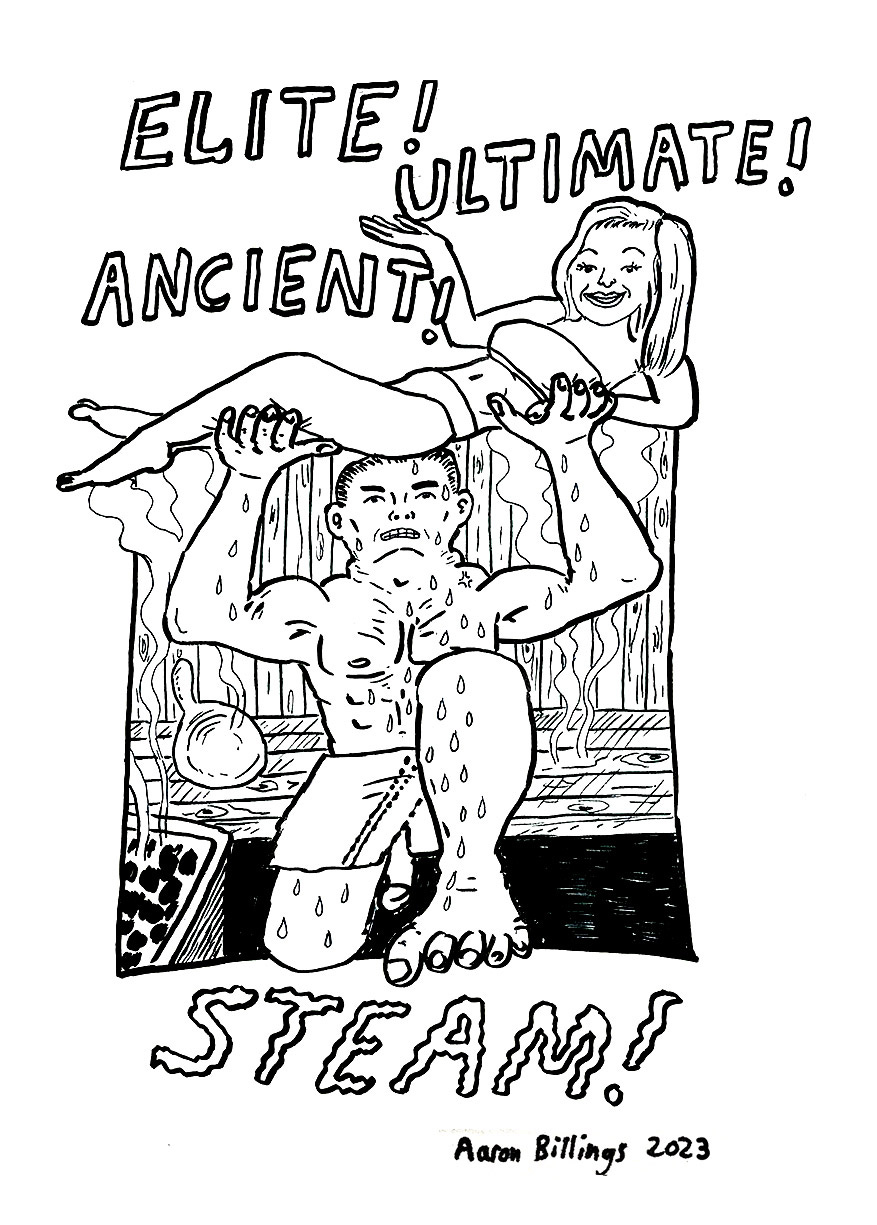

Over the summer, we’ll be re-upping three previously pay-walled classic TPE columns for you to enjoy. Up first, the origin story of Cam’s obsession with Melbourne wellness maverick, Tim Gurner, originally published April 20, 2023.

Imagine corporate Ancient Greece. That’s what it looks like inside Sense of Self, a bathhouse where “ancient wisdom and modern science collide” in a warehouse in Collingwood. When you walk through the industrial door, you leave the bitumen, tram lines, and raving lunatics on the street behind you. You can relax now. The entrance room is light-filled, high-ceilinged, white-walled, and smells good. A welcoming staff member greets you from behind a pomegranate-red stone counter. Pick up a pair of pastel plastic bathing slides and a fluffy white robe and towel. Head to the change room. Familiarise yourself with the rules before entering the bathing area: wash yourself thoroughly before entering a body of water; stay hydrated; “no pee pee in the pools”; “no hanky panky.” Suppress any feelings of aggression or irritation this language may bring up.

Enter the bathhouse. To the left, there are showers with brushed brass tapware and sans[ceuticals] lotions. To the right, a door leads to a steam-room, or “hammam,” as the Turkish call it. It’s not Orientalist if there’s terrazzo everywhere; it’s bringing global bathing traditions into dialogue. Ahead, in the main bathing area, there is a mineral pool heated to 39°C, an icy plunge tub, and a sauna. There are pot plants and feature rocks alongside decorative curtains of steel chain link. So this is what “Mediterranean brutalism” looks like. A central couch area features a snack station with dried figs, smoked almonds, and tea. You can relax among the regulars. The crowd is not quite like the one in the photos from the website—multi-gendered people of colour, diverse in age and body type, wearing soft olive, taupe, and beige underwear. It’s more WFH couples and white ladies who bathe before they lunch on anchovy toast and Chablis. Take a seat and savour an almond. Light streams through a faded scrawl of graffiti sprayed on the exterior pane of a frosted glass window. This is it. This is leisure. You feel good.

Except that, at $59 a two-hour weekday session, if your visit wasn’t being supported by the dribbles of an email newsletter slush fund, you might feel a malignant pressure to really make the most of the whole experience. Maybe you should have invested in three self-care dirty martinis instead. Luckily, today you left financial anxiety at the door, along with your phone and body negativity (though how did that girl in the sauna with the tattooed arse get so hot and skinny? Does she come here often? What’s her skincare regime?) And rumours are swirling through the inner-north about spa working conditions, with some ex-staffers disgruntled after allegedly being fired without warning. Perhaps things might not all be “no bullshit wellness,” as the Sense of Self slogan goes. (Sense of Self declined to comment without further information, which TPE was not at liberty to provide.)

Over the last two months, I've visited every bath house in Collingwood on a mission: avoid bacterial infection and gain insight into modern bathing culture.

Before the advent of private plumbing, bathhouses acted as a kind of communal, share-house bathroom for cities—places where citizens would gather to wash, flush out toxins, and gossip. To Ancient Romans, who favoured the “thermae” complex, the idea of showering solo would have seemed lonely. “Wine, women and baths ruin our bodies—but they are what make life worth living!” one Roman epitaph reads. In the mediaeval Islamic world, the hammam developed as the popular thermae equivalent. Hilal al-Sabi’, a bureaucrat for the Abbasid caliphate of 750–1258 A.D., estimated that, at one point, the city of Baghdad had 60,000 bathhouses. The settler colony we are in today has not yet reached these heights of bathhouse excellence. Depending on what counts as a bathhouse (hot springs: yes; sensory deprivation tank: no), Melbourne has about fifteen. Collingwood has four distinctive offerings.

The suburb is a typical gentrified pocket of a moderately rich global city. The streets are full of glamorous Sudanese refugees and natural wine nepo babies zooming by each other on electric scooters. New apartments rise up beside thirty-storey concrete public housing flats. Margiela consignment stores neighbour banh mi cafes and gay bars. The bathhouses—Sense of Self, Ofuroya, Wet on Wellington, and Saint Haven—are where city-dwellers with disposable income seek pleasure and leisure. Each is a sanctum that offers physical and mental respite from the harsh conditions of the outside world. And each peddles a unique escapist fantasy. It may be erotic encounters. Or authenticity. Or power. In other words, these modern bathhouses promise different kinds of fulfilment for different kinds of people. It’s no revelation to state that there are gaps between the idyll advertised by each bathhouse and the chlorinated reality. But if you soak long enough, you begin to see exactly where the cracks are. What did I learn on my quest? The most valuable things in this life are real intimacy and community, closely followed by property.

Sense of Self we know. Ofuroya, the Japanese bathhouse, is an unassuming outlier on a back street. It’s a traditional sento (a manmade bathhouse; in onsens, water comes from natural hot springs). Shoes come off at the door, and bathing spaces are nude and gender segregated. As the email booking informs me, “some rules may seem harsh to some people, but it is only there for the comfort of others and to seek your understanding of the tradition of Japanese bathhouses in Japan.” Signage that is both mildly fascist and cute appears peppered throughout the venue. One print-out shows a list of strict rules that all begin with the phrase “YOU MUST” in bold capitals. The page is illustrated with sweet cartoons of koalas and turtles scrubbing themselves, eyes closed in bliss. The warehouse roof above the heated bath is a little dingy, but the room is dark, quiet, clean, and peaceful, and it’s relatively cheap ($35). After bathing, visitors can sit on tatami mats in a room overlooking a tow truck car park and chat over edamame and tea served in mugs printed with many types of sushi.

Some Melbournians, obsessed with securing cheap flights to Tokyo and disavowing earnest scenester body positivity, are drawn to the traditional cultural superiority embedded in Ofuroya. Speaking comparatively, I can confirm that, for the soap quality at Sense of Self alone, the price difference is reasonable. In terms of the practices, Japanese bathhouses are different to those of other cultures. Are they better? Maybe. One answer is compellingly illustrated in Thermae Romae, Mari Yamazaki’s popular Japanese manga (2008–2013) turned live-action film (2012) and Netflix anime (2022). As the anime trailer neatly summarises, “a man from Ancient Rome… in a Japanese bathhouse?!” Lucius, a leading Ancient Roman thermae architect, is tasked with creating new facilities for a demanding emperor. Searching desperately for inspiration, he dives underneath the surface of a bath. Suddenly, he is sucked into a vortex. He exits in a bathhouse in modern-day Tokyo, where he encounters automated toilet lids, electric fans, flavoured milks, and wide-brimmed plastic hats that stop water getting in the patrons’ eyes. “Such a high level of civilisation! I can use this slave bathhouse,” Lucius says.

Lucius perhaps would have felt more immediately at home had he emerged at Wet on Wellington, colloquially known as “Wet.” Collingwood’s iconic sex-on-premises sauna plays host to life-sized Greco-Roman sculptures alongside a diverse range of horny people (mainly gay guys and swingers—ethically non-monogamous types prefer no hanky-panky Sense of Self). Wet is the “jewel in the crown” of sex saunas in Melbourne, says manager Shane Gardner. Downstairs, there’s a lap pool, bar, and rooms with lockers that can be secured with a key attached to a plastic wristband received on arrival. Upstairs is a rabbit-warren of darkened corridors and rooms soundtracked by moans, grunts, and slaps. Ancient Roman thermaes typically had a reception room, the “apodyterium,” which led to a hot room, the “caldarium,” a warm room, the “tepidarium,” and a cold room, the “frigidarium.” Wet opted for a “suckatorium.” Tiered entry prices reveal the ruthless hierarchies of the sexual marketplace. On swinger-friendly nights, prices are “$80 per couple (M/F), $35 per single female, $350 Per Single Male*.” The asterisk is because only five pre-booked single males are allowed in at a time. Brutal.

The first Thursday of each month, “Queer AF” night, femmes enter free. I visit with a crew. My architect boyfriend attends with some resignation, swapping out his Anne Demeulemeester blazer for board shorts and a towel. His spectacles stay on throughout the evening, fogging only slightly. One of my best friends, who visits with us, has recently developed a chronic skin condition. Their arms have just reached what Reddit calls the “red sleeve” period of the disease. Chlorine is not good for traumatised skin, so they perch poolside. Two relatively new friends/ DJs also join the journey. It’s a pretty random mix, but, honestly, the experience really brings us together. I nervously scurry around behind my more confident companions, following the sight of their G-string bikini bottomed bums bobbing through the dark corridors. People seem to be getting off. There is a liberating feeling of being profoundly uninteresting to many male patrons, as well as the thrill of potentially being an overinflated hot commodity to others. “Ooooh, she loves being here. Look at her. Look at her strutting around, loving it,” a commentator hisses from the shadows at the top of the second-floor stairs. I suddenly realise she is talking about me.

I asked my friend Vishnu, a globe-trotting bathhouse connoisseur, for some insight into the state of the local scene. He said that in Melbourne bathhouses, he felt that he could never escape the penetrating gaze of others—the feeling of being perceived. “Especially in Collingwood, which is the gay epicentre of Melbourne. That sexual gaze will always be part of the culture here,” he suggested. “I did visit Sense of Self recently, which was a bit gaze-y as well, but that just felt like regular Collingwood people checking each other out.” By comparison, he said, laughing, the last time he visited a bathhouse in Japan with his boyfriend, “this group of four eighteen-year-old boys, who were fit as fuck, came out completely naked and sat with us just chatting, like, ‘Where are you from?’ It was so sweet.’” Anglo-Australian culture has a deeply taboo relationship with nakedness that is hard to deprogram. We can’t help but watch ourselves being looked at.

As such, gender and sexuality have, predictably, been a source of tension in the bathhouses. Sense of Self is welcoming to all with Hope St Radio pocket money, but ceased nude nights, citing “an increasing number of inappropriate enquiries” that meant there was “the possibility of people coming to the space with untoward intention.” That’s what Wet is for! But Wet management have had their own troubles steering a legacy cis-het gay male space into an increasingly queer world. A 2021 customer survey about trans visitors incited transphobia and excoriating criticism. The venue apologised and has now doubled down on gender-inclusive policies. And a few years ago, Ofuroya was the subject of ire for their strictly binary business (although protests were tempered by the widely acknowledged bad look of forcibly imposing Western frameworks on non-Western cultures). Now, having seemingly registered the feedback, rules sent by Ofuroya before a visit request that “if you are transgender gentleman/lady, please contact us and discuss options.” This statement is followed by an emoji of a smiling bug, which is difficult to know how to interpret…

Sense of Self is clearly winning the gender battle here. It’s a tough gig, but these three Collingwood bathhouses are all trying to create some sort of welcoming hodge-podge of Greco-Roman-Japanese-Turkish-Anglo-Aussie bathing culture in a place that is, for the most part, uneasy with unknown bodies in close proximity. Sure, Sense of Self is kind of annoying—as is any other Pinterest-pilled millennial’s self-care hustle. In some dark corners, Ofuroya looks as outdated as its early-2000s website. Wet has tragically trashy marketing and, on the night we visited, a few persistent leches. But whether it be from hours of no-phone-time or the healing waters, it’s undeniable: I left each bathhouse relaxed and ready to re-enter the Naarm grindset. After Sense of Self, I felt dewy and affluent. Post-Ofuroya I felt centred and calm. Wet made me a little panicked (the following day was punctuated by pornographic flashbacks), but I ultimately felt excited—alive to the possibilities of human sexuality. These places don’t live up to the dizzying heights of their respective fantasies, but they basically deliver on their promises. This seemingly lacklustre achievement should not be undervalued, because the more I sweated my reportage out, the more I began to realise: there is a deranged outlier in the Collingwood bathhouse scene.

*

On Wellington St, a few blocks south from Wet, ten brand-new multi-storey apartment blocks materialised in 2022. The apartments were built by the “Gurner™ Group,” a billion-dollar property development conglomerate headed by Tim Gurner. Gurner is like a New Age Australian Trump, and looks like Beavis and Butthead in a slim-fit suit. He is a small, white man of 40 who wears his sandy hair in a waxy slickback. This emphasises his beady blue eyes. He has performative inclinations—apparently, he once released twenty white doves at a deal launch. He also has remarkably well-preserved skin. This is not a coincidence. The man is a spa visionary.

In 2016, Gurner was a young upstart developer, building his portfolio, selling millions of dollars of apartments, being a boss. Then, the market shifted, building costs rose, and Gurner ran into trouble. The apartments he was building in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley were going to cost $50 million more than he planned. Putting it politely, Gurner was fucked. He was facing calls from furious investors and staring down the barrel of failure. What would you do in this situation? Gurner called a guru. Nam Baldwin is an “elite performance coach” who can hold his breath for over seven minutes. “I’m entering a war,” Gurner said to Baldwin. “In six months, I need to be insanely physically fit. I need to be insanely strong mentally. I need to be able to endure a lot of stress, a lot of pain… I want to be able to work twenty-four hours a day and not break.”

Gurner began taking serotonin, dopamine, Gamma aminobutyric acid supplements, protein powder, creatine, collagen, and something called “Athletic Greens.” He continued mindfulness, breathwork, ice baths, and red-light therapy. Alongside Baldwin, Gurner hired an executive coach, a strength and conditioning coach, a yoga teacher, and a Pilates instructor. The formula worked. He built the Brisbane apartments and emerged stronger than ever before. Does this sound appealing to you? Because you can have it. Gurner is now selling his wellness regime at an exclusive location in Collingwood. “I’ve got this unbelievable team of the best people in the world,” he said late last year, with more than a hint of Kendall Roy-ness. “Why can’t I bring them all into a club and offer the person on the street an experience that’s cost me millions?”

Massive posters for “Saint Haven,” Gurner’s new “private wellness club,” line the street-level facade of the new Wellington St apartments. In one, a ripped Black guy stares soulfully into the camera while lifting a skinny white girl up on his back, their arms enmeshed in some sort of gym-junkie mating ritual. Renders show what the interiors of Saint Haven will supposedly look like. There is a dome-shaped meditation room with a feature Bonsai tree. Steamy, turquoise blue bath water refracts light on the arched rooftop of a sandstone pool room lit by hundreds of candles. Honestly, it looks really good. Walking past, I notice a QR code. I take out my phone, follow the link and, in a trance, enter my details so I can be added to the exclusive Saint Haven waitlist. Shortly afterwards, I receive a text from a “Health Coach,” who offers a few “VIP” time slot options to visit the “Preview Suite” and discuss my potential membership. “P.S.”, the message ends, “We look forward to helping you live your ultimate life.” I nominate a time.

On the day, a beautiful young woman in a crisp white shirt meets me at the entrance. We get in the lift and she presses the button for the penthouse suite—the club is still under construction. I smile nervously. Suddenly, I take a look at myself through her eyes: blotchy, casualised-academic skin, unironed pants, low net worth. Inside the penthouse suite, everything is neutral and sparkling clean—grey marble surfaces and taupe couches with white fur throws. A bottle of pure Australian mineral water materialises in my hand. I take a sip. It’s delicious. My Preview Coach turns on a massive TV and starts the Saint Haven slideshow.

There is a gym, a co-working space, and an organic wholefoods restaurant with not a seed oil in sight. A cycling room features state-of-the-art bikes that look towards a gigantic video of a scenic road. Everything looks amazing and nothing is as it seems. A water bubbler is actually a “Fountain of Youth.” The pools are actually “Ancient Baths.” I ask if I can see how the site downstairs is progressing. According to media coverage, the club was initially meant to open in March. This shifted to April. My Coach says no, but that I can be reassured knowing that the Gurner™ Group has a reputation for bringing renders to life.

She redirects my attention to the membership options. A platinum membership costs $145 a week and includes access to Lymphatic Compression, Cryotherapy, and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (apparently one hour of this is equivalent to six hours of sleep). A “Black” membership is $299 and means more access to Ancient Bath time. An “Ultimate” membership is the $499 highest tier. I am quickly learning that, within the Gurner™ universe, “ultimate” is the most powerful word. This tier includes two intravenous vitamin infusions per month. Ultimate success is pretty much guaranteed.

A $700 sign up fee gets you an “Oura” ring, which monitors minute shifts in your breathing and sleep patterns and sends the data to a linked app. Gurner started wearing his Oura ring during the Brisbane existential property crisis. According to a profile in Forbes, Baldwin, the breathwork guru, would be alerted any time “Gurner wasn’t in a ‘good place’” and would “talk him through what his mind and body were experiencing.” My Preview Coach shows me her Oura ring, a simple, gold band. She asks if I’d like to be fitted out for mine. I panic. Truthfully, right now I don’t have enough cash for even an Oura, let alone a membership.

“Thank you! I’ll think about it,” I say.

She walks me to the lift. I head down and re-enter the street. Underneath one of the billboards, I notice that, inexplicably, a small, perfectly-lifelike metal eel has been affixed to one of Gurner’s tiles.

What a stupid fucking crackpot bullshit zone for late-capitalist woo woo productivity freaks, I think, striding away. There is no way that stuff works. There is no way those renders will be what it really looks like. But that night, my subconscious betrays me: I dream of being a Gurner girl. We’re on the rooftop of the apartments. I’m radiating energy from an hour of Hyberbaric Oxygen Therapy. His wife is trying to get him away from me, to drag him back to the penthouse suite and their two young children. “I just have a few questions for you…” I say alluringly from a pool lounge. Gurner draws closer. His skin has an uncanny, golden, glistening texture. It’s as if Edward Cullen got into the Aussie property market. I wake with a start.

In the cold light of the autumn morning, I grew sceptical once more. When it is unveiled, will Saint Haven actually deliver on the hype? Probably not. This is not just baseless speculation. Compare the advertising faff of the Wellington St apartments to their reality. The apartments, called “Victoria & Vine,” are meant to bring together New York’s Meatpacking District with Soho House sophistication and East Melbourne cool, or something… A bizarre promotional “film” shows the imagined ideal resident: a metrosexual in Ray-Bans, scarf, and trench coat who drives a vintage orange Porsche and listens to smooth jazz (a hipster Gurner proxy?). Gurner’s website has no images of the finished project—just endless renders accompanied by asinine copy.

In real life, the charming neighbourhood bar rendered on the ground floor, “The Coin in the Fountain Brewing,” has not materialised. Instead, there is just a daggy sign advertising a financial services firm called, I kid you not, “Paul Money.” The website promised a “library.” This seems to have turned out to be decorative shelves filled with hardcover books in the apartment foyers. The rooftop pool area, rendered with an abundance of luscious greenery and a life-sized golden bull sculpture à la Wall St, looks terrible in aerial footage published in a video by one of the Gurner™ Group’s partners, Pacific East Coast. The bull has a faded patina and looks forlorn. There are a few shrubs.

Pacific East Coast is an investment property “syndicate.” The group advises their clients on the acquisition, management, and sale of investment properties like Victoria & Vine. This partly explains why, to the intended viewers of their videos, it doesn’t particularly matter if the renders don’t match reality. The glowing JPEGs are there to facilitate the feel-good exchange of assets, activity that occurs above the heads of the property-less tenant pool; they’re basically NFTs. “Feedback from our clients is that the rents have just outperformed,” says Pacific East Coast Managing Director Brent Severino. Gurner nods emphatically. “The rents here are blowing my mind,” he says. Excellent news for the people on the street.

Over the course of writing this column, I tried to penetrate the walls of Gurnerland and speak to someone from the inner sanctum. I called the Gurner office and emailed the Gurner group to no avail. I texted my Health Coach to see if he or Tim Gurner would be open to an interview about the project. The response: a polite no. They were focussing on getting the club open. But I wanted a real counterpoint to all the promotional material I’d been imbibing, from someone with firsthand Gurner experience. I called Stephen Jolly. Jolly has been a prominent socialist on the Yarra City Council for nearly twenty years—he is at the decision-making table when Council discusses the approval of Gurner’s development permits. He also works in the construction industry. As a militant left-wing Irishman who grew up in social housing, I thought he’d be fiercely critical of Gurner’s activities. His response was more pragmatic.

“Tim Gurner is exactly what he looks like,” Jolly says. “He is a developer worth $600 million [actually $788 million, according to the Australian Financial Review] and he is trying to maximise profit for his company. That doesn't mean that he's evil incarnate. He is a developer who's going to do what developers do. He’s not pretending. In that sense, from my perspective, you can deal with somebody like that.”

Jolly is trying to get the Yarra Council to enact zoning policies that incentivise—ideally, force—developers to include a percentage of affordable residences in new buildings. According to him, Yarra is ready for radical action and Gurner is amenable to coming along for the ride. He doesn't want to speak poorly of someone he thinks can be leveraged for genuine housing redistribution. I suggest that the Gurner™ Group might not always deliver on their renders, and that this might be a problem. Shockingly, Jolly doesn’t seem to care that the Gooped-up ruling class might be disappointed with their co-working spa. He thinks Saint Haven will probably be good. He knows people who work on Gurner sites, and reckons that the developer’s obsessive tendencies mean that the quality of his buildings is high. “He's a bit mental,” Jolly says. “Even though he's worth, like, over half a billion dollars, he will turn up at five o'clock in the afternoon, get on his knees, and check the paintwork.” The Gurner buildings look pretty average to me, but what do I know about construction? Still, I know bathhouses. And I know armchair psychoanalysis even better.

At some point during my bathhouse research, I listened to a podcast interview with Gardner, the gruff manager of Wet on Wellington. Gardner recalls what it was like being gay in Australia in the ‘80s and ‘90s. “Society expected a white picket fence and two kids,” Gardner says. He was married with children before coming out at 40. “I did that. I loved that. But you know… to live a lie? It didn’t work for me.” Gardner’s observation gave me pause. It used to be that you had a real white picket fence and a fake marriage. Things have changed. Now you can have a real marriage—gay, straight, poly, whatever—and a perfectly rendered faux-Soho loft that you can’t afford to live in.

Everyone has fantasies; everyone pursues them; everyone deals with the experience of deflation that accompanies the period when the object of desire loses its aura upon attainment. That’s life, man. At times, I feel weirdly sorry for Gurner. Most of us just want, like, new AirPods and to be made love to in a Maroske Peech geotard. We feel temporary despondence when wish fulfilment doesn't lead to perfect emotional wellbeing. But Tim Gurner enacts this process of desire on a pathologically grandiose scale. The world-building scenarios he creates under the guise of apartments and wellness centres can only produce disappointment when the ideal confronts the real. Even his name betrays him: “gurning” is the grinding, clenched-jaw side-effect of MDMA, the overflow of desperate energy from a drug that produces feelings of intense euphoria and connection, closely followed by cold hollowness. Construction on Gurner and his wife Aimee’s personal apartment in St Kilda—a mind-numbingly expensive “wellness residence” with a custom infrared sauna—just finished. It was the Gurners’ ideal home. Tellingly, they immediately put the property on the market.

The fee-paying members of Saint Haven, whoever they may be, will have to live inside Gurnerworld; they will want their physical flesh immersed in some form of real, steamy Ancient Bath water. Pulling this enterprise off is a test of Gurner praxis. In April, I walk past the club again. The opening is meant to be imminent. On all my other visits, the entrance has been covered by a trompe l’oeil sticker: a pair of burnished golden doors emblazoned with the Gurner™ logo and a sign that reads “PRIVATE CLUB.” Today, the doors have swung open. A messy construction site lies inside. There are buckets of Gyprock on the floor, cords dangling out of the walls, and fluorescent orange safety poles everywhere. A tradie returns my stare. As I continue to snoop around, a schlubby guy emerges from one of the apartment foyers to wait on the street for a delivery. A real person! What does he reckon? Will I be able to bathe in the rejuvenating waters of the mineral pool on the final step of my bathhouse journey? Can I meditate in that stone cave chamber any time soon? He gives me a sardonic look. “Don’t hold your breath.”