The year is 1565. You’re wearing a mask on the top half of your face that does not impede the consumption of a pork sausage. It’s spring, a cool twilight, just before Lent. You’re parading through dirt streets, part of a band of friends making merry. Your neighbour holds a pig bladder and is wacking it on the heads of villagers as he passes by. The wind carries the scent of frying batter and roasting meats, and the sound of bawdy songs, animal cries, shrieks of laughter. You see the priest sitting backwards on a cantering donkey, led by children. You’re a man but you’re in a dress—you’re all men, you’re all in dresses—and now you’re running away from your wives, who are speedy in pants and carrying sticks. Later there will be more ale, more food, and liaisons in dark houses. The next day you will have a hangover and nothing in the cupboard.

The year is 2023. You’re standing in a field of yellow grass eating a fried sausage on a stick. You’re staring up at a huge, swinging metal arm with a fist of cages on the end, imprisoned in which are screaming teens. Surrounding you are thousands upon thousands of people, most of them dressed in shorts and T-shirts, caps (on the men) and straw sun hats (on the women). An unstoppable tide of strollers rolls over the plains, weighed down by showbags, water bottles, nappy bags, half-empty boxes of food, and babbling infants. It’s late September and the sun is unrelenting. Armed police officers survey the scene. The mechanical arm swoops towards Earth, then up again, like a comet on a string yanked back towards the heavens by a merciful God. You consider buying a $15 beer from the fenced-in section where you’re allowed to consume alcohol. You have work the next day. You forgo the drink.

*

I moved to Melbourne almost six years ago but, until a few weeks ago, I had never been to the Royal Melbourne Show. Sorry—I mean, Melbourne Royal Show. Last year, the Show’s parent organisation, the Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria, became simply Melbourne Royal® and renamed the show to match. The CEO of Melbourne Royal claimed that the name change “provides an opportunity to grow” and that it’s “a point of difference” from all the other Royal Melbourne organisations out there. On Reddit—where I go to glean practical information about my visit—there is a vicious debate raging, or there was, a year or so ago when the rebrand was unveiled. “What a woke lot of rubbish, leave the name alone,” wrote one user. “It's been the royal Melbourne show since I came here as a migrant in 1965. More green lefty rubbish.” Others suggest that it reflects a broader trend—that the Show is moving further away from its humble agricultural roots, and leaving itself room to pivot fully into a money-grubbing amusement park. A petition from 2017, which has upwards of 3000 signatories, calls on the Melbourne Show to stop the debased entertainment and return to tradition. “HORSES and cattle are no longer allowed in the main arena,” the petitioner writes. “GRAND parades are no longer held. FAMILIES can only see competition horses or cattle in their stalls if accompanied by a security guard.”

Why did I go to the Show? I don’t like rides, I don’t have kids to entertain over the school holidays, and although I do like seeing chunky cows and gorgeous chickens, neither have that strong of a pull. I blame Mikhail Bakhtin, theorist of the carnival. I’d read his book on Rabelais and carnival during lockdown, and it had lodged, festering, deep in my subconscious ever since. Carnival was a ritual period of debauchery common to Western Christian countries, especially Southern European ones, during the Middle Ages and early modernity. The word “carnival” comes from Latin. Carne means flesh, and levare means to lift or to lighten; roughly, this translates to “putting away meat.” Carnival fell just before Lent—typically between January and mid-February—during which observers gave up particular foods or habits. Before this period of abstinence and fasting, revellers would consume goods that wouldn’t last over the next 40 days, especially meat and dairy. Sausages were a big thing, as were pancakes.

But carnival wasn’t just an excuse for a dutiful proto-fridge clean. Carne is also carnal. It instituted a topsy-turvy world in which hierarchies were upended and venal appetites were celebrated. Actors often wore masks, and had licence to enter private dwellings as part of their plays. People threw eggs, flour, and apples at each other. They drank a lot and got violent, sometimes harming each other and sometimes doing bad things to animals. In France, the second-most common time for babies to be conceived was during carnival (the first was spring). Bakhtin wrote that carnival made the world into “one great communal performance… opposed to that one-sided and gloomy official seriousness which is dogmatic and hostile to evolution and change, which seeks to absolutise a given condition of existence or a given social order.” I imagined that the Melbourne Royal Show would contain a carnival impulse—a feral spirit of feasting, of royalty dethroned, of looting and singing and Bertie Beetles for all.

I gather three carnival-appropriate companions for the event: Kat, Melody, and Moyshie. Melody grew up going to the Lismore Show. She remembers it as “a kid’s version of totally writing yourself off.” I asked Melody to come with me in order to apply her keen scholarly mind and her poetic sensibility to the spectacle. She is researching what she calls sites of “colonial kitsch,” of which the show, obviously, is a prime example. Kat spent their teen years at the Cairns Show and also competed in two rodeos at the Tennant Creek Show. Moyshie’s main childhood show stomping ground was here in Melbourne, which he describes as “manic, clowny, fun, dark…It felt chaotic. And I felt possessed.” As for me, I’d attended the Maryborough Show up until age sixteen, where I’d even won several prizes for my artistic juvenilia (mostly pencil sketches of celebs, and one touching portrait of a frog family). We all remembered the teenage frisson of the show at night: sloppy make-outs, vodka from plastic water bottles, drink driving the dodgems. Hoping to recapture this mood, we purchase “After Dark” tickets. These cost just $29 for adults, compared to a daytime price of $47.50. Kat and I arrive at the showgrounds in Ascot Vale just on twilight.

It’s underwhelming at first. Closest to us are the milk and cattle sheds, and these are closing up for the evening. About 100 metres in, across some scabby grass, there is a section of looping, bitumen roads. Dotted along the edges of these roads are sideshow alleys, food trucks, tents selling random goods like perfumes and hot tradie calendars, ice cream and fairy floss vendors, a Haunted House, a Haunted House escape room, and, of course, the rides: a ferris wheel, the aforementioned swinging metal arm, roller coasters, a UFO-themed anti-gravity spinner, a gigantic slide, a hideous machine where passengers are placed in spinning cages attached to the tips of rotating stalks, and a kind of turbo merry-go-round in the sky. Each ride blares its own personal EDM, and many of them are painted with uncanny valley murals of C-list celebrities—a warped Delta Goodrem leers over a rock star themed ride. In the ride section of the grounds, every nook and cranny is absolutely packed with show-goers. Many of them are wearing pink, purple, or black cowboy hats, which are available from several of the stalls. We step into the crowd to take a closer look. Now we’re overwhelmed. Kat and I are engulfed and spat out a few hundred metres later into a quieter picnic area next to a petting zoo, where we finally manage to link up with Melody.

We regroup around a bench and chairs that have been made to look like timber, but which are actually constructed from hollow plastic; the unit tips up a little when I sit down on one end. Melody—bleached curls unruffled—explains that there are levels of participation available to us. You can, in theory, just look around and marinate in the ambience, or you can get involved. Getting involved means purchasing things. We need to get cowboy hats, she explains, and then we need to go on the gigantic slide. After that, we’ll escalate our involvement, perhaps with a scarier ride. I get a black hat, Melody gets pink, and Kat remains un-hatted. We cling to the brims as we launch down the wavy, rainbow plastic of the slide. By the time we reach the bottom, it’s worked—we’re woo-ing and cracking jokes, and we melt into the crowd seeking further thrills.

Meanwhile, Moyshie has been stuck on a peak-hour train for the last hour. He has had to disembark at a stop in the city and race over on a Lime scooter. We find him in the entertainment arena, where DJ Kitty Kat is amping up the crowd. DJ Kitty Kat—who is also an award-winning fitness model, with the kind of rock-hard arms most of us can only dream of—is owning the space. At the front, there are teens and mums jumping up and down to unidentifiable techno remixes, while the dads hang back with bags and prams. Further back still, hordes of children are raving on the grass. A tiny girl in a fairy skirt is flailing her arms and legs to the beat, and staring ahead with the glazed eyes of a true munter. As I watch, a parent intervenes, breaking her off from the dance floor. She starts crying as she’s dragged away. Moyshie is pumping his fists, euphoric. We decide to go get showbags.

The showbag pavilion is a hangar-like space with vendors lining the walls. It’s mercifully empty, though this is also because many of the best showbags have already sold out. The bag I want, the UCLA showbag—branded sweater, gym bag, water bottle—is sold out. The Swords & Sorcery showbag is sold out. The Nerds showbag is sold out. I settle on the Rural Aid showbag, which is on special, from $18 down to $12, and apparently contains goods up to the value of $150. The attendant hands it over and I realise immediately that I’ve made a huge mistake. It comes in a hessian shopping bag and includes, among other things, a bottle of chlorophyll, a mini Grants toothpaste, a 15g packet of craisins, a bottle of green chilli Sriracha, an aerosol can of foaming deodoriser carpet spray, a jumbo packet of spiral pasta, a 1L carton of low sugar Golden Circle Berry Burst Refresher, and a 1KG bag of plain flour. It probably weighs 4 or 5 kilos. I ask if I can return it. The attendant points to a No Refunds sign. “There are lockers outside,” she says. I go to the lockers. They cost $14 each. I forge ahead with Rural Aid by my side.

For a while, I wander off alone among the sideshows, lugging my sack. Games have really come a long way. Some of them are now entirely digital, displayed on massive screens. To play them, you don’t shoot a gun, or cast a fishing line. You do some kind of magical hand gestures and the screens light up and make sounds in response. The sideshow spruikers have head-set mics and are roving in front of their games, vacant and aggressively present at the same time—they speak in an unceasing patter while also scrolling their phones. One worker is standing on a raised platform in front of a big screen, wearing dark wraparound glasses and low-cut jeans, looking like she’s stepped in directly from Misc.

I come across a young woman working alone, guarding a wall of fluffy toys. She is 21 years old and has just moved here from the UK. She works at this stall 12 hours a day, for $20 an hour. She tells me that all the other employees are also recent migrants, and that the woman who owns this one owns 18 other stalls. When she had her job interview, the boss said that if she didn’t agree to work every single day of the Show she wouldn’t get hired. She is not into it; she knows she’s being exploited. At another stall—a throwing-ball-in-bucket type game—I speak to a manager. She was born into the business, and now owns three stalls. Her family and her staff travel all around Australia together, towing their attractions (which fold up neatly into big white trailers) from show to show. If you go on the road with them, you don’t get paid extra for travel or for the time away from home but you do get free accommodation. I catch sight of the interior of the trailer she lives out of while on the road. The wall is tacked with family photos, a wooden cross, and a framed Rumi quote that reads: “Seek the path that demands your whole being.”

I rejoin the others, who are now waiting in the queue for the KIIS 101.1 FM Haunted House. When we get to the front, we put our bags, including, thankfully, Rural Aid, in a large box. I ask a girl in white face paint if you have to be an actor to work here. “Um, no, literally anyone can do it,” she replies, ushering us into the dark interior. We clutch each other as we inch through the first few rooms. The walls are lined with flapping doors, and the path twists and turns. Clearly, something is going to jump out at us, and when it does—a chainsaw murderer covered in blood—we all scream in unison. The tween girls in front are looking back at us for support as they enter new rooms. Somewhere towards the middle of the house, I hear them gasp. My group pushes me to the front. There is a sheet of laser light cutting the room in half. If we stood up, our bodies would be bisected by it, but we don’t stand up because it doesn’t feel right. Instead, we all crouch down and shuffle along inside the light. It feels like we’re underwater. There are things on the surface dipping in. A dead face lurches down at us, and we scream. In the second last room, a half-hearted demon opens a flap and lazily waves an arm. The flap gets caught a little before it opens, so we have plenty of notice. We scream anyway.

*

The show, at least in Australia, has a very different history to carnival. Its origin is specifically agricultural and, as befits the colony, specifically British. Over in the Empire, local agricultural societies had been forming and gathering since the mid-1700s. These were assemblies of land owners, gentry, and farmers, who met to exchange knowledge and farming techniques. Farmers displayed their animals, amateurs showed off their produce, and scientists gave lectures on soil health. Depending on who was involved, these gatherings were either valuable sources of information led by those working the land, or a way for the nobility to monitor their food-producing underlings; agricultural societies would award premiums for particular farming innovations, but also sometimes for more abstract ideals like “good conduct.”

The Royal Agricultural Society of England formed in 1837 as an overarching national organisation. It held its national Show for a week over summer, an event which attracted the usual mix of scientists, farmers, and land-holders, but also a wider general public and the press. (A paper called The Agricultural Gazette boasted of its “six gentlemen” journalists, “engaged in the daily trudge… in the endeavour to describe the show to readers.” The Paris End regrets that it could send only one ungentlemanly journalist this year.) The Show did not have its own grounds and instead roved between towns, which would compete to be selected as the host. The winning town would seize the opportunity to make its mark on the nation. A Show would usually include not just pastoral business but balls, concerts, and lavish feasts served to the gentry and noblemen. Outside of the pavilions, enterprising locals would set up refreshment booths and circuses would pitch their tents for the week. These were controversial, and often accused of detracting attention from the true purpose of the Show (to look at sheep). By the 1860s, though, national shows brought some of these auxiliary entertainments into the grounds and used them to raise funds, for instance, by charging fees for stall-holders. After attending the Manchester Show in 1869, one columnist wrote that there were “exhibitions within exhibitions, [which] overlaid the show itself with absurdities, only to get more crowns, half-crowns and shillings out of the unfortunate public.” One wonders what he’d make of the topless tradie calendars and the giant off-brand Pikachu stuffies.

Like those in England, Australia’s early shows were focused on advancing agricultural science. Commercial manufacturers showed off the latest equipment for sale. Government agencies spruiked their policies. But they were also exercises in nation building—a way of bringing town and country together, of displaying settler ingenuity and mastery over the land. In the early days of the colony, the first public market for livestock was held in Parramatta, and the first agricultural show took place there in 1823. Whenever a new town was made official by the colonial government, it would, generally, start its own agricultural society and put aside some land for a showground. The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria formed in 1840. In the 1880s, approximately 70 new agricultural societies were established, and by Federation, there were around 1000 shows held regularly across Australia. The only times the yearly show in Melbourne hasn’t been held since its inception in 1848 (COVID lockdowns aside) was during the Boer War, World War I, and World War II, when the grounds were requisitioned for military purposes.

The Australian shows quickly became hybrid events: part entertainment, part edification. At first, showmen, or “showies,” who travelled around with the festivals, were only allowed to peddle their wares and attractions at night, but by the 1910s, they had daytime privileges too. In 1911, the Victorian Agricultural Society decided to give unoccupied space in the grounds to “side-shows,” whose holders would pay a fee to the Society and, hopefully, bring in more punters. This decision was based on the show in Sydney, which had become a popular and lucrative affair full of carnivalesque curiosities. Online at the National Sound and Film Archives, you can watch a short reel filmed at the 1933 iteration of the Sydney Show. It shows a man wrapped in snakes, a dog in a ruff climbing a ladder, a few rickety-looking rides, and a sign inviting patrons to come and observe “Elsia,” whose “right side [is] like that of a beautiful woman, the left like that of a powerful man.”

I ask Melody to conduct an analysis of the show through the idea of “colonial kitsch.” The show, says Melody, feels “obvious as a form of kitsch, as this intense accumulation of really garish commodities.” But colonial kitsch is specifically about “the manic reproduction” of settler-colonial myths of nativism. “Some of this happens through particular figures, including the battler, the pioneer, the melancholic, and the larrikin—Australiana staples that are often deployed in nationalist myth-making. All of these archetypes are in circulation at the show.” For instance, the event is implicitly marketed towards “the battler,” who is taking a deserved break to enjoy a good time out with his family. “And then there’s the agricultural component,” she continues, “which is selling a different kind of product—this specific idea of what Australia is. This intensely colonial idea gets hidden or lost behind the innocence of the show as a spectacle of fun.” The obfuscation is literal, too: nowhere in the Melbourne Showgrounds or at any of the events are there any Acknowledgements of Country.

In one tab, I watch the reel of the Sydney carny action. In another, I look at a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder called The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559), which depicts an epic battle between the forces of excess and temperance. The predominant colours are earthy browns and sickly yellows, with splashes of red and sky blue. Towards the bottom of the frame, a personification of Carnival—a pot-bellied man with an obscene codpiece, riding a barrel and wearing a pie as a hat—thrusts a rotisserie of meats. Opposite him is Lent, who is depicted as a thin, elderly woman. She sits on a spindly chair, holding a spatula laid with fishes. The two are jousting, each borne forward by their attendants. Carnival’s troupe are wearing pots on their heads and playing music. Lent’s crew are small, sombre children carrying pretzels and flat loaves of bread. In the background on Carnival’s side, there’s an inn, whose upper floor is crowded with spectators; one of them vomits from the window. On Lent’s side, pious citizens are giving alms to beggars.

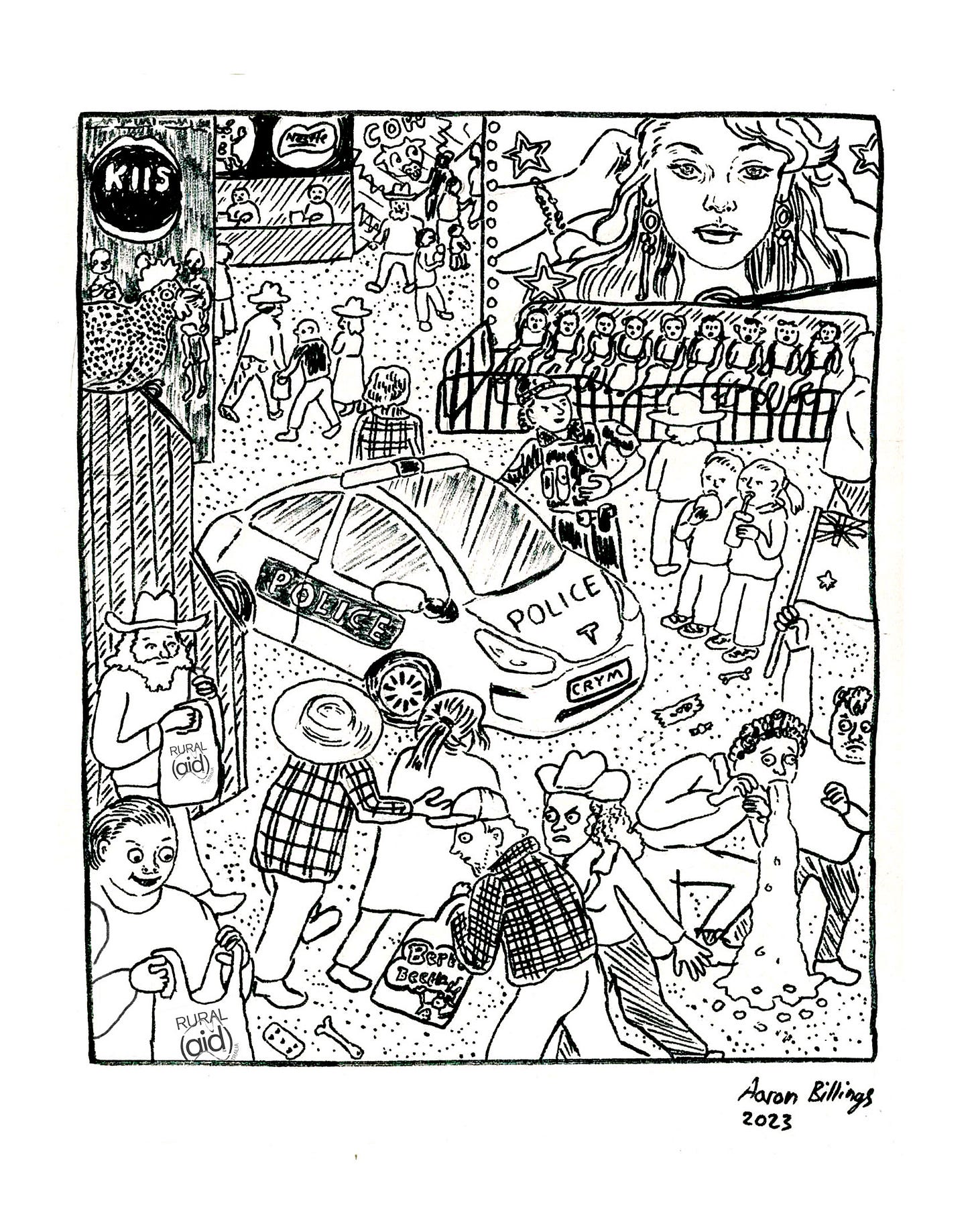

In Melbourne, 2023, the kids and teens are at the frontline of a similar battle. On the one side: a motocross show, with three riders flying through the air on their bikes. Teen girls are screaming and, afterwards, clamouring for autographs. The kids are on their parents’ shoulders, rapt and squealing. The grounds are littered with trash and there is a pool of vomit next to a bin. Beside me, Moyshie, belly poking out from under his ridden-up tee, is eating a massive dagwood dog dipped in sauce. On the other side: security guards, cops, parents, and Rural Aid, which I’ve plonked on the ground to give my shoulder a break, and which—I see now—is a hessian sack full of non-perishable items of the kind that could see one through Lent.

*

I really, really do not want to go back to the Show. And yet, the next day, after I wake up, I shower and dress, drink a coffee, and get on a tram back towards Ascot Vale. At night at the show, you can put yourself within spitting distance of the fundamental chaos that undergirds the universe. In the daytime, all the forces whose sole purpose is to quash and corral this chaos are in ascendance. I have to see both sides. If you want to understand why a show in current-day Australia is not like a carnival in early modern Europe, go to the Melbourne Royal Show during the daytime on a public holiday.

I arrive at the grounds around 11am. Right away, I can sense it—a bugle on the wind, a baked-in national pride (even the grass is khaki coloured). It feels bad, man: patriotic in the way of an ANZAC day ceremony, enervating like a church service as a child. You feel it most acutely when you’re schlepping between pavilions over the open plains of grass. One of my aunties used to keep cows—not a crazy amount, but there were a few. I remember going to her place as a kid for Christmas. As I trudge through the entrance and make my way into the grounds, I’m followed by a distant mooing. It feels like I’ve never left Queensland. Like I’ll never get out of the regions and make it to the city. I’m a child and my parents are napping in the recliners after lunch while I run around in the dry grass outside, until I step into a fresh, steaming cow pat, and start crying, and my siblings are laughing at me and I can smell smoke coming from back-burning on the neighbour’s property—

I come to holding a dagwood dog and a Bertie Beetle showbag. I haven’t tasted a DD or a BB for at least fifteen years, and both are just as good as I remember. I feel revived by the protein and sugar. I accept a free sample of Bondi Sands SPF 50+ sunscreen and apply it to my face and neck. I put my cowboy back hat on. Pushing through a blonde family of four, I find a shady spot, and unfold my map. For the next hour, I stroll the grounds, peeking into the Pavilions that were closed last night. In the PURA Pavilion, which is marked by a giant inflatable PURA milk bottle (literally Big Milk), two forbearing cows are being milked by lines of children, one after the other. In the Livestock Pavilion, there are cows the size of a Hyundai Getz, but there are no pigs; pigs have been deemed a biosecurity risk and banned from the Show—an anti-carnival gesture if there ever was one. Of all the chicken breeds on display, the Bantams are the most extravagant: puffballs with hard bits poking out. Their feet look like dried starfish with fluff glued on top of them, and on their foreheads they have ruched folds of skin that look like an external brain. In the 9 News Lifestyle & Local Heroes Pavilion, giggling primary schoolers are getting in and out of a display Tesla cop car, and a lady cop at a recruitment station is talking to a dweeby teenage boy. The farmers and their families are all wearing genuine cowboy hats, blue jeans, and button-downs. In our frivolous cardboard hats, we look like we’re paying homage to the real deal, the way Harry Styles fans wear feather boas to his concerts. A mother tells her crying toddler: “Well, you’re not getting a showbag, how about that?”

*

By the time I make it home, my vision is blurred. I have spent approximately $200 dollars all told, and because I’ve been at the Show, I haven’t managed to get to the shops and buy groceries for a couple days. I’m starving. Thank God for Rural Aid—I upend the bag and fish out the packet of craisins.

For the next two days, I lay in bed. I haven’t felt this hungover since the New Years’ rave, and this time I hadn’t had a drop to drink or a single bump of ketamine. And, unlike at that particular rave, at the Show I failed to enter into true oneness with the people. Nor did I experience the world turned upside down, or the flutterings of forbidden desire. Has the show been irredeemably destroyed by commerce, or am I just too old? Maybe carnival wasn’t even that good anyway. If I’d been there in 1565, would I have rampaged around the village eating pork pies or would I have shut myself indoors, grumpy at all the ruckus?

I need some perspective, so I ask a friend to tell me some memories of working at the Show when she was sixteen. She was a showbag girl, and spent an entire school holidays there—twelve hours a day, two weeks straight. She and the other staff wore polyester polo shirts decorated with the Freddo Frog logo, and because the managers didn’t trust the workers, every time a customer paid with a fifty dollar note, they had to hold it up in the air and yell “Pineapple!” Being at the Show every day became “psychedelic.” She said it felt like she’d entered into a “hell-pact” with the other workers, and that because of the collective derangement there was true camaraderie on the job…hence her intense connection with a handsome showbag boy from the suburbs, who became her lover for one steamy summer, where all they did was “fuck, look at his sneaker collection, and watch old hip hop videos in his mum’s house.” In conclusion, she says, she thinks she was lucky enough to have a truly carnivalesque experience. And, after those two weeks were up, she vowed never to set foot in a Royal Show ever again, a vow she has honoured to this day.