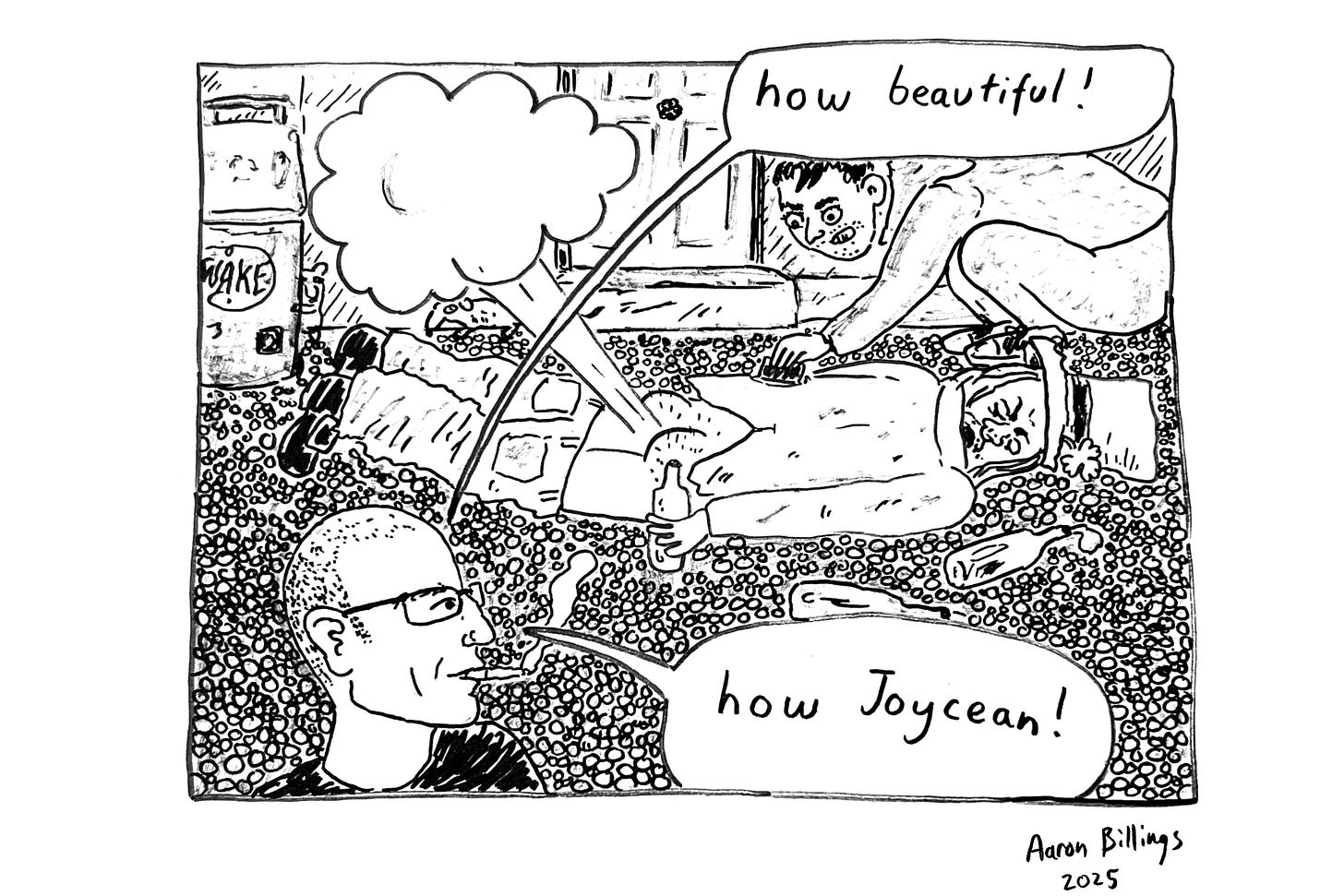

Monday night, Flinders Lane. Rainy. Cold. Midwinter. The man was crawling on the basement floor on his hands and knees in a pair of fishnet stockings, whimpering and moaning. A pig snout was strapped to his nose. Towering over him was a buxom woman, her curly grey hair tied up in pigtails. She was goading, berating, coaxing, beckoning. A few other actors, strapped into corsets and frothy tulle, joined in on the humiliation. The man dragged his kneepads over the boards, making his way towards his dominator. He sniffed enthusiastically at her crotch, then yelped, “Truffles!” I wondered what the Irish Ambassador thought of the scene. He was sitting a few seats back to my left, his face hidden in the off-stage dark. It was Bloomsday, again. Somehow, despite the name, I’d been at Bloomsday for three days now. And I still hadn’t finished the bloody book.

Bloomsday officially falls on the 16th of June. This date in 1904 is when all the action of James Joyce’s 1922 magnum opus of modernist literature, Ulysses, takes place. There are two types of people in this world: those who have read Ulysses multiple times and and those who haven’t read it at all. Notable subcategories in the latter group are those who made feeble attempts but quickly dropped off and those who say they have read Ulysses but are lying (“Among all English-language novels, there may be no greater gulf between how much a work is celebrated and discussed, and how seldom it is actually read,” writes Sally Rooney). There are also the conscientious objectors—people who think it’s white man canon fodder that should be consigned to oblivion. This last group tends to prefer to lie about having read the entire oeuvre of Our Joyce, Alexis Wright.

For those who either haven’t yet had the pleasure or simply just are not, for whatever reason, going to read Ulysses anytime soon, the book can be most crudely summarised as a day in the Dublin life of three main protagonists, Leopold and Molly Bloom and Stephen Dedalus. Leopold is a 38-year-old Jewish man who works as a newspaper ad salesman. Dedalus is a 22-year-old would-be writer who works as a history teacher. Molly is Leopold's 33-year-old wife, a singer who is about to begin an affair with her tour manager, Blazes Boylan. Of course, this summary fails to do justice to the book’s polyphonous style and spurts of stream-of-consciousness nattering. Nor does it address its intertextual erudition, the ultimate example being its structural parallels with Homer's Odyssey. Even plotwise, it’s a severely inadequate precis—kind of like saying the Bible is a story about the son of a carpenter. But you have to start somewhere.

Also, Ulysses is basically a secular Bible at this point. Few other books inspire such intensive scrutiny and theological disputation, all of which culminates each June, when Joyceheads around the world gather to celebrate the tome with reading, drinking, carousing, and general esotericism. As usual, this year was a big one for Ulysses’ global devotees. In Dublin, they had an entire week dedicated to the thing, offering walking tours wherein one could retrace the steps taken by the characters in the book and a “Save the Trees” event about “the parlous nature of Irish forestry in 1904.” In Gibraltar, they commemorated the seaside territory’s significance as the birthplace of Molly Bloom. In Malaysia, they gave away signed copies of Rooney's Intermezzo (say nothing). The Hindustan Times’ Mayank Austen Soofi changed the title of his popular column from “Delhiwale” to “Dublinwale” for the week. In Chicago: “not a recital of scholarship, nor a Joyce-for-purists affair,” but an evening where “words sing, memories ache, and the women speak at last.”

Such is the current state of Joyce devotion. But who are the people so persistently drawn to this 600+ page, 102-year-old epic? What continues to animate the Ulysses cottage industry? And why had I, a person who supposedly loves literature, not read it, despite owning a copy with a quote on the cover calling it “the greatest novel of the twentieth century”? I wasn’t like that girl who spent a year eating every page of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest as an act of feminist protest, although I respected her commitment to the bit. I bloody read that Big Book, footnotes and all. Why not Ulysses?

In Melbourne, a few major Bloomsday happenings were scheduled—mostly on the weekend, as Bloomsday fell on a Monday (the Irish lobby has not yet succeeded in making this a national holiday). There were Saturday lectures and Sunday readings and trivia. There was also a play running, based on the “Circe” section of the book. It was time for Joyce immersion. I booked in for every event.

*

Three days before the truffle-hunting performance, at 11am on Saturday, a frankly obscene time to be on Flinders Lane, I turned up at the Swiss Club, a proud brick building with a red and white flag sticking out over the street. Melbourne’s established Joyce group, “Bloomsday in Melbourne,” was holding their annual Seminar and Lunch. The lift was broken, so I climbed up a few flights of stairs, passing the door to the Edelwyss Bistro & Bar, a fondue-forward spot which reopened last year, and a wooden shield displaying the Swiss Canton Flags and Club donors of 1989. Then I reached a fleuro-lit meeting hall with window alcoves plonked with pot plants.

Steve Carey, one of the event’s organisers, was manning the door. Carey has a PhD in English Literature and wrote his thesis on Joyce under the supervision of the Irishman’s most esteemed biographer, Richard Ellman (this year, in the recursive style typical of Joyce scholarship, a new biography about the writing of the Joyce biography was published—Ellmann’s Joyce: The Biography of a Masterpiece and Its Maker). Carey also currently works as a clinical hypnotherapist at the Contagious Enthusiasm Healthcare Centre in Hampton, where he helps people stop doing things like vaping or drinking 10 cups of coffee a day. At Bloomsday, Carey knew many of the seminar attendees by name. “Put away your ticket, Margaret!” he said, warmly welcoming the woman ahead of me.

A small crowd had settled into chairs in front of a lectern and projector screen. Many attendees were white, in both ethnicity and hair colour. Frances Devlin-Glass OAM stepped up to introduce the day’s two lecturers. She had fine, cropped grey-and-white hair and wore a silky, fitted black jacket and a white shirt, buttoned right up. Devlin-Glass is a major figure in Melbourne Joyceworld: an academic who's been involved with staging original plays based on Ulysses for 32 years now.

There was more than a bit of multi-hyphenate creativity happening at Bloomsday in Melbourne; one of the seminar’s lecturers, Dan Boyle, also had a star role in this year’s Circe play. Boyle spoke about Dublin's historic red light district, the Monto. Next, Manuela Hrasky, a psychiatrist, presented on the sexology of Joyce’s time. She stepped us through the writings of Freud, Havelock Ellis, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, and a whole DSM’s worth of pathological categories and fetishes. The presentation was backed by a slideshow with extremely plain formatting that belied the juicy information being presented about these long-dead figures. Ellis, for example, was “reportedly impotent until the age of 60, when he became aroused by a woman urinating (a response he shared with Joyce).” Imagine your most intimate sexual predilections appearing on a Powerpoint in one hundred years’ time, every proclivity neatly dot-pointed. “Hurst was known to be greatly aroused by [redacted], as well as, infamously, [redacted redacted redacted redacted].” Better throw out those old diaries.

Hrasky confessed that she had only recently succeeded in completing the book, despite having been exposed to it for many years. Her late husband had been a great fan and insisted on reading sections of it out loud to her. “He was particularly fond of Molly's soliloquy,” she said drily. “I don't know whether he was trying to give me a hint or two…” Usually, she'd conked out at “Hades,” but this time she got the whole way through. Hrasky said she thought Ulysses was one of the most psychoanalytic books she’d ever read. In “Circe,” in particular, Joyce had gone against the sexological mores of his time, rejecting obsessions with virility and “toxic masculinity,” as well as antisemitism, misogyny, and religious oppressions. Instead, Hrasky said, he was “urging acceptance of sexual fluidity and the transient nature of gender and androgyny,” as well as staging a new kind of marital union (ENM?). Our hero Bloom, she concluded, was not “virile,” per se, but a man who was comfortable with his feminine self and endorsed love, kindness, and freedom. The crowd clapped happily.

There was something endearing about all this enthusiasm for the bountiful diversity of human sexuality amongst the Joyceans. I wondered if one reason that people loved to read and talk about Ulysses in public is because it’s a genteel way of injecting a bit of libidinal energy into life's doldrums. Some people goon, some people book sugar babies, and some find conjugal inspo at Bloomsday. “Love, soppy as it may seem, is the novel’s great subject,” proposed Merve Emre on the centenary of Ulysses’ publication. Next to me, a woman was rubbing gentle circles on her partner's hand.

It’s worth digressing here to remember that Joyce’s choice of June 16th was not random, but utterly horny and romantic—it was the day of his first date with the great love of his life, Nora Barnacle. Barnacle was working as a chambermaid when Joyce asked her out after seeing her on a Dublin street. The first time they were meant to meet, she bailed. Joyce wrote to her, saying that he “went home quite dejected” and, in a cadence known to anyone who has tried to keep it chill in the DMs, requested another chance: “I would like to make an appointment but it might not suit you. I hope you will be kind enough to make one with me—if you have not forgotten me!” Barnacle decided to give Joyce a shot. As the story goes, when the pair met up, they walked to Ringsend, a quiet area of Dublin, where she promptly unbuttoned his trousers and gave him a wristy.

“You seem to turn me into a beast,” Joyce later wrote in one of his famous letters to Barnacle. “It was you yourself, you naughty shameless girl who first led the way.” Also: “I think I would know Nora’s farts anywhere.” Also (NSFW):

Fuck me dressed in your full outdoor costume with your hat and veil on, your face flushed with the cold and wind and rain and your boots muddy, either straddling across my legs when I am sitting in a chair and riding me up and down with the frills of your drawers showing and my cock sticking up stiff in your cunt or riding me over the back of the sofa. Fuck me naked with your hat and stockings on only flat on the floor with a crimson flower in your hole behind, riding me like a man with your thighs between mine and your rump very fat. Fuck me in your dressing gown (I hope you have that nice one) with nothing on under it, opening it suddenly and showing me your belly and thighs and back and pulling me on top of you on the kitchen table. Fuck me into you arseways, lying on your face on the bed, your hair flying loose naked but with a lovely scented pair of pink drawers opened shamelessly behind and half slipping down over your peeping bum. Fuck me if you can squatting in the closet, with your clothes up, grunting like a young sow doing her dung, and a big fat dirty snaking thing coming slowly out of your backside. Fuck me on the stairs in the dark, like a nursery-maid fucking her soldier…

I want what they had, and so too, I think, did a lot of people at the Swiss Club. (Of course, “what they had” minus the scatology, the years of abject poverty, the painful efforts to find treatment for their severely mentally ill daughter, Lucia, the health complications from drinking min. three bottles of white wine a day, etc etc etc.)

After the lectures, the Joyceans began heading downstairs for their annual lunch. It was completely sold out, and though I had asked for a cheeky journalist ticket, there were strictly no free spots. As I walked towards the exit of the Swiss Club, the other seminar attendees began filing through the doorway into the Edelwyss Bistro & Bar. I peered in desperately, but couldn't see what was happening inside. Who knew what really went on in there, now that the business of the seminar was over? Was the “lunch” really booked out, or had I, a novice, not been attending Bloomsday in Melbourne for sufficient decades to be invited to the annual orgy? What kind of frenzied passions might be stirred up behind that sealed Edelwyss door? Obscene visions flashed in my mind. Circewyss. Bare thighs revealed through gaps in the steam emitting from the bubbling fondue pots. I clutched my copy of Ulysses to my chest and scurried away down the lane.

*

The Bloomsday event on Sunday afternoon promised readings, live music, and Joyce trivia, with Edwardian attire encouraged. It was in Brunswick, in the Celtic Club’s members’ lounge, upstairs at the Wild Geese Hotel on Sydney Road. The Wild Geese, FKA Sarah Sands, was not exactly giving Dublin, 1904, but perhaps a 1904/2024 timewarp. It was freshly renovated, and one got the feeling that the squeaking, swivelling camel leather armchairs and red velvet curtains had arrived all at once, very recently, with a sharp click of a handsomely-paid interior designer’s fingers. Snap. Another cushion there. Snap. And another here. Snap. There. Snap. Here. It was warm at least, and there was Guinness on tap. As my inky pint settled behind the bar, I contemplated whether Joyce would have ordered the “pigs in blankets” with red ale reduction and crispy sage or the jamon croquettes. Maybe the croquettes? He did have Mediterranean tastes.

It was actually a minor miracle that we were gathered for Bloomsday here specifically, in the Celtic Club's new HQ. The organisation has recently been through some of its most tortured and bruising years since its inception in 1887. These were primarily instigated by the sale of the old Club building on the corner of La Trobe and Queen Street which had been, by most reports, a beloved but decrepit boozer. It was open until the early hours, and full of lawyers and journos exchanging tidbits, as well as, in the 1970s in particular, many an IRA sympathiser with a sneaky copy of An Phoblacht, the Sinn-Fein newspaper, and their counterpoints, mystery “affable drinkers” aka ASIO agents (according to Dinny O’Hearn’s history book on the club). But also, as the millennium turned: mounting debts, foul toilets, electrical issues, mostly old boys, a few old girls, problems, problems, problems. Even a sad lot of pokies couldn't bring in enough cash.

In 2016, members voted to approve a $25.6 million sale to Beulah International, a developer group who, if you believe their website, “transcends real estate and property development” to create “transformational spaces and experiences for present and future generations.” Beulah proceeded to knock up a 48-storey apartment building, a hideous Minecraft version of Norman Foster's Gherkin, on the Celtic site, retaining the corpse-like facade of the heritage-listed Victorian building that had housed the Club. The plan had been for the Celtic Club to buy back the ground floors from Beulah. They would presumably reinstall the pub, ignore the gigantic geometrica-clad turd that had been placed atop it, and carry on as before, albeit richer. This never happened. (The old Club space, now a concrete void, is still for sale.) By the early 2020s, there was still no new home for the Club, and intra-member factional acrimony had become so severe that people were filing defamation suits.

Imagine a dysfunctional family inherited millions of dollars and had to decide, democratically, what to do with it, one person explained to me. Think of the most horrible, petty, personal behaviour possible, then imagine even worse, is how another person put it. He said that some of his friends who had formerly been members couldn't believe he was even going to this Bloomsday event—they’d been so repulsed by what they'd seen in the years of Celtic Club turmoil that they had no interest in even being tangentially associated with the organisation ever again. Still, some battle-scarred members weren't giving up faith in the possibility of a new era. Perhaps Bloomsday was just the sort of event that could bring the diaspora back together.

One of the day’s coordinators was a guy doing a PhD on Ulysses at Melbourne Uni, Jasper Harrington. I said hello to him as he bustled about in suspenders. His event’s main drawcard was the opportunity to communally relish hearing Ulysses read aloud. First, Professor Ronan McDonald, current Vice President of the Celtic Club and the Gerry Higgins Chair in Irish Studies at the University of Melbourne, got up on stage in a pork pie hat. He kicked off proceedings with the book's famous opening lines: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.” Then, semi-public intellectual Justin Clemens stepped up to the plate in a Discipline & Punish cap and barrelled through Stephen Dedalus’s emo walk down the beach: “Ineluctable modality of the visible.” Between sets, everything became material for Ulysses references. Trams clanked by outside. Oh, how Joyce wrote about trams!

Trams passed one another, ingoing, outgoing, clanging. Useless words. Things go on same, day after day: squads of police marching out, back: trams in, out.

So true. Dr James Forrester King, a very old Joycehead and gynaecologist—yes, he has published on Joyce and obstetrics—read from “Ithaca” to reverent attention. A man in Edwardian garb, including a costume walking stick, read from a gargantuan special edition as his daughter, a young woman who works at the Clyde, watched him proudly from a couch on the sidelines.

The book really did sound good read aloud, especially in an Irish accent, though the Aussie drawls worked well enough too. But the oral renditions weren’t going to get me much closer to finishing it. I had started a couple of weeks ago and, as a neophyte, was seeking out expert advice. There’s only so much r/jamesjoyce can do.

One kind man at the Swiss Club had told me that he’d just completed Ulysses for the second time in his life, incidentally whilst lying on a friend's yacht in the blue waters of the Caribbean, and that in his opinion, as long as you had the Bodley Head edition, you could start anywhere. Jump right to Molly's monologue, if you like. Skip the notoriously difficult “Oxen of the Sun.” When I mentioned this pick-and-mix approach to some punters at the Wild Geese, however, it did not receive a positive response. No, no, no, they said. It’s a book that takes place over a single day. It's chronological. You should read it from start to finish. Though, actually, there is a school of thought that says you can begin with Book 4… regardless, you won't understand everything the first time round, or even the second, or third, but that's what becoming a Joycean means. When you read it, you make a pact to spend a lifetime contemplating the significance of the Jesuit-schooled allusions and the parapraxes and the shit and cum and big, juicy pears: the extraordinarily contemporary relevance of this book about everything and nothing.

“You haven’t read Ulysses, Dr. Cammy?” the art historian Rex Butler had teased me, pre-Bloomsday. “Shit, man. That’s lowbrow!” I guess I'd put off reading Ulysses properly because the timing had never seemed right, and there had always been books that were more immediately appealing, but Rex was right—those were lowbrow excuses. At the beginning of this attempt, I found myself battling, frequently alienated from what one critic called the “textual situation” of Ulysses: apprehending, rather than understanding, lengthy passages; slogging through sections where only a few lines per page made clear sense. Slowly, I acclimatised. I allowed myself to be buffeted by the Dubliners’ subjectivities, rather than trying to forcibly extract some kind of logical, linear narrative. Then, reading in bed one night as Bloom sat in a pub at lunchtime on June 16th, 1904, eating a gorgonzola sandwich and drinking a glass of red wine, I suddenly found myself right there with him. He's trying not to think about Molly and his impending cuckolding. He knows she’s going to bed with Blazes Boylan in a couple of hours. He chews and swallows. Looks at the “bilious” clock. Starts to cry a little, but tries to hide it: “Hope that dewdrop doesn't come down into his glass. No, snuffled it up.” My own eyes grew hot and wet. Oh, Bloom!

So many books of our era speak in a voice that is clipped, flat, cool, and borderline affectless—a voice protected by a precisely managed, ironic distance, even as it tries to escape itself and scrabble towards something real. Ulysses is an anathema to this sensibility. It broadcasts a florid, flatulent modernism. At times, I found this almost embarrassing to encounter. Why, for example, is everyone in Ulysses farting constantly? (I guess because everyone everywhere is farting constantly, unfortunately.) But my chaste, repressed cringing ultimately gave way to pleasure as Ulysses wandered from character to character and style to style. It’s romantic, pompous, deflationary, frequently hallucinatorily silly. At one point, Bloom essentially undergoes sissification and births eight children (Andrea Long Chu eat your heart out). It’s funny. There is literally a character called Cunty Kate. It’s gross. Blazes Boylan, that dastardly piece of shit, asks a guy to smell his finger after he’s been in bed with Molly (or does Bloom just imagine this?).

At the Celtic Club, the afternoon turned to evening. Another pint of Guinness, please. A man in a shamrock green suit jacket warbled “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” a capella. During trivia, someone said they didn’t want to be on Clemens’s table, because they didn’t want him to know how little they knew about Ulysses. Another pint. Cigarette with Clemens and co., who say that the Celts used to fight naked, stripping off and running full tilt ahead into battle with pasty white limbs bared, a kind of confidence bluff or ghost flesh fear tactic. Now we just have Irish-Australians trying not to argue about real estate.

*

I didn’t make it to the post-Celtic Club Bloomsday kick-ons, but I showed up at fortyfivedownstairs on Monday night, the fated June 16th, for the play. There were a few familiar faces—Frances Devlin-Glass (wearing a military jacket) and Steve Carey in the bleachers, Dan Boyle with face painted on stage—plus a decent smattering of civilians. We sat facing the stage in the centre of the room. The lights changed. The speakers played an Acknowledgement of Country referencing Joyce’s anti-British sentiments, as well as trigger warnings for herbal cigarettes and haze. A reggae song came on. The thespians strode about in their corsets and tulle, domming the lad playing Leopold.

After the bows, when the applause petered out, I walked into the night air and up to Spring St. Waiting at the tram stop, as a couple of teen girls wearing fake eyelashes and unconscionably tiny tops shivered and showed each other phone things beside me, I experienced a sense of relief. Maybe I was being antisocial, but there was a fatiguing quality to the insistent publicness and collectively jovial spirit of all these events, despite this also being what made them galvanising. So much of the book is about the texture of interior life—about private thoughts, and how they follow one another in quick, semi-random succession (or, in Molly’s case, as punctuationless torrent), and about simultaneous, untouching private sadnesses. Stephen Dedalus’s dead mother haunts him. Leopold and Molly’s dead baby son, Rudy, haunts them. For now, the fan fic and fanfare were behind me. Praise be. Bloomsday was over, and I could finally get back to reading Ulysses.