On the news, I hear that Australia’s population has just passed 27 million. It is 9.30am—a humid Thursday morning. I’m sitting on a bench opposite the donut cart at Preston Markets. The report is playing over a radio outside the borek place. An old man wearing a sailor’s hat listens while drinking a coffee and rubbing his knee. “The population milestone comes thirty years earlier than projected,” the announcer continues. “Which some demographers take as a cause for great concern.”

Someone calls my name. I turn around and see π.o. (pronounced Pi O) and his partner, the artist Sandy Caldow. Despite the weather, π.o. is wearing his usual get up: work slacks, a polo shirt, and a tweed jacket, with his reading glasses resting on top of his unruly gray hair. π.o. is, according to π.o., one of the most brilliant and important poets working in Australia. I happen to agree. I wrote my Honours thesis on 24 Hours, π.o.’s 740-page epic poem about the coffee shops and gambling joints that once lined Fitzroy’s thoroughfares. π.o.’s father ran several such coffee shops, and the poet spent his formative years working in them, back when the neighbourhood was still considered a migrant “slum.” In the late eighties, the cafes began to shutter, one after the other, as a younger, wealthier crowd began to move in. π.o. spent the next decade sitting in the shops taking notes, transcribing what he calls “the migrant dialect” that was spoken amongst the clientele, who were, like the shops, disappearing from Fitzroy as the rent went up. For example:

Howw yoo ken

Living in - dis kuntri?!, a bloke sez:

Wun e’wwa HOT.

Wun e’wwa kolt. Wun e’wwa chaynch.

Awl da Aastraalia:

G’e Fuk! . G’e Fuk! . G’e Fuk!

Howw yoo

ken living...?!

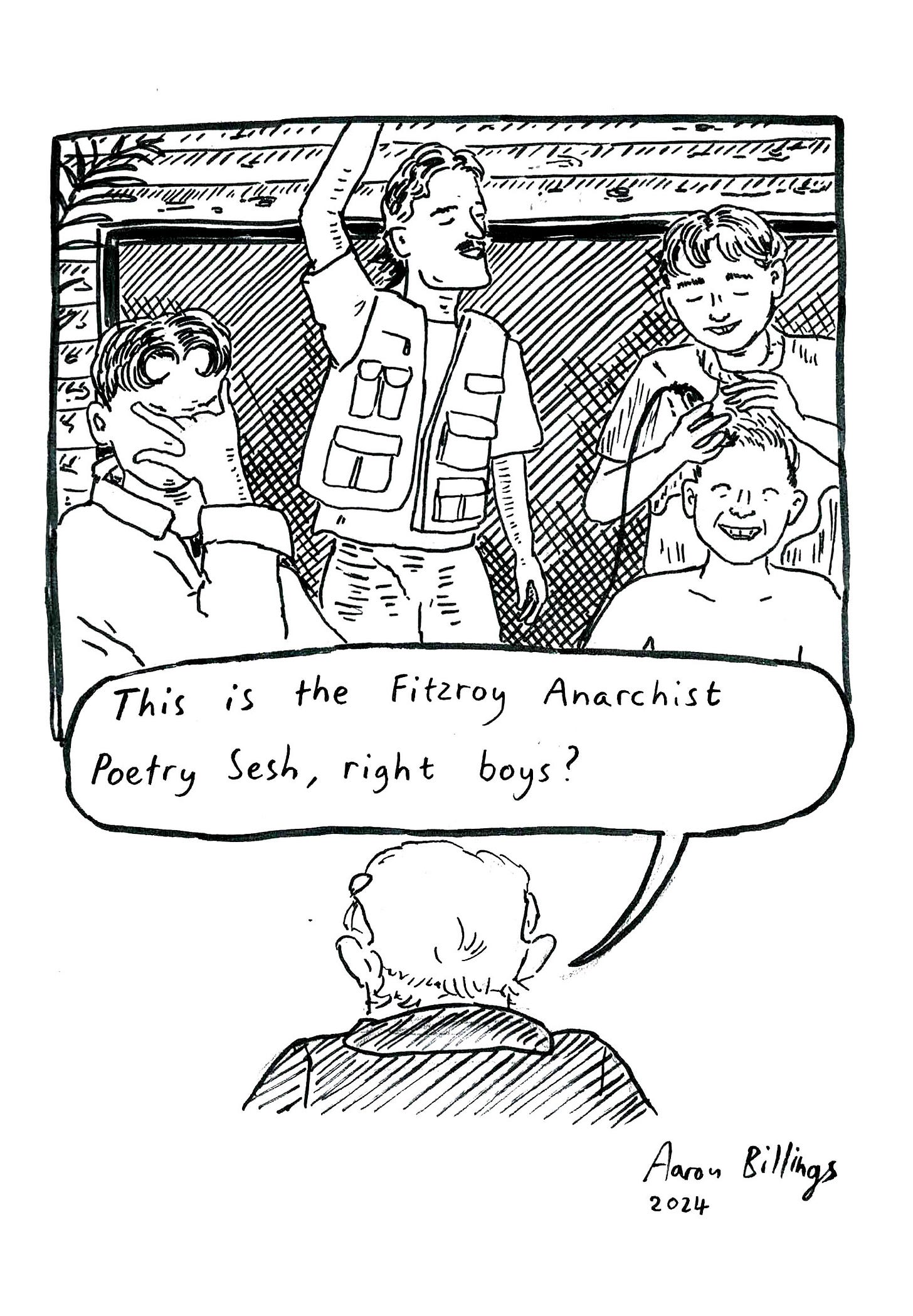

π.o. doesn’t live in Fitzroy anymore, but he’s still a regular presence, a stalwart, a genuine local icon. You’ll see him pottering up and down Smith Street or Brunswick Street, delivering his books to book sellers and chatting with old friends. Or you might see him reading at some book launch or gig. I remember the first time I saw him perform at a poetry night in Carlton. He came on stage after a genteel poet from rural Aotearoa/New Zealand, who mumbled a few sonnets about seagulls while looking at his loafers. π.o. shouted out a poem with just two words, “clit” and “cock,” which he repeated in varying combinations in his booming staccato. I was twenty-one and left humming with the possibilities of poetry.

π.o. is also one of Melbourne’s foremost literary hecklers. If he doesn’t like your poem, he’ll let you know mid-stanza. He is a sharp critic, too, and does not shy away from a good beef. He had a long-standing one with Les Murray, whose bushman savant aesthetic π.o. found reactionary and insincere. In an essay published in the Sydney Review of Books shortly after Murray died, π.o. recalls how the first time he met Les, the grand old poet told him, with some condescension, that he was sure that π.o. would some day “make a big splash” in the scene. “I remember turning to him and thinking he better not jump in the pool or there won’t be any water left,” π.o. writes.

The combative public persona eases when hanging out with π.o. one on one. He smiles with a deep squint and laughs often. His whole being oozes enthusiasm, and he talks about the Situationists or Baudelaire with the same zeal as an undergraduate who has just read Les Fleurs du mals for the very first time. He is in his seventies and continues to publish magazines, host readings, write books, perform poems on the radio. His undimmed belief in poetry’s revolutionary promise is infectious. He is always scheming something new.

A while back, for instance, during one of the brief reprieves between pandemic lockdowns, I saw π.o. on the corner of Johnston Street and Smith Street, and I went up to say hello.

“I thought you were in New York,” he said.

“I was but I’m home now,” I said.

“Welcome back to the centre of the world,” he said, gesturing at the 86 tram. “You can start writing about me again.”

“Oh yeah, what are you working on?”

“I’ve invented a way of writing that infects language the way a virus infects the body,” he said. “It’s brilliant, like pandemic Oulipo.”

When I saw him again the next time, at Brunetti's, I asked how the virus poetry was coming along. He told me that he had perfected the form, and was now using it to compose a book-length poem about how gentrification arrived in Fitzroy via La Mama and the Pram Factory, two theatres that opened in Carlton in the sixties. These were hotbeds of avant-garde experimentalism and leftist revolutionary zeal. They gave rise to the bohemian scene chronicled in Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip, which became a kind of aspirational blueprint for how to be young and free (and white) in this city.

But for π.o., that scene meant something else entirely.

“When the theatres opened, it was the beginning of the end,” he told me. “The gentrification flowed out of those places like lava, or a virus, and into our streets. I can map it. I could show you.”

And then, a little while later, we made plans to meet at Preston Markets.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Paris End to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.