Design Files Mindset

Are Nightingale’s ethical, sustainable, beautiful apartments an answer to our housing crisis? Sally Olds needs to know.

When starting this piece, I sensed immediately that I was leaping into the centre of a decades-old brawl between the Greens and Labor, Labor and the Liberals, between local councils and state governments, between developers, financiers, renters, owner-occupiers, property speculators, public housing advocates, non-profit wonks, Community Housing Providers, real estate agents, academics, architects, communists, YIMBYs, NIMBYs, builders, designers, and landlords. Except for a vague desire for cork flooring and a cooktop other than a Chef brand gas stove—and, yeah, sure, a rental I could stay in for more than a year—I did not have a dog in this fight. I was confused about the situation at large, and resigned to my own circumstances as a life-long renter. In short, I was the perfect target for Nightingale, which promises to help people like me get into home-ownership. I read through their website with mounting excitement, and quickly, I was emboldened. All that stood between me and my forever home was $600,000 and my complete ignorance of anything to do with housing. And that’s how, one day, I was scrolling idly through The Design Files, nursing petty grudges towards home-owners delighting in their terrazzo kitchen islands, and the next I was reading a 66 page report on the Public Housing Renewal Program. Now, I still want cork floors, but I also want to raze the entire Victorian housing system to the ground.

Nobody quite knows who to blame for the mess we’re in—is it Dan Andrews, COVID, John Setka, south-side property moguls?—or how to get out of it. The mess is that practically nobody on a mid- or low income can afford their rent right now. Interest rates are rising, and landlords are either struggling to afford their mortgage repayments and jacking up rents to cover it, or pretending they can’t afford them and jacking up rents anyway. Everyone I know is getting evicted, or waiting for it to happen. I’m on my third rental in two years.

In terms of cleaning up said mess, opinions differ vastly. The Federal Government thinks it’s a matter of supply, and have been trying to get a bill through parliament to this effect: they want to build more private housing, and they claim to want more social and affordable housing, too. By this logic, the extra housing both provides more homes and drives down the cost of real estate. Whether that works is another matter entirely. As Jennifer Kulas—an affordable housing advocate and development manager—put it to me when I chatted with her recently, “I think it’s a convenient distraction to say that supply is the issue. Think about what a glut of bananas you need to have before they drop to $2 a kilo…One in ten homes in Australia are empty right now. Like, give me a break.”

The Greens are not into the supply thing, either. They want a rent freeze, longer leases for renters, strict regulation on investment properties, inclusionary zoning—i.e. a mix of community and private housing in each new development—and greater funding for public housing. Both the Greens and the Coalition voted to delay Labor’s bill. Some say the Greens are the only ones making the kind of macro structural proposals that will have an impact; others think Max Chandler-Mathers is everything wrong with our generation. The Coalition have their own nefarious reasons for blocking the bill, which have something to do with, uh, wanting to let people withdraw super to buy a house?

Meanwhile, in Victoria, the Andrews government is bullish on supply. As part of its Big Housing Build—a cheery, childishly titled scheme that replaces the former, more sombre Public Housing Renewal Program—the State government now has the power to bypass local councils to fast-track development. This is a controversial move. In the case of a sped-up Preston build (by the Nightingale-adjacent developer Assemble), the Darebin Council and residents are furious. Nearby suburbanites say they did not get to have proper input and that the 15-storey building will significantly increase congestion and overshadow their homes.

By this point in my research, I was mad and getting madder. I was emailing local councils, joining Facebook groups. And then I learned about what’s going on with social housing. Social housing is an umbrella term that encompasses both public and community housing. The terminology is extremely confusing, and worth spending a little time hashing out. (Wake up sheeple, they want you to be confused.) Public housing is not the same as community housing. Public housing is owned by the State, and provided to the lowest-income members of society. Public housing rent is capped at 25% of whatever your household earns. Community housing, on the other hand, is managed by not-for-profit organisations known as Registered Housing Agencies. Community housing rent is capped at 30% of your household’s total income. To add in another variable, it may also be calculated as a percentage (usually around 75%) of whatever the market rate is—which, frankly, is unlikely to be affordable when that rate is obscenely high. To access either a community or public dwelling, you have to go on the waitlist, which is currently around 59,000 households strong. Even if you’re in the priority section of that list, it may take two years or more to get a place. More on this later, but most Nightingales contain at least some community housing (not public housing).

Here’s the bottom line: public housing is cheaper for tenants than community housing. There are still far more public than community dwellings in Victoria, but the supply of public housing has nevertheless been in decline year in, year out, while the community housing sector grows. As part of the Big Housing Build, Labor is seeking to knock down existing public housing estates—many of which have been allowed to fall into disrepair—and rebuild and manage them in partnership with private developers and Community Housing Providers. In a few instances, the Victorian government is using a Ground Lease Model, in which public land is loaned to housing agencies who develop and manage the dwellings for forty years, at which point ownership reverts to the State. The Ground Lease Model is a little better, but some say it’s also damage control—a cover-up of the fact that the Victorian Government is currently selling more public land to the private sector than any other state in Australia.

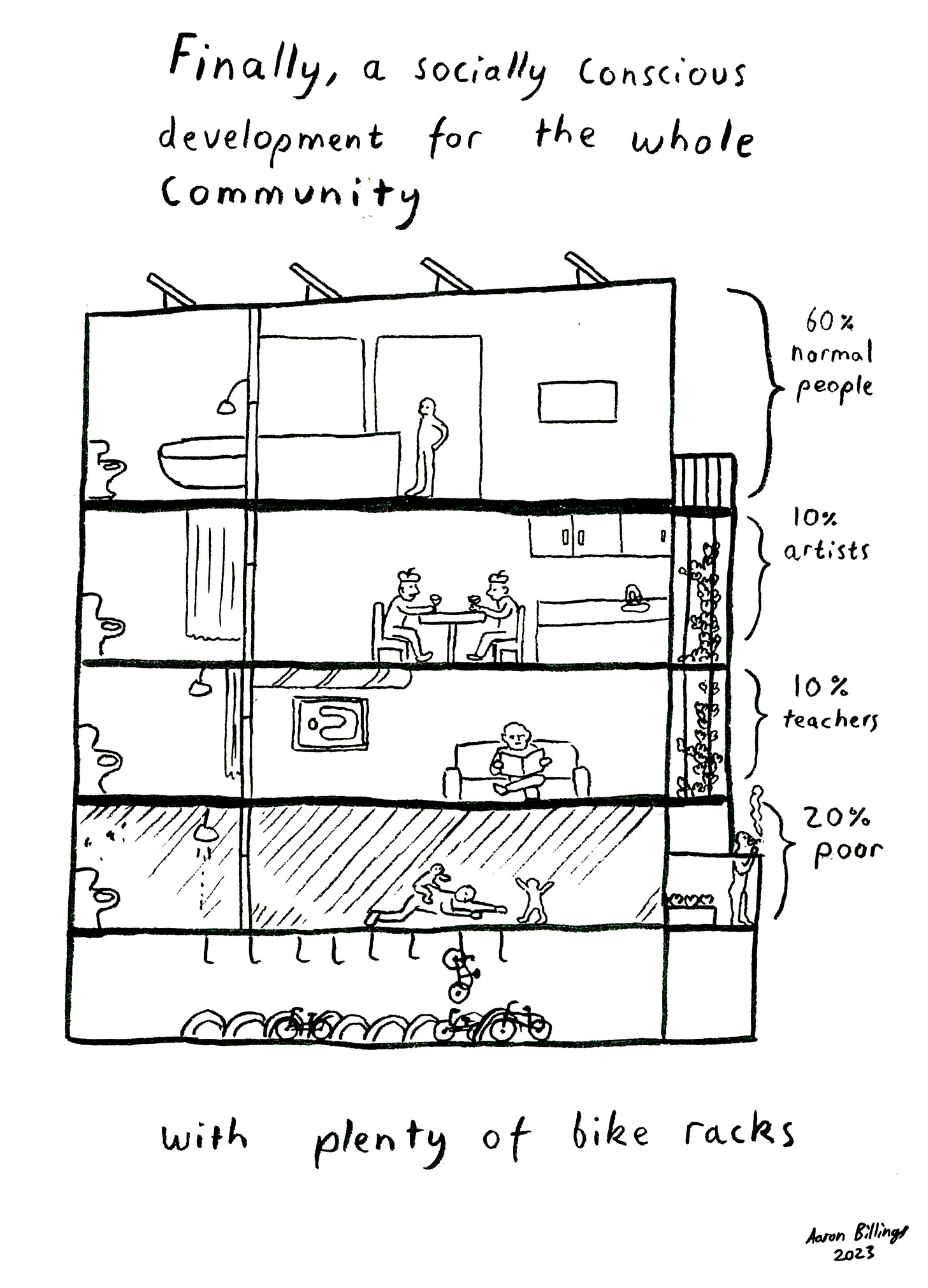

One casualty of the Big Build/Renewal program is Walker Street in Northcote, a former public housing estate. The land was sold to private developer MAB, tenants were evicted and rehoused elsewhere, and the 87 existing dwellings were bulldozed. It is being redeveloped as “mixed tenure,” which means that instead of 100% public housing, it will be about 41% community housing and 59% private residences—some of which are selling for seven-figure sums. Tenants have the right to return once the build is completed, but will they want to come back, years later, when they’ve put down roots elsewhere? One former tenant, William Gwynne, points out that in the new development all the community housing residents will be clustered at the back. They used to face the Merri Creek; now they’ll be looking over High Street. Unsurprisingly, water views are for rich people.

*

Can’t a girl have both? The creek views, and the good politics? Is that so much to ask? Under the current set-up, it feels like you have to choose one or the other. You can have your charming apartment in the inner-north with indoor/outdoor green space and solar panels, but you’re going to have to pay serious money for it. Or, you can have your staunch, lived commitment to public housing and the overthrow of the capitalist oligarchy, but you’re going to be living in Sunshine North in a dank 1950s granny-flat. Socialist Alternative isn’t known for its design nouse. Design Files types aren’t renowned for their materialist politics. The impasse is real.

Enter Nightingale. Nightingale is a not-for-profit Melbourne-based developer that seems to have it all. Since 2016, Nightingale has been building beautiful, environmentally friendly, and affordable mid-rise apartment blocks in Melbourne. In 2017, they had roughly twenty apartments. In 2023, they have 1000. They’ve recently expanded into other capital cities, including Perth, Adelaide, and Sydney, and are looking into several other sites across Australia. As Nightingale CEO Dan McKenna told me recently, “We will be as big as we need to be.” Then, a more temperate addendum: “If everyone else starts doing what we’re doing, then we don’t need to exist anymore.”