This is the first instalment of a two-part series.

I’m sorry to say it, but people don’t sit around fantasising about the National Tertiary Education Union. They don’t get drunk and describe, in covetous detail, the physiques of members of the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance. Nobody downing pints at the Clyde is fetishizing the industrial history of the Civil Air Operations Officers' Association of Australia. People do get a little worked up about the Retail and Fast Food Workers Union, but still—the only union in Australia that is really, truly fodder for impolite dinner table conversation is the Construction, Forestry, and Maritime Employees Union, better known as the CFMEU.

A representative conversation might go like this:

Apolitical twink (in midriff top): “I matched with this tradie on Grindr the other day. He was so hot. He had massive quads, but he only wanted chem sex so we didn’t hook up.”

White-collar union twink (in a “God Forgives, the CFMEU Doesn’t” slogan tee): “I loved that merch they made in lockdown. The CFMEU face masks? J’adore.”

Local Greens councillor (accepting a Hazy IPA): “The stereotype of the thuggish CFMEU member is disrespectful to the honest, hardworking men, women, and nonbinary people of the union, and it is largely perpetuated in media beat-ups.”

Union they/them (wearing Blundstones): “Yeah, the corporate media loves to vilify CFMEU. The members of CFMEU are extremely militant, and we, as unionists, need to stand behind the rank-and-file. Without the CFMEU, what have we got?”

Local Greens councillor (nodding): “And what about the developers? Where’s the scrutiny on them?”

Labor staffer (in pastel button-up): “Am I missing something here? John Setka is a convicted domestic abuser and the culture of the CFMEU is deeply anti-women. And that’s before the bikies even come into the picture.”

Apolitical twink: “Yeah but did you see that neck tatt Setka just got? Slay.”

The CFMEU has an undeniable libidinal charge. Crikey columnist Guy Rundle feels it—he wrote recently that he once pitched the idea for a nude tradie calendar to the CFMEU. Girls and gays feel it as they stroll past building sites or packed city pubs at knock-off time. Sensible white-collar workers feel it in the quivering of their atrophied industrial muscles as they try to raise disputes or bargain for a micro pay rise. Even those most neutered of creatures—politicians—feel it. Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan is married to a former CFMEU official, after all, and her predecessor, Dan Andrews, never missed an opportunity to pose in a hard hat as he spruiked the Big Build.

Construction is the division that receives the bulk of the nation’s attention. (The CFMEU also represents textile workers, who just don’t get the same air time.) Nationally, across all divisions, the CFMEU has a membership of just under 130,000. It represents approximately 30,000 construction workers out of Australia’s 1.3 million. The history of the CFMEU is hard to summarise, because—as with all good union lore—it’s full of amalgamations, schisms, and acronyms. It’s like…so, in the 1990s, the BLF became the BWIU (kind of), which had already amalgamated with ATAIU, and then BWIU became the CFMEU, which, for a while, picked up an extra M from the MEU, and then the CFMMEU amalgamated, in 2018, with the MUA and TCFUA, before dropping the M in 2023. Got it?

The big ones in there are BLF and BWIU. The Builders’ Labourers Federation was a union that began in 1911. In the 1960s and early ‘70s, it became notorious/beloved for its militant NSW branch. The branch was led by a long-haired Communist Party member named Jack Mundey, whose rank-and-file membership famously implemented and defended a host of “green bans.” These were bans on demolition and construction that would destroy parklands, housing, and community infrastructure, and included shutting down a multi-million dollar development of high-rise towers that would have levelled what is, today, Sydney’s most charming bobo area, The Rocks. The NSW branch faced extreme pressure for its militancy from both inside and outside of the union, which led to it being forcibly dismantled, and the BLF as a whole deregistered in 1972. Four years later, under new leadership, it was re-registered. It was then deregistered a final time in 1986 amid a Royal Commission into corruption, which found that then-secretary Norm Gallagher had accepted around $100,000 worth of materials gratis for his beach house from a building company. The Building Workers' Industrial Union—a long-standing enemy of BLF for reasons of internecine communist drama—absorbed much of its membership. This base then became the CFMEU. Some say the CFMEU inherited its radicalism from Mundey’s BLF; others think it has more in common with the Gallagher era. Either way, the CFMEU’s historic connections to the BLF’s storied shit-stirring are part of what gives the union its hardline reputation.

But there are some key differences. When you think of unions, you probably think of twentieth century-style strikes: linked arms on the picket line; a ragged cheer going up from throngs of grime-streaked blokes at the factory gates. If that’s what comes to mind, update that vision to the twenty-first century reality of lengthy Zoom meetings, online petitions, and strained politesse around an office table. Nowadays, you can only legally strike while negotiating an Enterprise Bargaining Agreement (EBA). You also have to apply for specific protected actions—this could be a refusal to handle cash, a stop-work for a particular period of time, or any number of other options—which Fair Work has to approve. If that all pans out, you still have to give your employer three days’ notice before downing tools.

The CFMEU doesn’t mind breaking these rules in service of its membership. In 2012, for instance, CFMEU members working on the Emporium build in Melbourne’s CBD struck for four days over safety issues, blockaded the site, sparred with pepper-spraying police, and ultimately earned millions of dollars in fines for what was, officially, an illegal strike. Most Australian unions would never countenance such behaviour, even if they could afford it. John Setka, the up-until-very-recently secretary of the Victorian-Tasmanian division of the CFMEU, thinks otherwise. “If they keep illegalising [sic] us to do our job, then of course it'll put us on the wrong side of the law,” he has said. Sally McManus, secretary of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, has defended the CFMEU’s renegade behaviour in the past, stating: “It might be illegal industrial action according to our current laws, and our current laws are wrong.” This is why our Blundstone-wearing union-pilled they/them—alongside many white-collar unionists with no links to the construction industry—are ride-or-die for the CFMEU: this union represents the last bastion of real worker power in the country.

Not all the attention is glowing, though. A little over a month ago, a kind of super-group of journalists from Nine-Fairfax’s The Age, 60 Minutes, The Sydney Morning Herald, and the Australian Financial Review dropped “Building Bad,” a series of reports on alleged corruption, bikie-infiltration, and organised crime within the union. (60 Minutes, which presented a highly-saturated, B-grade rendering of the claims, airs on Sunday nights just after amateur-hour home reno show The Block; punters were primed to receive the bad news about Australia’s most revered/reviled profession.) I won’t rehash the claims here; you can read the ins-and-outs of these reports yourself. But to give just one example of the allegations, the NSW CFMEU state secretary, Darren Greenfield, has been accused of taking a bribe from a developer in exchange for the union’s support on a building project. In grainy stills, Greenfield seems to reach under the table and accept a wad of cash from the man seated next to him. He then appears to place the cash in a desk drawer. It’s all very The Wire.

In the wake of the allegations, tensions that have been building for years have come to a head. John Setka, who was convicted of harassing his ex-wife, Emma Walters, in 2019, and who refused to resign over it, stepped down. Darren Greenfield’s son, Michael (also accused of corruption) has resigned, though so far the elder Greenfield is still in his position. Shortly after the stories broke, politicians began threatening the drastic action of appointing an external administrator, who would oversee the union's operations and investigate the allegations. The Fair Work Commission nominated Mark Irving KC for the job. Meanwhile, the CFMEU had appointed their own choice, Geoffrey Watson SC, who began the process of sifting through the union’s business. Minister for Workplace Relations, Murray Watt, gave the CFMEU a Friday 5pm deadline to agree to enter administration on the government’s terms. It was a false choice; if they didn’t consent, Watt would draft a bill that would force them into administration anyway.

That’s exactly what happened. National Secretary, Zach Smith, replied with a “maybe” at 5:09pm. (What was he up to in those nine minutes? Carefully selecting the right emojis? Chewing his fingernails and waiting to press send?) Minister Watt was pissed. He spent the next days hyperactively drafting the bill, and—at the time of writing—has just pushed it through Senate by wheeling-and-dealing with the Liberals. The bill now needs to pass through the Lower House. If that happens, Watt will have the power to place all branches of the Construction and General Division of the CFMEU into administration, including those without any allegations of misconduct. The administrator will assume the role of union boss. He can spend the union’s money, decide what to do with its property, and hire and fire people. The Greens opposed the legislation, calling it “an unprecedented attack on the rule of law.” In retaliation, some elder millennial in the Labor party made what they probably think of as a “dank meme” in which John Setka is caricatured as a puppet-master pulling the strings controlling Adam Bandt and his crew.

From the outside looking in, it’s hard to tell how much of this trouble has to do with the CFMEU’s pugilistic attitude towards bosses, employer associations, the government, and the law, and how much has to do with the, well, large men in leathers who aren’t not bikie-adjacent. Everyone seems to be invested in obscuring this difference. The ABC reported this month that the CFMEU broke workplace laws on 2,600 occasions over the last twenty years, without clarifying how many of those breaches were occasioned by routine industrial action and how many were related to incidents of violence or corruption; a casual reader could be forgiven for thinking that unionists have committed 2,600 individual acts of violence or bribery. The Liberals are calling for deregistration. The CFMEU is calling it a classic stitch-up. The Paris End was compelled to enter the fray. I donned my hard hat and got to work.

*

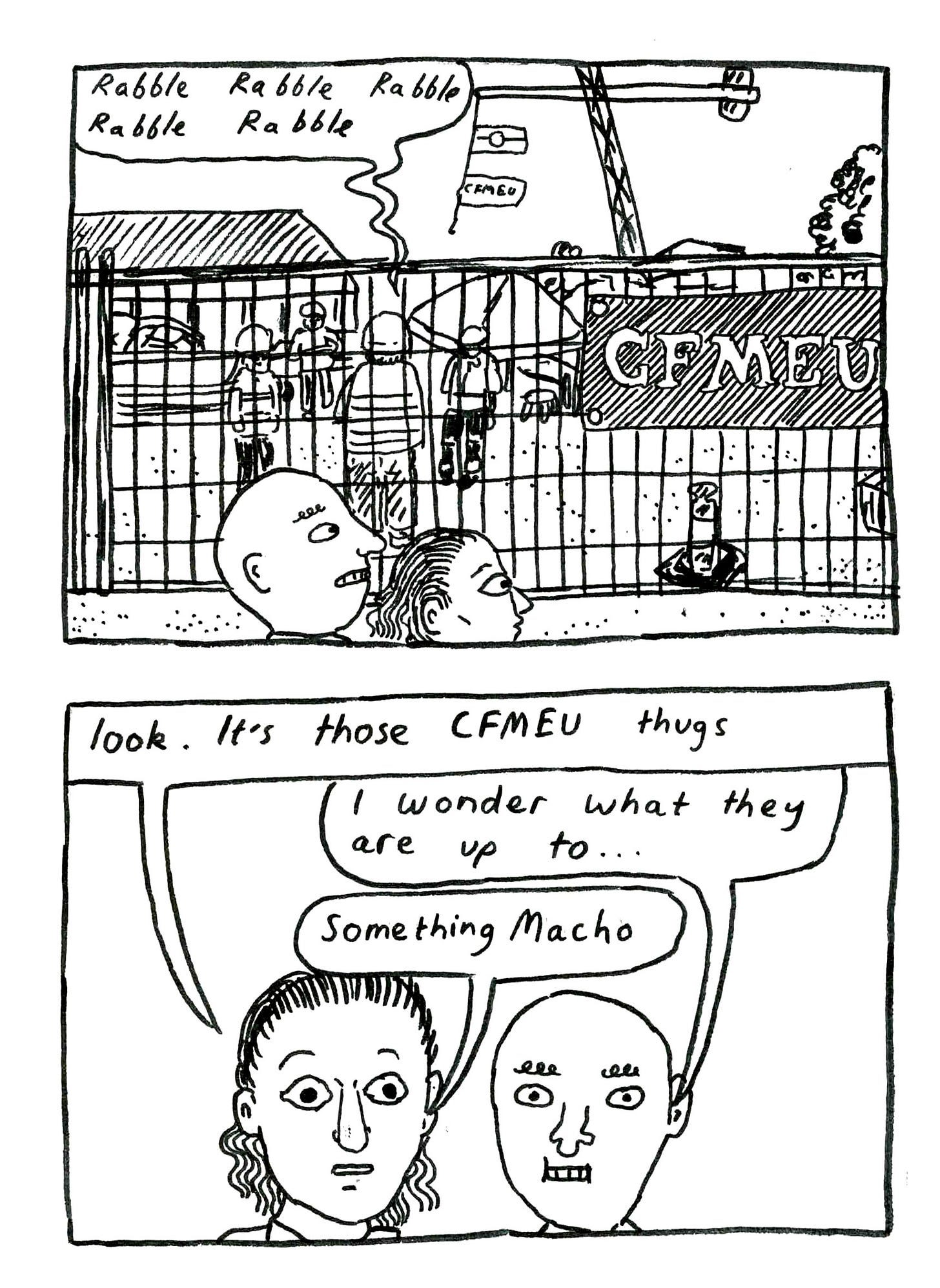

In all of this furore, there has been comparatively little attention given to the rank-and-file members of the union, apart from some afterthought paternalistic platitudes about what’s best for the workers. So, to begin with, I wanted to talk to some actual CFMEU members. They’re not hard to find. My co-editor, Cam, and I walked to the biggest Big Build site we could find in the city—the new Town Hall Station—and began pestering people in high-vis.

The first group of orange-clad workers we approached pointed to another group of orange-clad workers and told us to talk to the “boys over there” in the “MC jackets.” The MC men shook their heads and told us to speak to the “blue hats.” We walked up Flinders Lane and spied a man in a bright blue helmet walking by with a companion. We scampered across the road to intercept them. “Er, hi, we'd just like to ask a few questions…” Blue hat's companion laughed, shook his head, and tapped his shirt logo, which read “ETU.” “ETU, ETU, can’t talk,” he said. As we walked alongside them, the man in the blue hat fobbed us off to two men passing by in the other direction: “There ya go. They’re delegates, ask them.” We spun around to fall in step with the delegates. We asked the man whose hat had the most stickers on it if he had anything to say. He replied: “I’d really love to spill the beans, and I’ve got a lot of beans to spill, but I can’t talk to youse.” They told us that the “higher-ups” had instructed them not to: “We’ve got a lot to consider right now.” We tried a few other sites in the city, but no one would speak. The coordination was impressive—the union had closed ranks.

Taking my search online, I messaged a Facebook page called “Rank & File: Hands off the CFMEU.” I sent my phone number and received a text a few hours later from a man called Tom, a retired construction worker who worked in the industry for eighteen years, and a current member of the CFMEU (when you retire, you can maintain your membership for a nominal fee). We met on a Tuesday morning at a large chain cafe next to a train station. Tom had marshalled serious evidence in preparation for our meeting: crinkled plastic A4 sleeves stuffed with print-outs of articles, timelines, and quotes he’d compiled from politicians and the media. Throughout our conversation, he rifled through the pages, fact-checking himself and pointing out interesting details.

Tom didn’t look old enough to be retired, but he told me that construction is a young person’s game. People go into the industry wanting to set themselves up for life. They work hard, then, if they’re lucky, exit relatively unscathed.

“It’s a dirty, dusty, dangerous industry,” he said. “Sometimes I’d come home after labouring and have dust coming out of my nose. I was told to go home one time ‘cause the bosses realised they had me digging in a spot with heavy metals. I had to throw out my clothes.” Tom has almost been killed on site twice. “Maybe three times. I feel like I’m forgetting one...”

When Tom first started out it was with a labour hire company doing domestic renovations. Then the union shop steward at the company suggested Tom get his “tickets,” or, licences. He gradually received the necessary qualifications to drive a forklift, as well as operate scissor lifts, elevated work platforms, and hoists—a kind of makeshift lift for transporting workers on high builds—which gave him access to better paid jobs. (CFMEU members can do all this training for free through the union.)

Many workers are employed by labour hire companies, who have labour-supply contracts with particular building companies, meaning that the workers themselves have very little job security. Whereas in retail, for instance, you may work at the same shop for years, in construction, you may work at three or four or ten, or even more, different job sites in a year. This baked-in itinerancy lends itself to both exploitation and to unsafe working conditions; you don’t know what you’ll be facing on site from one day to the next.

Tom regaled me with a best-of selection of employer sins he’s witnessed over the years—just a few out of dozens of possible examples. One time, Tom was driving a hoist that stopped twice throughout the job, leaving workers stranded mid-air. “It was a cheap-arse hoist," he said. "It sometimes wouldn’t start in the morning.” On that same site, a worker reported the employer to WorkSafe because they had no lighting in the stairwell—an OHS risk, and a violation of the law. “The company did not want to pay the cost of temporary lighting.” On another job in Canberra, he was underpaid by ten dollars an hour for a whole month before he realised what his rate of pay was meant to be. He got in touch with the bosses and threatened to bring in the union. “They said, ‘oh no, no need to bring in the union.’ The company shat itself.” Tom took a sip of his coffee. “It’s not like any other industry. Any of the basic stuff that most people expect to get from their employer, you have to fight for. You have to scrabble for everything.”

I read out a quote that I’d come across earlier that morning in an Australian Financial Review op-ed: “Safety has been commonly weaponized by the CFMEU.” According to the author, the CFMEU had used safety as a pretext to muscle onto work sites and, once there, “foster discontent,” incite strikes, bully employers, and more.

Tom scoffed. “The CFMEU have had to make safety an issue because most bosses couldn’t give a shit. They do a matrix for themselves: ‘Oh, the chances of something happening or us going to court are so low that we don't care.’ Companies have this mentality that they’re feudal lords: we pay you good wages, now we own you. They want you to just shut up and work.” According to preliminary stats from Safe Work, in Australia, ten construction workers have died on the job so far this year. Last year, it was forty-one workers, and construction had the second-most fatalities of all industries in the country. There is all kinds of evidence—anecdotal, empirical, statistical, dry research paper—that union sites are safer than non-union ones.

I asked Tom what he thought was driving the unsafe working conditions in construction. He laughed a long, deep, cynical laugh.

“Companies want to get bigger and bigger. They cut corners. Big companies will give their builders a bonus to deliver the building on their timeline, so it’s 'push, push, push' to deliver it on time. The industry lends itself to corruption. I'm not saying the officials—I'm saying the industry.”

As for the officials, Tom said he didn’t doubt that some individuals in the union were corrupt, but pointed out the double standards at play.

“If it’s an institution like the police, they say, ‘Oh, it’s a few rotten apples.’ They don’t shut them down.”

He thought the response from the Labor government was about optics; they’re taking the opportunity to look strong, while the opposition is invested in blowing out the allegations to make Labor look weak and complicit. Vic Labor is also on the hook for delivering the projects comprising the Big Build, which has long since exceeded its original timelines and $90 billion budget. Some analysts have drawn links between the Big Build and the housing crisis, with recent modelling from the Grattan Institute suggesting it’s driving up inflation by monopolising labour, materials, and funding. Better to scapegoat the CFMEU, perhaps, than cop to poor planning. “It’s like, Labor can't do anything about the cost of living crisis. But they can destroy a union which actually gets pay rises for its workers to deal with the cost of living crisis.”

Others have claimed that—well, actually—it’s the CFMEU’s pay-rises that are inflationary. A recent AFR headline asked: “Is CFMEU the reason none of your friends can buy a house?” The article mentions a report commissioned by the Master Builders Association, an organisation of building, housing, and construction employers, and a long-standing nemesis of the CFMEU. The report found that the conditions mandated by the union in Queensland were decreasing productivity by at least a day per week. MBA boss Paul Bidwell gave an example of the CFMEU refusing to approve a 2am concrete pour, which held up work for several days until the daytime temperature was cool enough to proceed. (Scandalous—if you ask me, those workers should have been forced to perform dead-of-night manual labour.) So, for the MBA, Tom thought, “it’s about squeezing more productivity from the industry.”

As he gathered his papers, unzipped his backpack, and slipped them in, Tom mused on boss mentality. “The bosses expect everything to go their way,” he said. “Over the last decades, they’ve atomised the workers, made it harder for workers to strike. But there’s one union that sticks out like a sore thumb, so they’re gonna try to hammer it down.”

*

While writing this piece, I developed a habit. Every time I went to the gym, I’d listen to an episode of “The Concrete Gang,” a CFMEU radio show that’s been running since the BLF days. Most episodes begin with a bleak and lengthy list of upcoming funerals for CFMEU members: “Apparently the boys are gonna be having a drink to celebrate his life…they found him yesterday…laying dead for two weeks…condolences to the family and all that.” They also have a segment called “Scallywag of the Week,” where the hosts call out people who are making trouble for the union, be they dodgy developers or irritating pollies. Last week, they nominated Jacqui Lambie, Pauline Hanson, the Master Builders Association, the Civil Contractors Federation, the “sookie-la-la” Small Business Council, Peter Dutton, Vic Roads, the banks, and Murray Watt.

“Who?” one of the hosts asked.

“Murray Watt, industrial relations Minister for Labour.”

“Well, there ya go.”

“Saddling up with Michaelia Cash.”

“Doesn’t she hate us!”

“She’s like Thatcher.”

“Ohhh mate.”

All groaned.

Aside from my parasocial encounters with The Concrete Gang, I found two other sources of information on the CFMEU. Luka and Adam are seasoned construction workers and members of the union. At the moment, Luka works mostly on residential projects. Adam has worked on many different sites, including a Big Build job. I talked to them separately, over the phone. Luka and Adam came to me via different channels, but I quickly realised that they shared similar politics and values. They had both been part of a CFMEU for Palestine working group, which organised to get motions up around Palestine—for instance, that workers have informed choice about whether any of their jobs or materials had ties to the Israeli government. Tom, my cafe confidant, wore a keffiyeh to our meet-up. When he shuffled his papers during the interview, I saw the communist-kitsch typeface of a publication and website called Solidarity; it was a print-out of one of several articles he had written for them. Yes. It turned out that some of my union sources were bonafide radical leftists (paging Andrew Bolt!). Had the reds got under the bedrock?

The truth is more banal. When you do any kind of workplace organising, you realise you’re working with people of many different factions and political persuasions: communists, socialists, and Trotskyists, sure, but also ALP members, anarchists, liberal humanists, apolitical bureaucrats, social conservatives, Liberal voters, and, even, sometimes, self-professed capo dogs. Many CFMEU members fall into the non-leftie categories. They’re in it for the OHS standards and the better-than-average pay rises—and who could blame them? Luka and Adam want these, too, but they also have strong opinions about the direction the union should take. When I asked them some probing questions about the gap between what they want and how the union currently operates, they spoke the way you’d speak about a beloved but slightly troublesome brother. They were protective, but critical and clear-eyed about the shortcomings. That seemed reasonable to me: as members, they stand to lose a lot if the union goes under, and only family is allowed to talk shit about family.

They each readily volunteered, for instance, that there is machismo in the CFMEU. A lot of this has to do with Setka. In the eyes of the public, Setka’s bad behaviour is synonymous with the culture of the union; and the longer he remained in power, the more difficult it became to distinguish the two.

Luka said that although Setka was excellent on worker safety, he should have stepped down when the allegations of abuse against his ex-wife first aired in 2019. But the Women’s Caucus of the CFMEU is strong and well-respected, he told me, and there are staunch current and former women staff like Lisa Zanatta and Sue Bull. Adam mentioned that the CFMEU had got provisions in EBAs ensuring things like women’s toilets and parental leave. “But the Setka thing kind of overshadows all that,” he said. “It’s hard to reconcile that we’re doing all these things for women, but then we’re not going to do anything about this man that abused his wife.”

Both men think there could be some truth to the “Building Bad” allegations, but don’t know to what extent, and vehemently oppose the appointment of an external administrator. They want the process to be handled internally. Luka was pleased that the union had hired an independent investigator, and pleased that it was Geoffrey Watson. Watson has form; he’s investigated Liberal Party corruption and property developer bribes, and has a steely reputation. Luka didn’t think the CFMEU would have gone with Watson if they didn’t genuinely want to clean house.

Adam would also like to see the union become more democratic. He talked about a young activist group in the CFMEU, which was started by a shop steward, but then got taken over by officials. “Now, everything that happens in that meeting is already determined by the officials.” And in the branch meetings, though members vote on matters, the votes are non-binding and can be overruled by management. “They’re visually more democratic than other unions, but it’s stage-managed,” he said.

On the other hand, Luka pointed out that democracy doesn’t just happen at branch meetings, but on union job sites. In the mornings, they have “toolbox meetings” where workers can raise any safety issues with the shop steward or delegate to follow up. Toolbox meetings happen at non-union sites too, but whether your concerns will be heard is another matter. “The quickest I’ve ever been sacked was two-and-a-half days,” said Adam. He said it was for pointing out an issue with a hoist on a non-EBA job.

*

By the end of these conversations, I had a better understanding of what was at stake for the CFMEU and its members: basically, the entire functioning of the union’s day-to-day operations, the state of its mainstream public reputation, and the future of its place in the construction industry—so, quite a lot. But I still had questions. What do the women of the CFMEU think of Setka and their union’s culture? Is the members’ vision for post-Setka democratic bliss a pipe-dream or a possible reality? What does the legislation mean for other unions, and for the union movement as a whole? My investigation was not over; the hard hat would remain in place for awhile yet.

More immediately, I wondered what was going on behind the scenes at the union, in the offices, backyard BBQs, and break rooms of CFMEU officials and members. I did have some insight into break-room machinations, at least. A couple of weeks ago, one of my sources texted me a photograph of a poster that went up in union spaces when the allegations first broke. Sans-serif font on a white background politely requested stories, via QR code, of the good CFMEU had done for their members, to be sent to the Fair Work Commission. Frankly, it looked more HR than CFMEU. Tom scoffed when he showed it to me—corporate bureaucracy. But, more recently, a new poster went up in the break rooms, perhaps indicating an escalation in tactics. It used a smudgy, true-crime-ish typewriter font and had a ripped-paper effect on the edges. A glaring red headline proclaimed: “FAKE NEWS!” A short, sharp message read: “...corporate Australia use the media to attack YOUR union, YOUR rdos, YOUR wages and conditions.” It ended: “BE READY TO FIGHT LIKE HELL.”